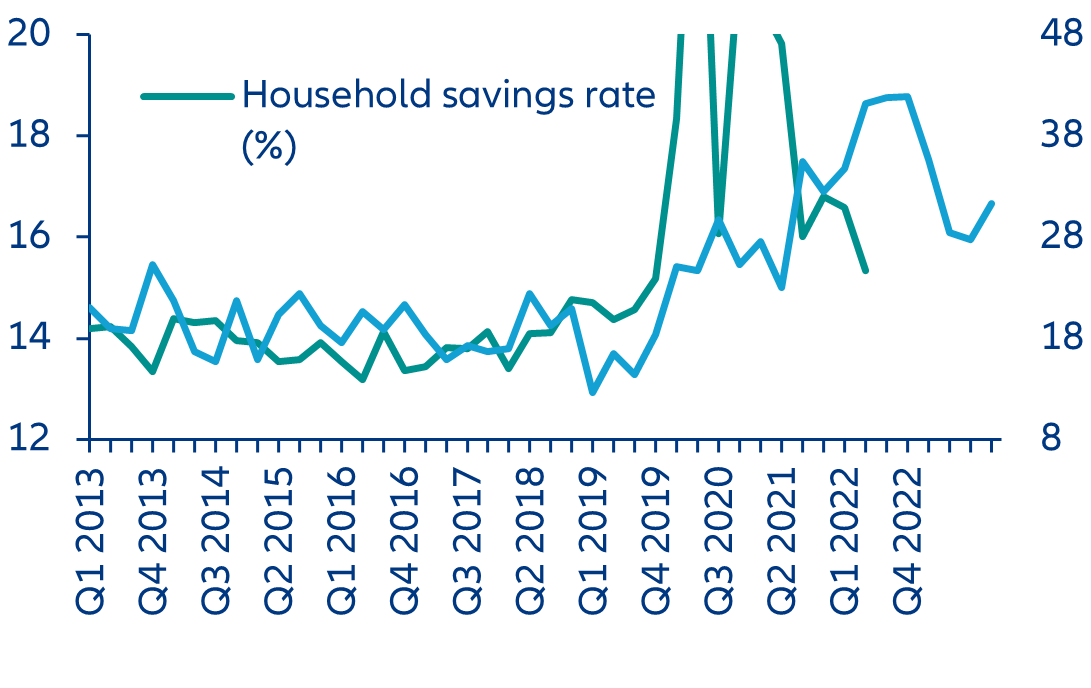

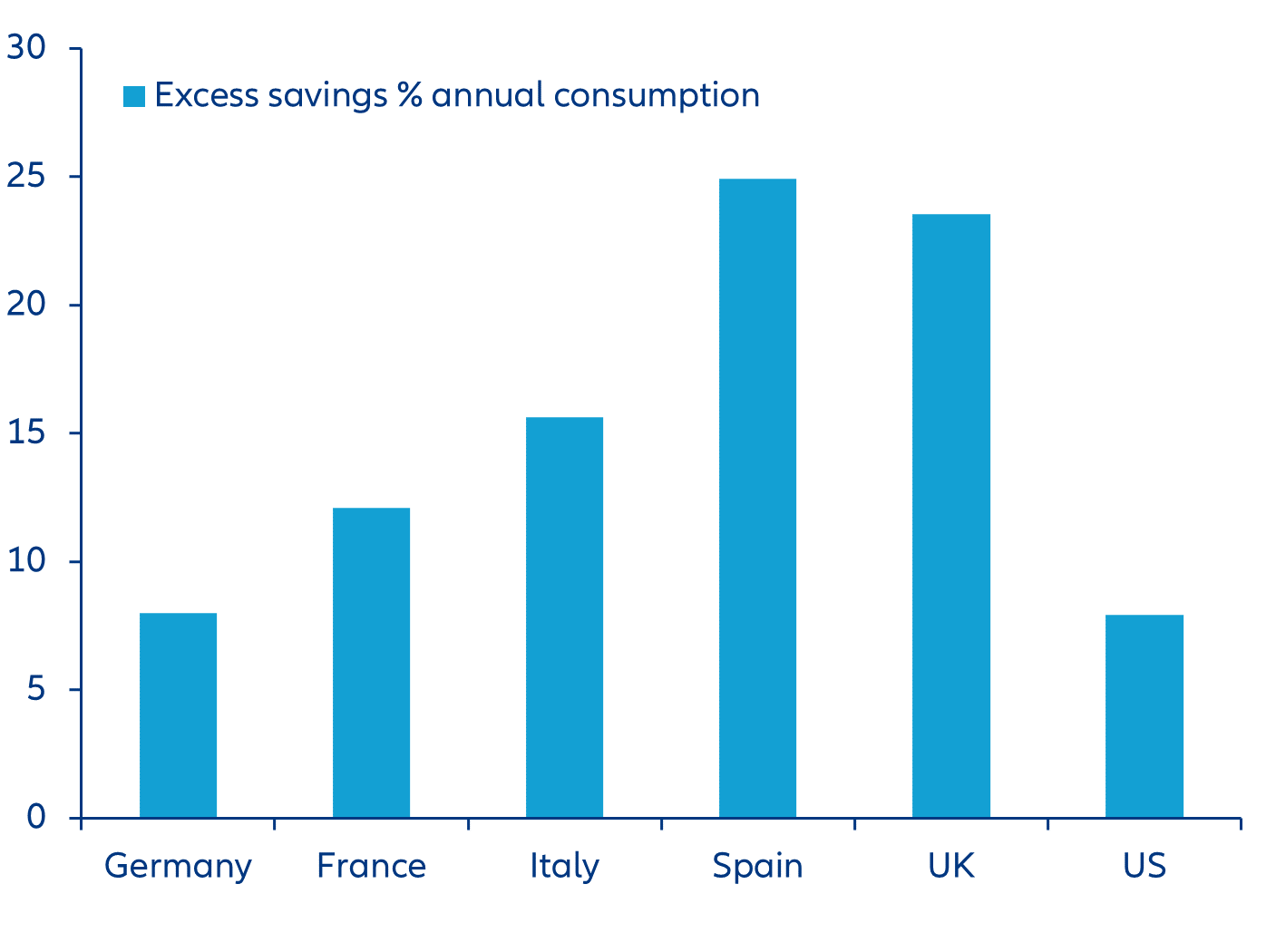

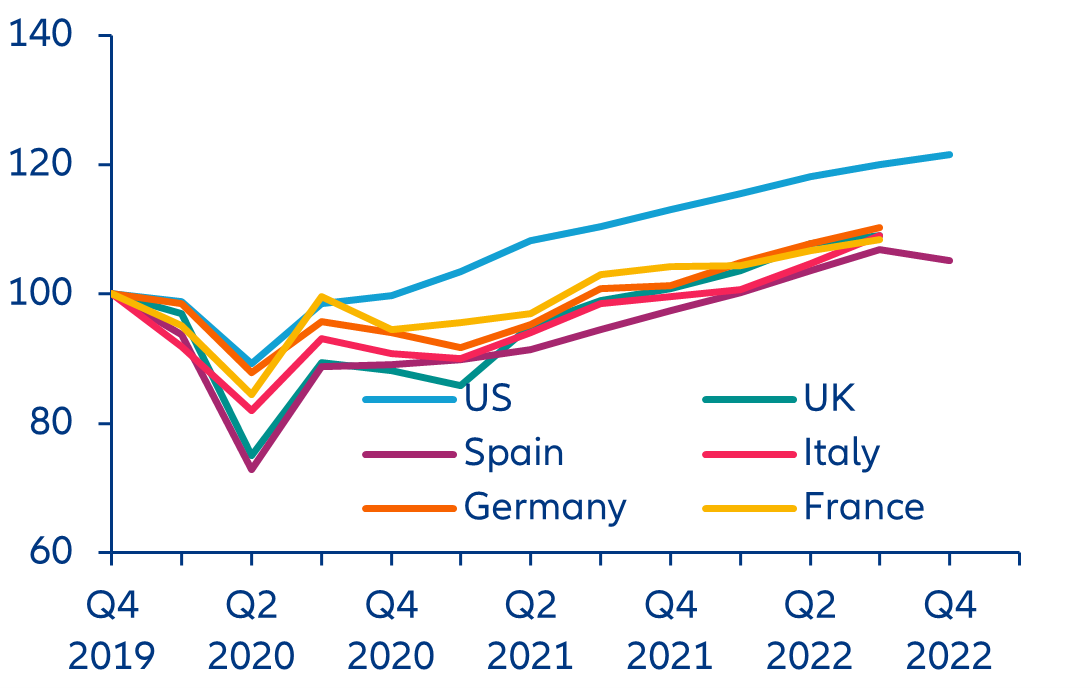

- Households’ pandemic savings are still large in both Europe and the US. These excess savings relative to consumption are largest in the UK and Spain at around 20-25%. In the US and Germany, however, they stand at less than 8%.

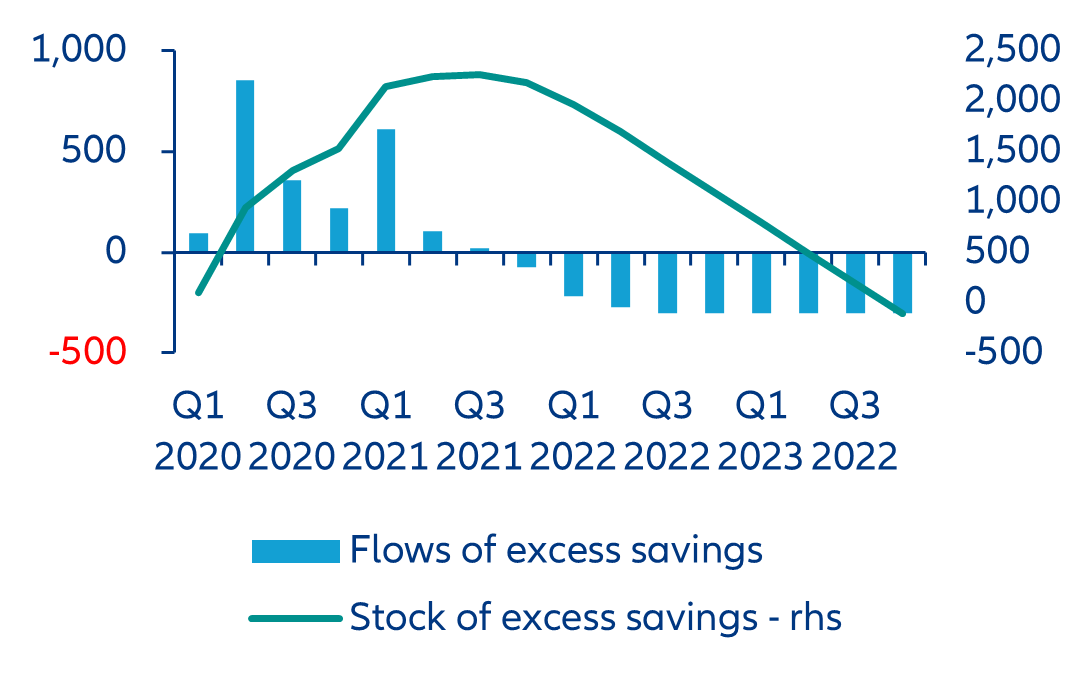

- The US stock of excess savings has been depleting fast with the reopening and the