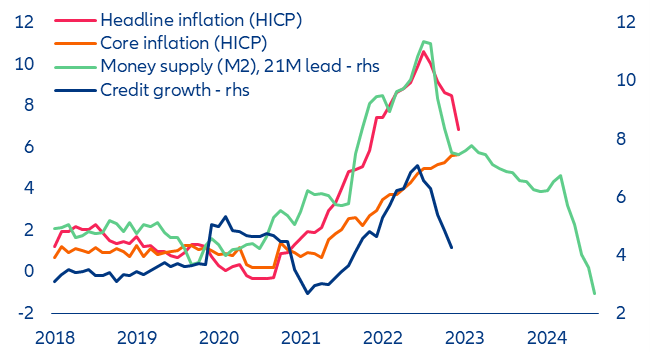

- Ahead of the next round of monetary policy meetings next week, continued banking sector stress raises the question of whether financial stability concerns might alter the policy rate path in the US and the Eurozone, allowing inflation to remain higher for longer. Overall inflation has declined (and more so in the US); however, core inflation is becoming increasingly sticky, especially in the Eurozone where it reached an all-time high of 5.7% y/y in March. Wage pressures increasingly drive higher prices for services. However, the risk of a deflationary shock from bank failures and retrenching credit seems to be getting more serious. As money supply keeps contracting, it is hard to see a relapse of inflation, even though some bumps along the way of normalizing prices cannot be ruled out.

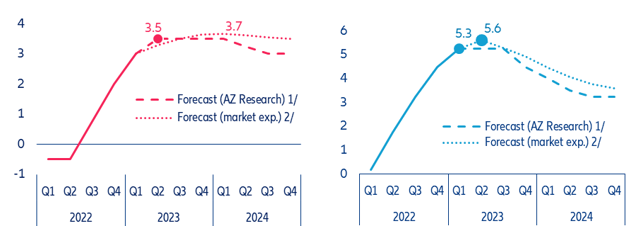

- The steady decline in headline inflation over the last five months (to 6.9% y/y in March) will not be enough for the ECB to abandon its restrictive monetary stance. The continued increase in core inflation will reinforce the ECB Governing Council’s conviction that further rate increases are still needed to prevent (still) strong wage pressures from embedding higher inflation in the economy. We forecast two more 25bps hikes in May and June for a terminal rate of 3.5% (which remains in place until Q2 2024) despite stagnating growth. There is an upside risk of a 50bps hike if the Q1 growth numbers surprise on the upside and spillover risk from the second round of US banking sector stress remains contained.

- The Fed is on track to deliver a 25bps rate hike – the last of this cycle. The unwelcome increase in liquidity – fueled by the banking crisis and the debt ceiling drama – gives the Fed even more reason to keep rates high for the next few months before a pivot later this year (-25bps in November and -50bps in December) to 4.5% from a peak of 5.25%.

In Focus

Policy rate decisions: the end of the beginning or the beginning of the end?