inflation surge: these savings could be fully depleted after the summer this year.

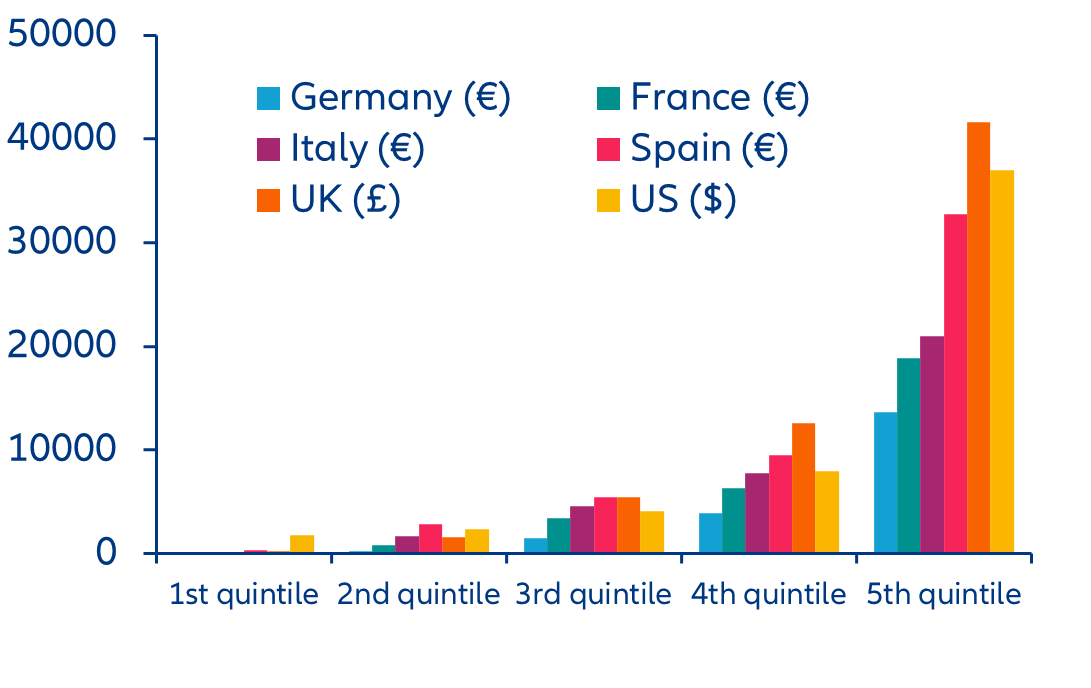

- In Europe, excess savings have not been spent as much as in the US, mostly because of the uneven distribution (the bottom 40% of households has virtually no excess savings while the top 20% has some form of extra savings between EUR14,000 in Germany and EUR33,000 in Spain) but also because they are mostly held in illiquid assets such as real estate.

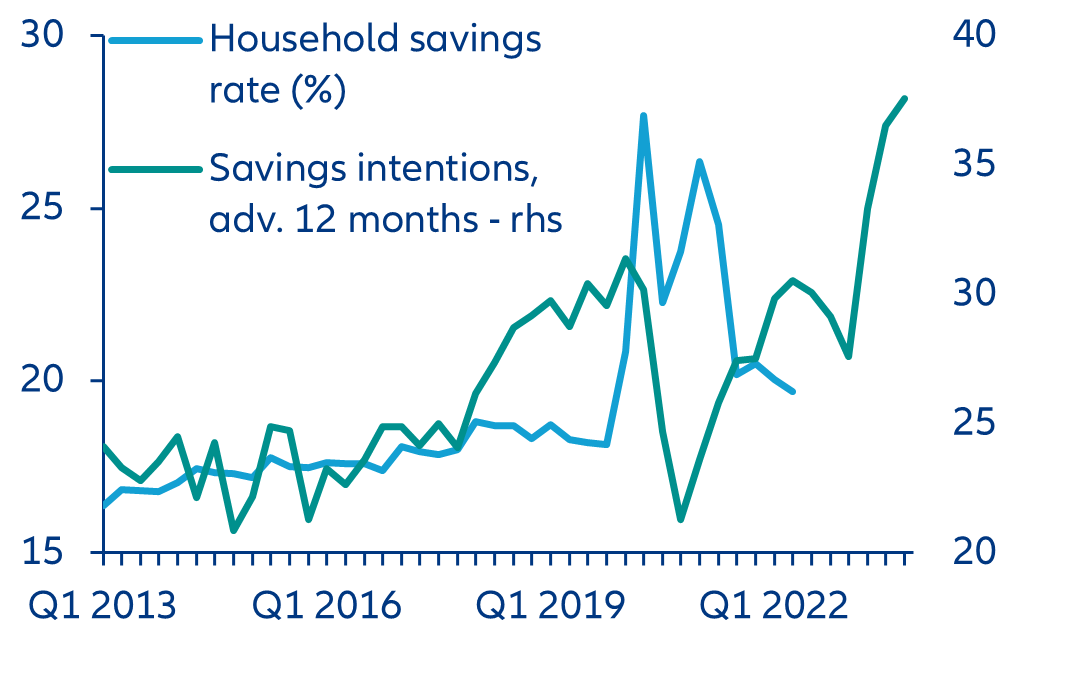

- Recession fears, sticky high prices, and rising interest rates – as well as social protection reforms – mean that savings intentions are elevated in Europe, and even rising in Germany. Consumer spending will be the weak link in 2023.

FEATURE:

Americans to fall off the pandemic savings cliff after the summer break, while Europeans hoard even more

What to watch

- ECB day — not done yet

- Eurozone — a recession avoidance syndrome

- India — budget announcement in the midst of a financial crisis

ECB day—not done yet

Persistently high inflation for most of the year will keep the ECB on a hawkish path. As expected, the Governing Council (GC) hikes the policy rates again by another 50bps, which has been widely anticipated. Even though Eurozone headline inflation for January dropped more than expected to 8.6% (down from 9.2% in December), the continued strength of underlying price pressures will encourage the ECB to maintain a restrictive monetary stance until the end of the year against the background of a resilient labor market and persistent wage pressures.

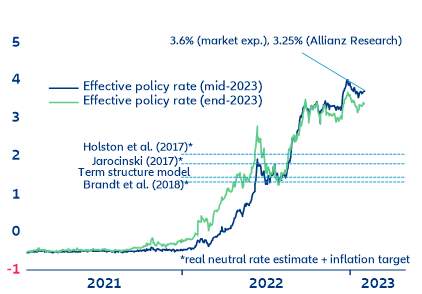

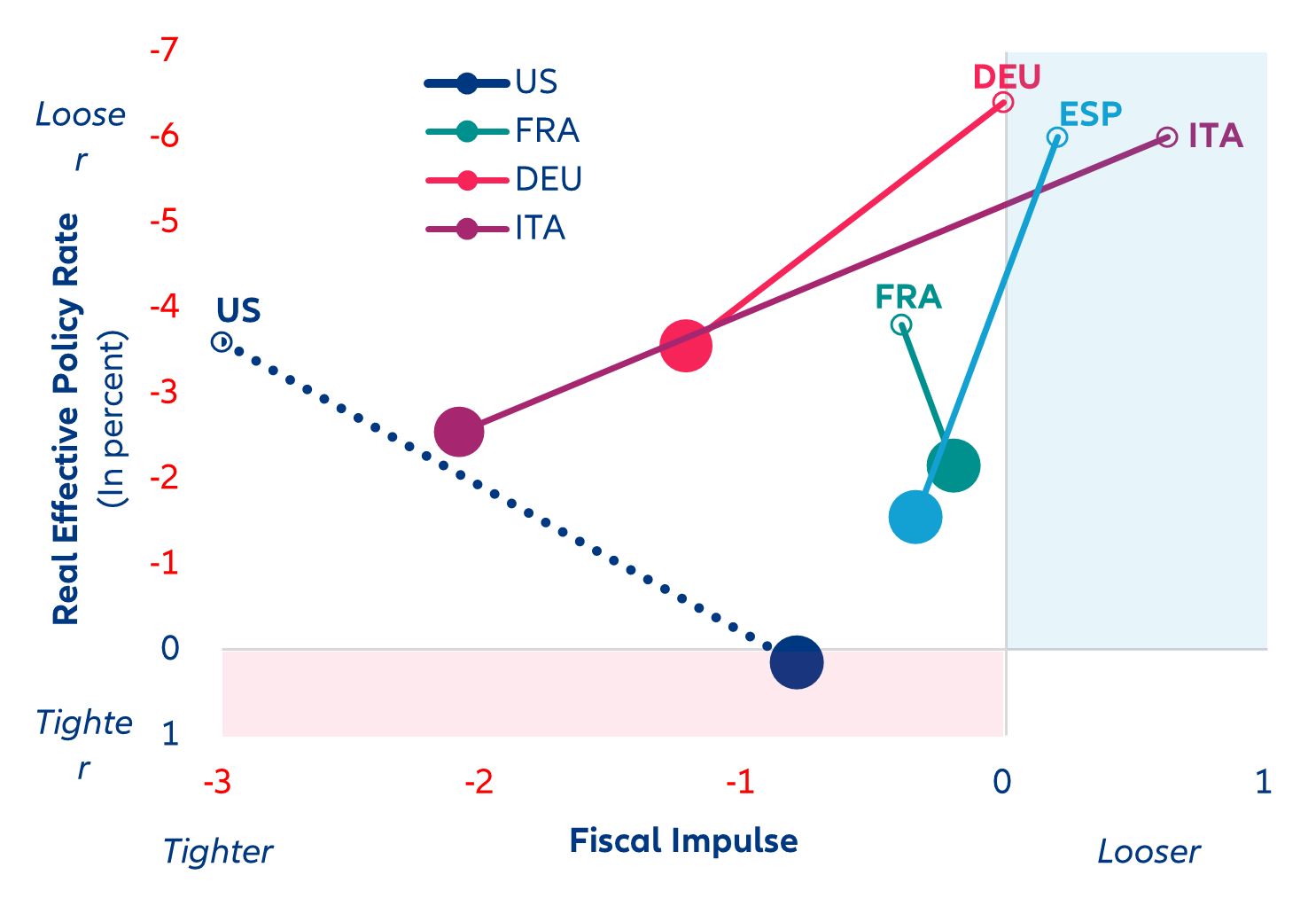

Going forward, the ECB’s challenge will be to restore forward guidance on the path of policy rates for the remainder of the year as inflation seems to have peaked. For the moment, the GC decided to pre-commit to another 50bps-hike at the next policy meeting in March. While recent communication from several GC members suggests that multiple 50bps-hikes are possible in the coming meetings, the minutes of the last GC meeting in December also underscored that the data dependency of the future rate path remains a key consideration. Since the last ECB forecast does not provide ground for changing the current data-driven forward guidance, we expect the ECB to slow the pace of rate hikes to reach a terminal rate of 3.25% for the effective policy rate (deposit rate) until May 2023 (Figure 1). Slowing growth and rising unemployment will mitigate wage-price pressures as supply-demand imbalances gradually subside. Given the expected stickiness of core inflation (especially for non-energy goods, which reached a record of nearly 7% y/y), the ECB will delay potential interest rate cuts to 2024.

Eurozone—fiscal steering away from the recession?

Earlier this year European leaders were quick to trumpet that there will be no recession, but the growth outlook is very much influenced by the scale of fiscal support. Governments have underwritten an increasingly expensive fiscal put option on real activity. Households and firms have simply become accustomed to being protected against the adverse impact of economic shocks, especially if they are (at least in part) induced by policy choices that have raised the cost of living and production — whether these are containment measures (constraining supply chains) or sanctions on energy imports from Russia (raising gas and oil prices). As corporate margins compress and real household incomes deteriorate, most of the current measures have been extended into Q1 2023 for a total of more than 3% of GDP on average, which is about half the size of the Covid-19 packages. With the energy crisis – and in turn the inflation hit to the private sector – not yet past the peak, we expect EU governments to delay meaningful fiscal adjustment to next year.

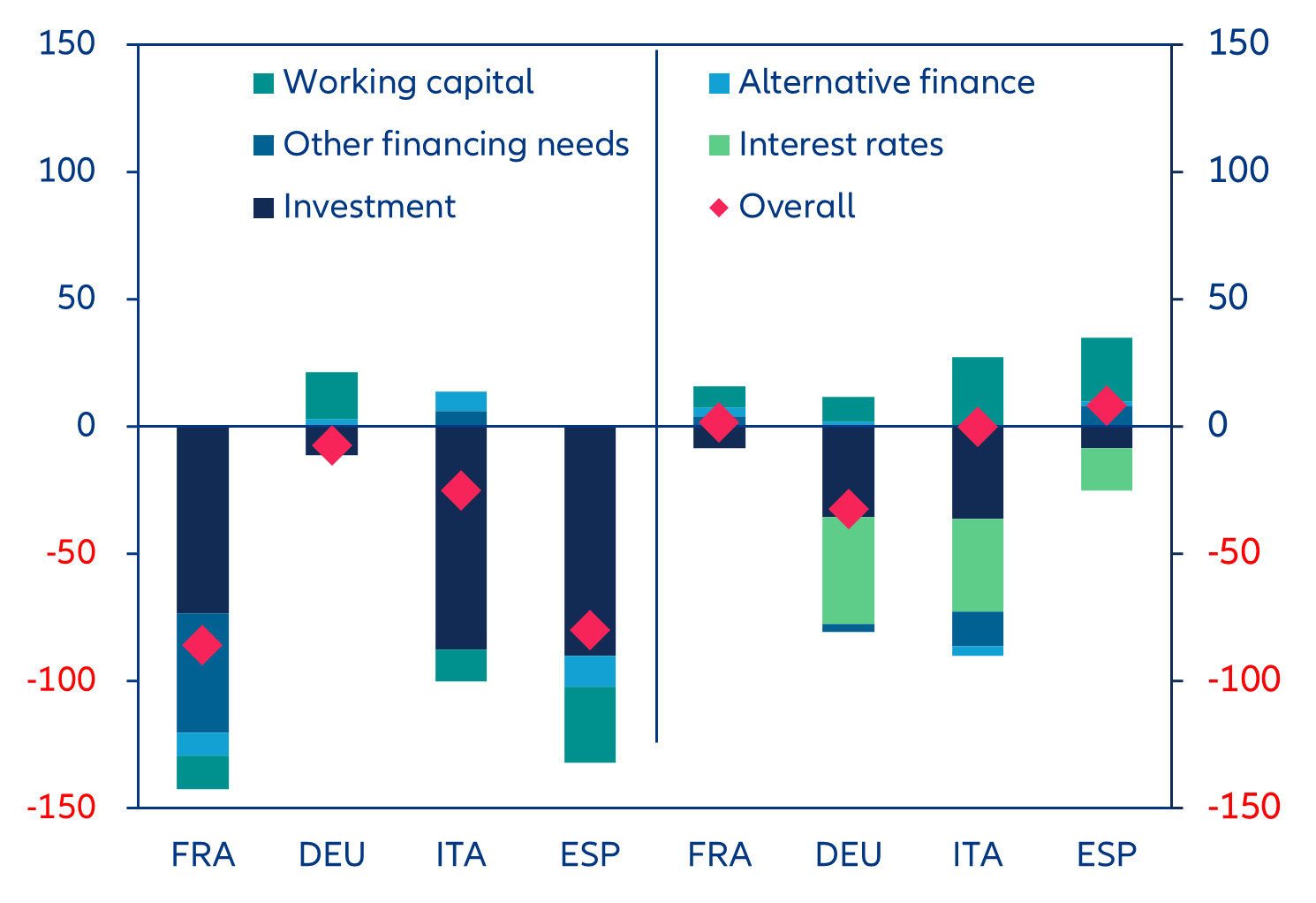

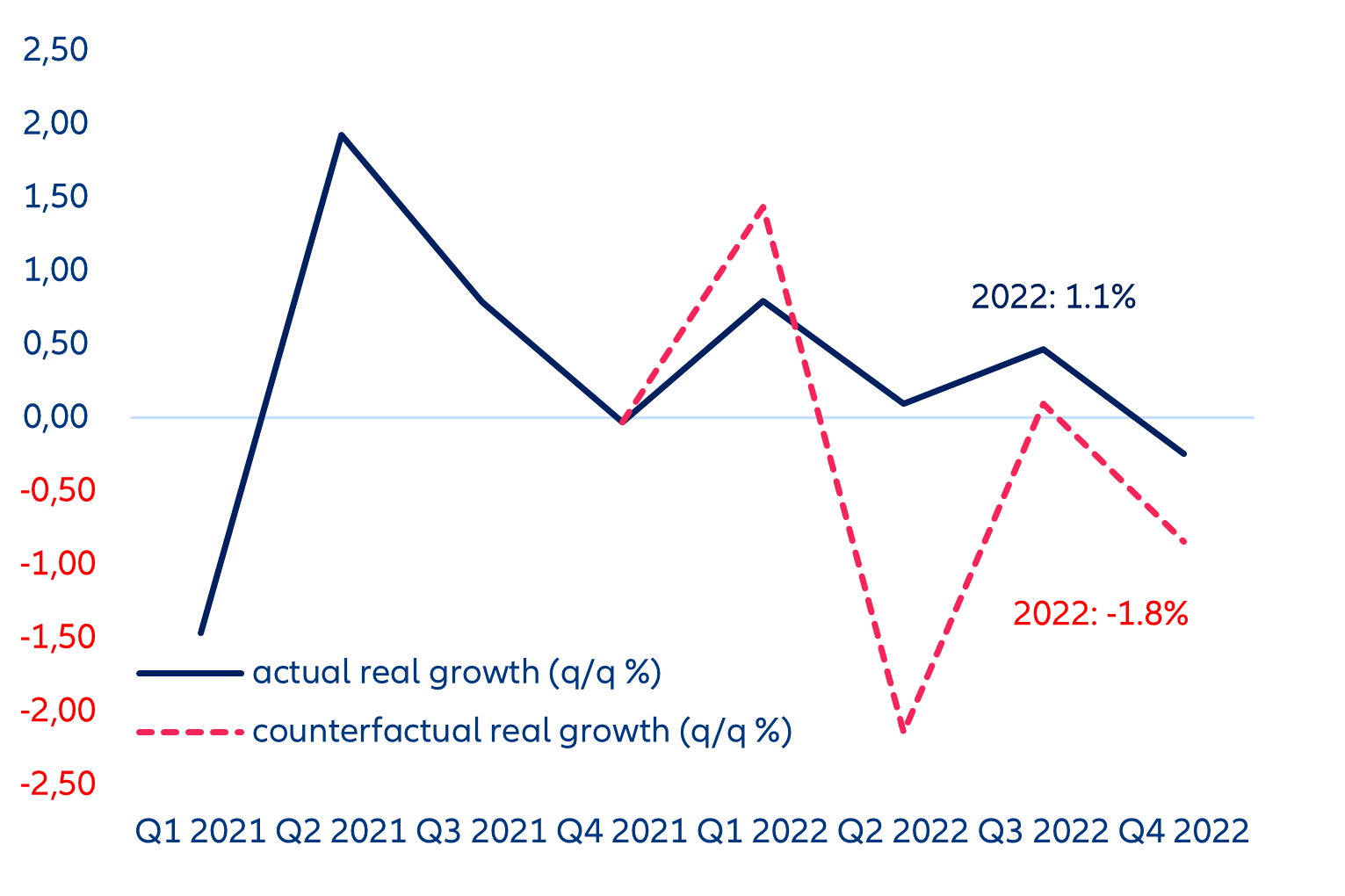

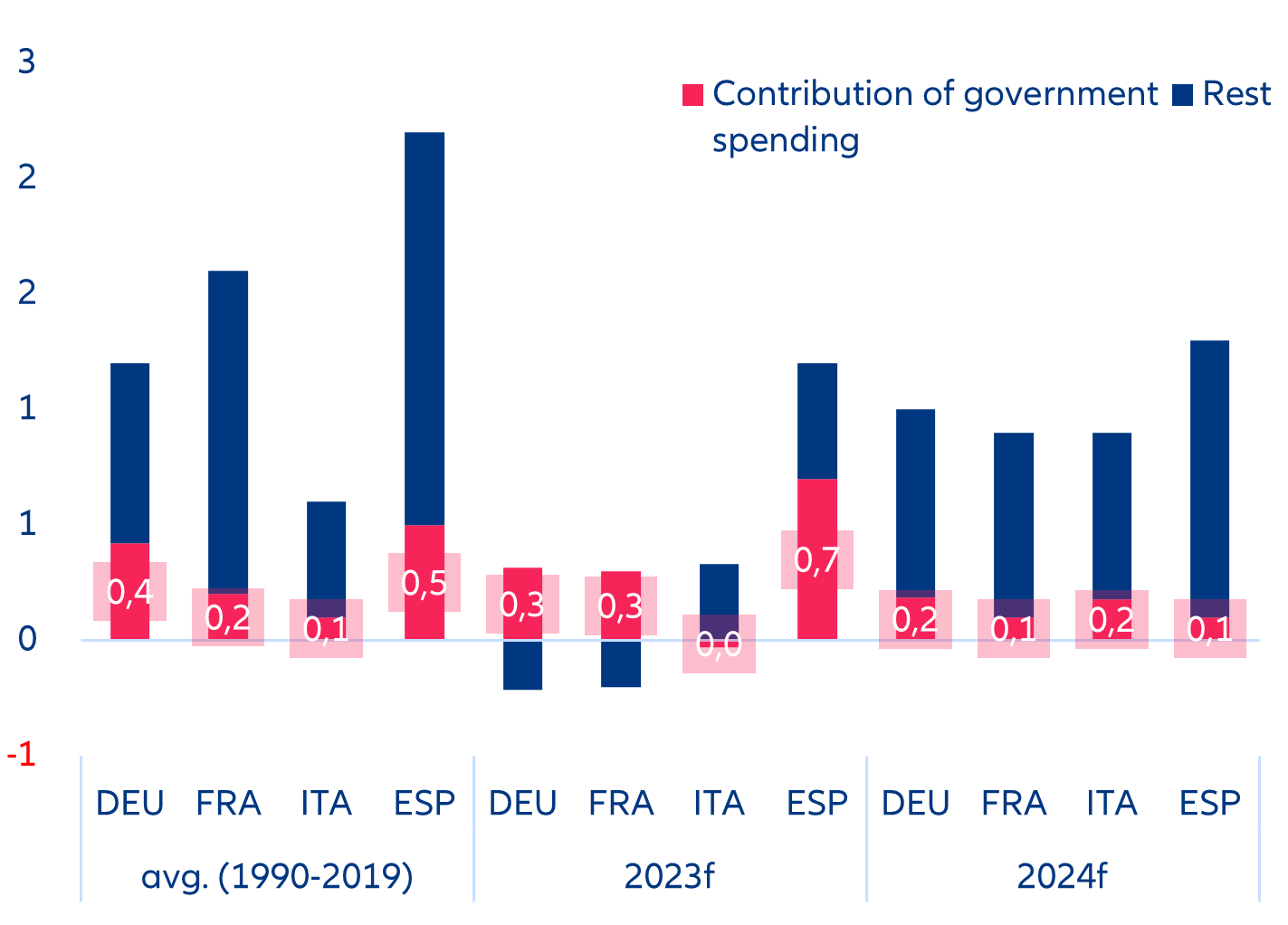

Last year, in Germany, government spending lifted growth by 2.9pps from -1.8% to 1.1% after considering the second-order impacts on consumption and investment. Going forward, for the four largest Eurozone economies, we estimate that government spending will contribute up to 40% to growth on average over the next two years – which is significantly above the long-term average of 22% (Figures 3 and 4). While available fiscal support will soften the blow on demand, it can only partially compensate for the impact of the energy crisis. Consumption and investment plummeted during Q4 2022, suggesting that still-low business confidence and consumer sentiment are likely to delay the rotation back to private demand. Overall growth remains weak and it will be difficult for most countries to close the output gap over the near term. We still expect most of the large Eurozone economies to slip into recession during the first half of this year, followed by a shallow recovery next year (+1.1%).

Rising interest rates will, however, reduce fiscal space for continued support. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine last year, fiscal policy has switched from post-Covid consolidation to new support in response to the energy crisis. However, the big fiscal leaps are behind us as the room for maneuver is much more constrained. The fiscal impulse will be marginally negative as governments narrow their cyclically adjusted deficits this year, driven to a large degree by Germany and Italy (Figure 5).

Fiscal support measures at the national level should not fuel EU divergence, including by distorting intra-European competition. This also extends to designing and funding the EU’s Green Deal Industrial Plan as an effective response to the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), including by shifting the focus towards scaling-up investment in transforming the energy sector to safeguard sustainable growth. The current plan already includes important elements, such as the creation of a “European Sovereignty Fund” to support fiscally-constrained member states and leveraging EUR26.2bn in risk capital from InvestEU to generate EUR372bn of private investment (in addition to EU funding for energy projects as part of a topped-up RepowerEU (EUR270bn)). However, the additionality of the earmarked funding remains small compared to the potential size of the IRA (after accounting for the tax credits-induced private investment increase), which could reach up to USD1.7trn according to recent estimates.

India’s budget announcement in times of financial turmoil

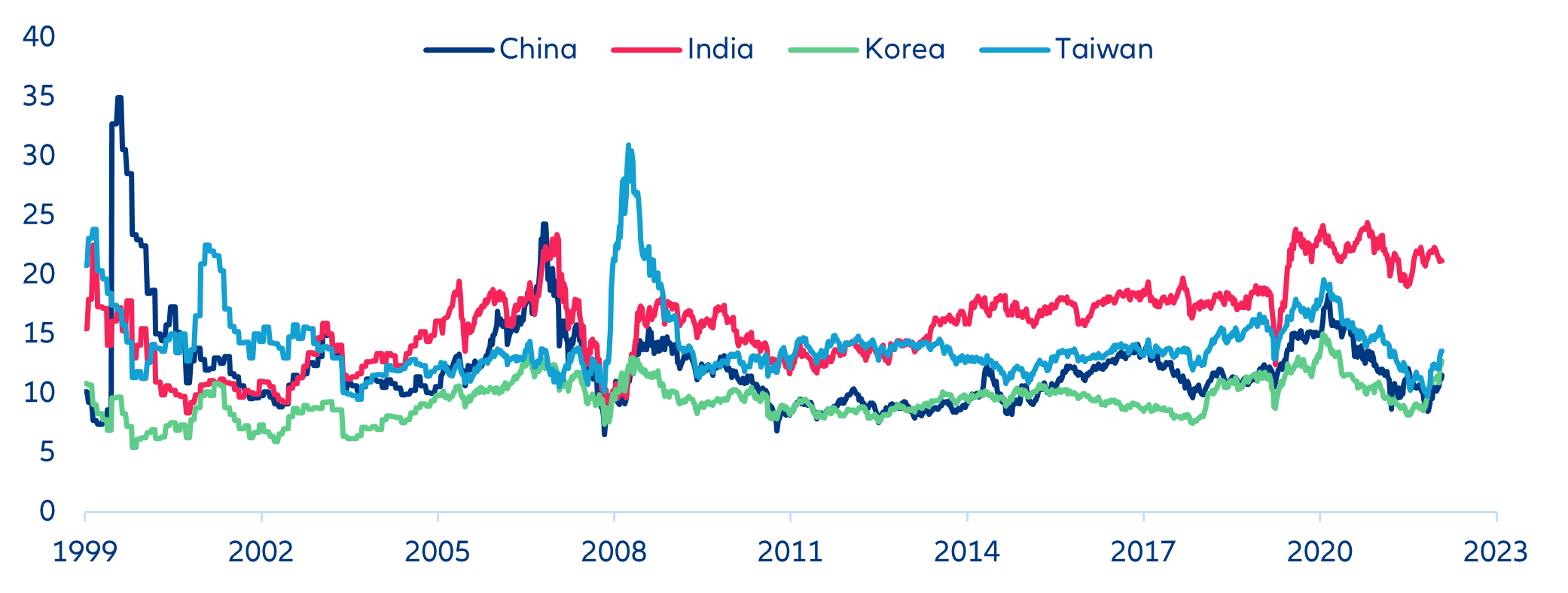

The turmoil around one of India’s largest conglomerates has shaken country’s financial markets, and it is a reminder of the need for structural reforms. Indian equity markets proved resilient against the severe global correction in 2022 – in part thanks to the country’s different exposure to the China-US tensions compared to other regional competitors for financial flows. This has in fact lead to an overvaluation of its assets vs. that of other emerging markets, but the turmoil around the conglomerate threatens to reverse this. As such, the challenges that the Indian financial markets face are multiple: increased scrutiny over the country’s capacity to orderly absorb large flows, the stress test to the financial system should liquidity problems arise, comparatively expensive ratios (Figure 6) and the downward pressures coming from the macroeconomic outlook.

The correction will only get worse. While the initial market sell-off (more than 20% in the affected stocks and around 3% in the broad market) seems to have halted, there is more to come. Even as Indian conglomerates are almost guaranteed financial aid, given their strategic role in the economy, Indian financial authorities are likely to tighten their grip to tackle the unwanted consequences of the expansion and increasing complexity of the financial market. Investors will also reassess their investments in the country. According to our calculations, markets could fall another -8% this year as expectations adjust to the long-term trend. But inaction could bring even harsher consequences: If authorities ignore the challenges that the internationalization of financial markets brings, the potential damage in the medium term will be larger.

The recently released Union Budget could help cushion the cyclical downward pressures coming from slowing private consumption and exports; however, India needs further reforms to reach its long-term potential. On 1 February, finance minister Sitharaman presented the budget for fiscal year (FY) 2023-24. Ahead of the upcoming national election in mid-2024, the budget aims for fiscal consolidation while protecting growth and lower-income populations, targeting a deficit of 5.9% of GDP in FY2023-24, down from 6.4% the previous year. It also aims for a large jump in capital spending (+33%), with a continued focus on infrastructure (including the energy transition). Beyond the short-term, higher infrastructure spending should continue to attract foreign investors to India. Policymakers have also put in place incentive measures in recent years (e.g. Make in India, Production Linked Incentive schemes) to develop the country as a manufacturing hub and competitive exporter in the long run. Indeed, India was one of the countries that benefited from the 2018-2021 trade tensions between the US and China and stands to benefit again, especially as China’s population is shrinking. However, further structural reforms are still necessary, including to improve financial stability and the labor market, and to reduce bureaucratic red tape.

In focus - Americans to fall off the pandemic savings cliff after the summer break, while Europeans hoard even more

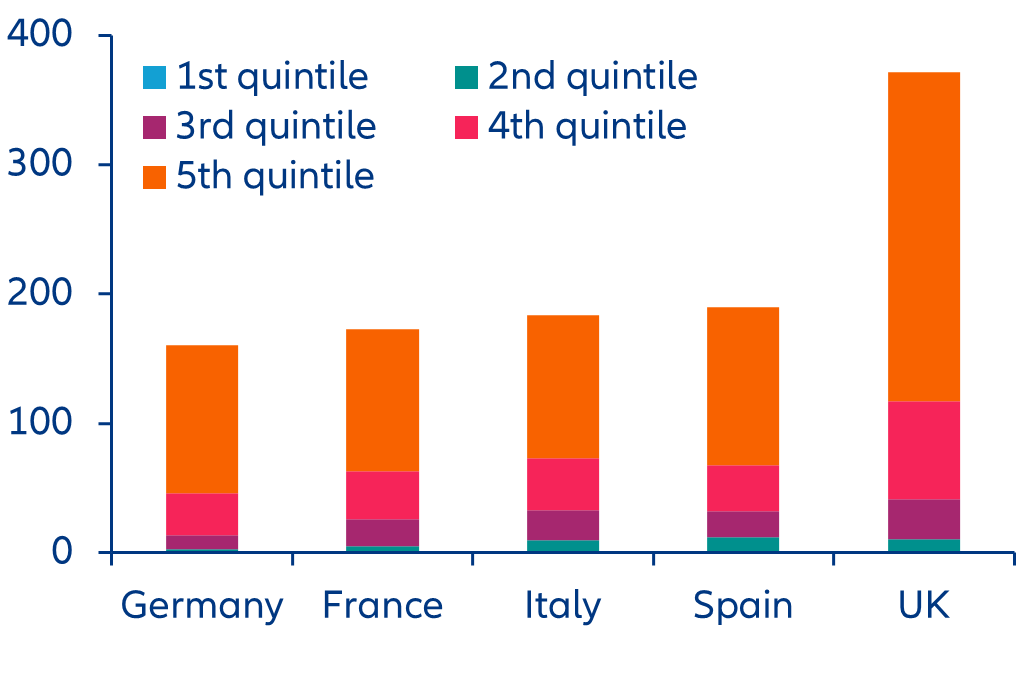

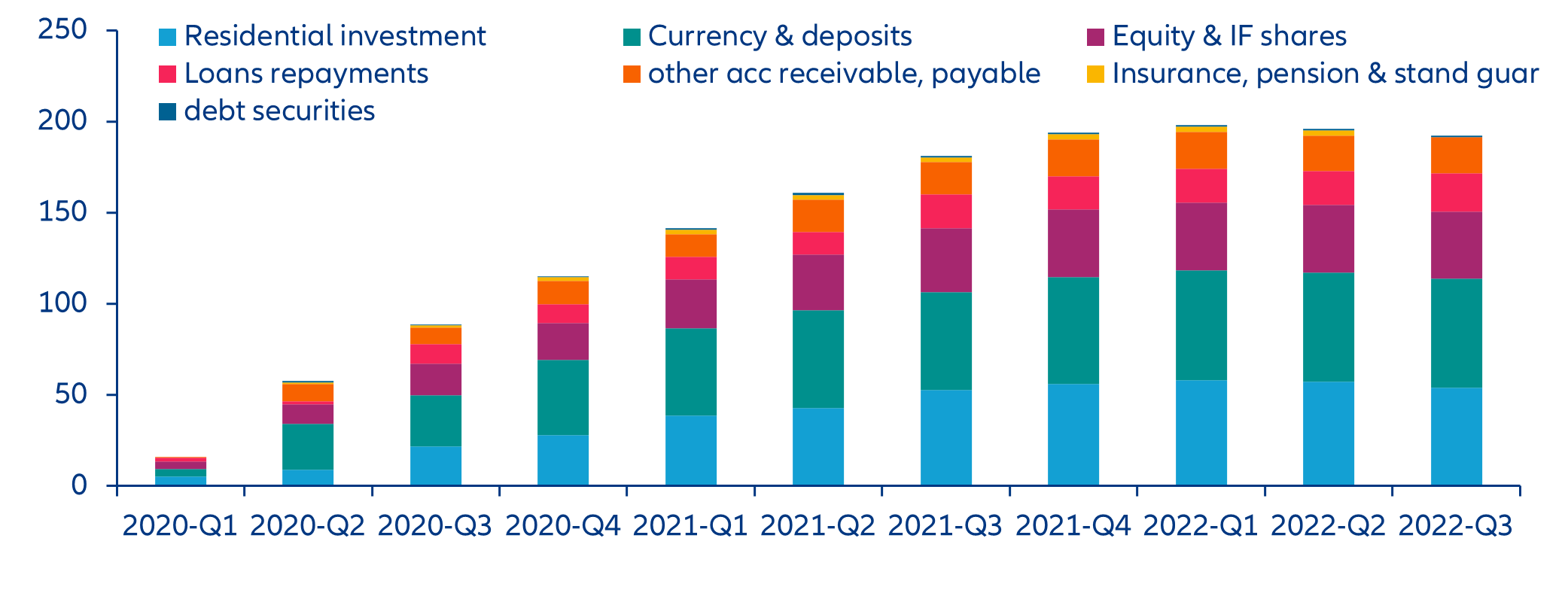

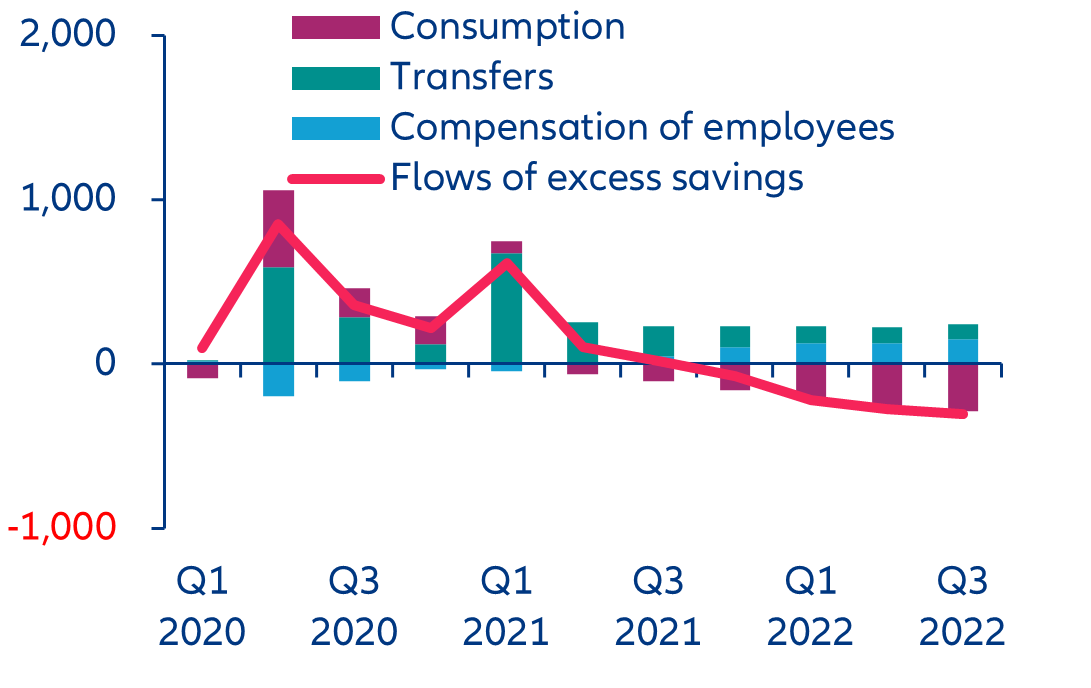

Excess savings from the pandemic are the largest in Spain and the UK. Households accumulated large savings during the pandemic in 2020 as spending options were limited while fiscal transfers boosted their disposable income (especially in the US). Two years later despite the reopening and the inflation surge, the stock of excess savings is still close to 25% of annual consumption in the UK and Spain (i.e. GBP370bn and EUR190bn, respectively; Figure 8). Excess savings were lower as a share of consumption in France and Italy but still large at EUR175bn and EUR185bn, respectively. While strong labor markets have been boosting incomes, households have not generally used this extra income to spend more, especially in the UK and Spain, which explains why they maintain some form of hoarding.

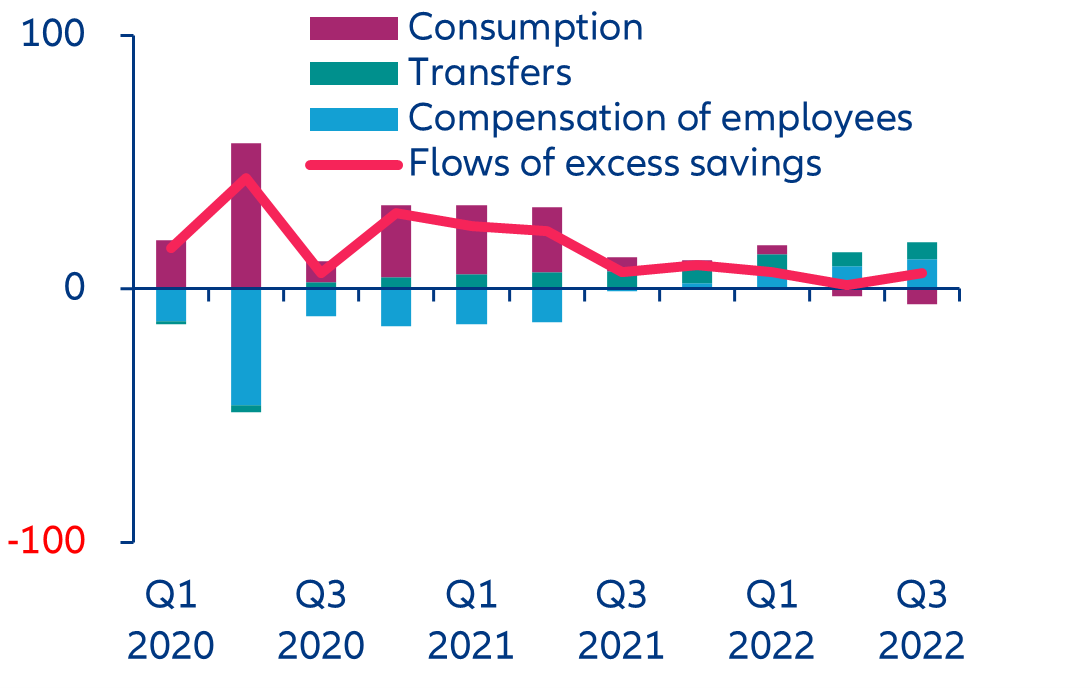

In Europe, despite the sizable excess savings that remain, we do not expect a consumption boost this year, given the uneven distribution among households. We estimate that the bulk of excess savings are in the pockets of higher income households[1] (Figure 10). For instance, in the UK, we find that the 20% of households with the highest income hold GBP250bn of excess savings compared to a meagre GBP1.5bn for the households with the lowest incomes. The average high-income household has excess savings ranging from EUR13,650 in Germany to GBP41,600 in the UK. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the bottom 20% of households have essentially no more excess savings left.

[1] We make the simple assumption that the stock of excess savings is distributed across households in the same proportion as assets. Lower-income households have received higher fiscal transfers during the pandemic but subsequently have been hit the most by elevated inflation. Therefore it is a fair to assume that the stock of excess savings is now largely held by higher-income households by the end of 2022.