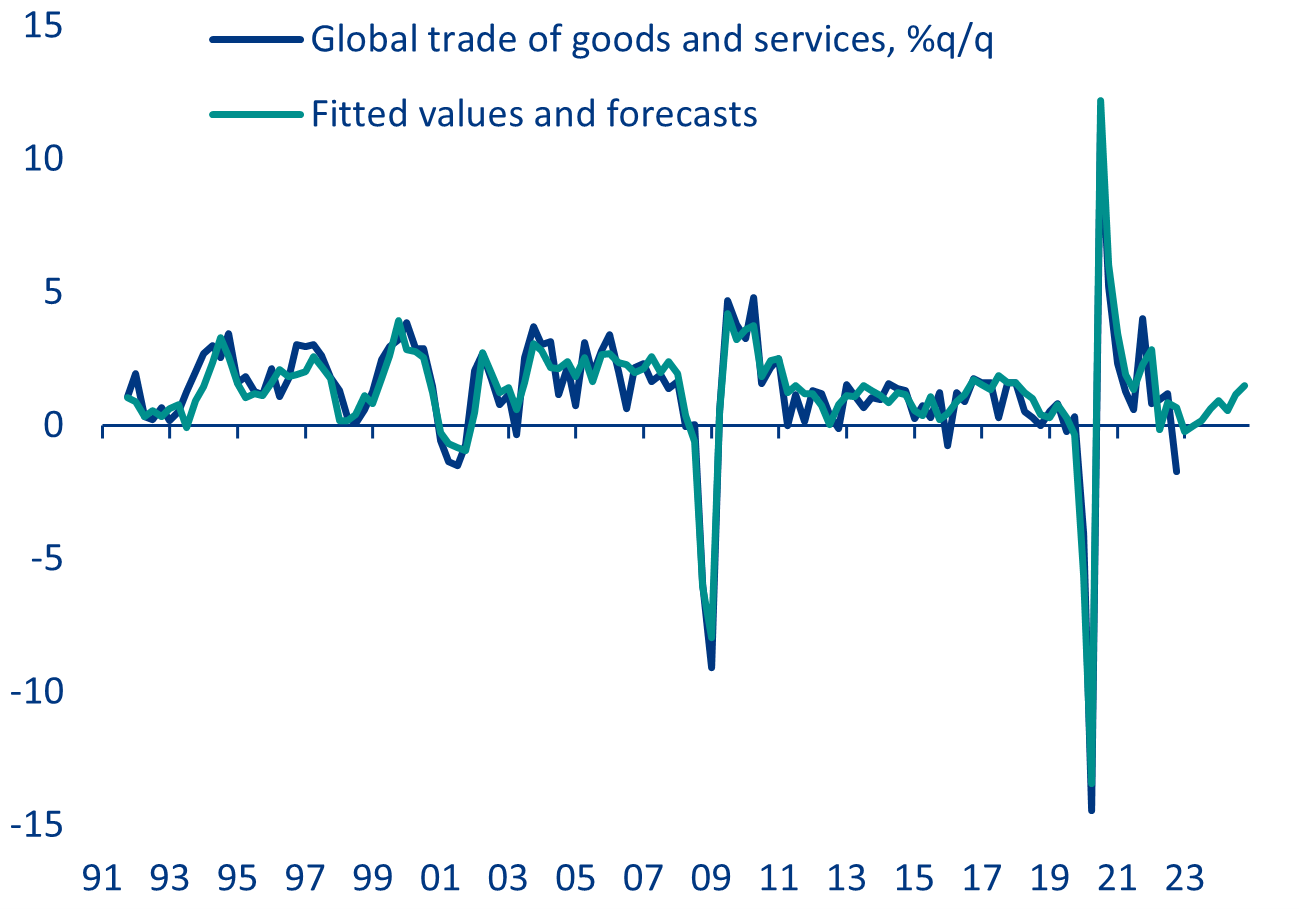

Global trade – A recession followed by a very mild recovery

Electric cars – No price war yet

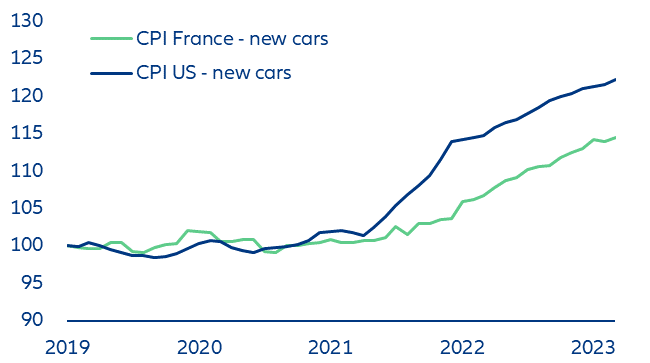

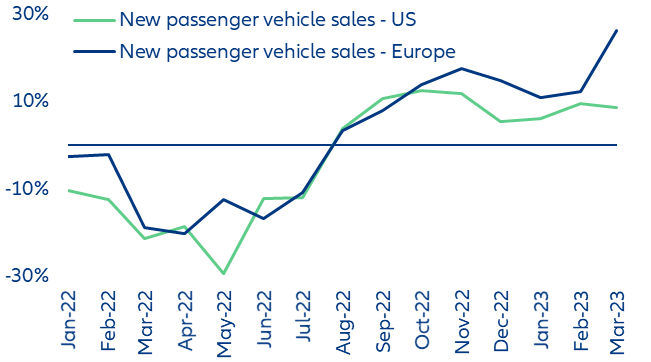

car prices show no sign of cooling down in the US. Tesla, the world’s largest battery-electric vehicle (BEV) manufacturer, announced another round of substantial price cuts in Europe and North America. Last year, rising new and second-hand car prices (up +7% and +11%, respectively) played a major role in driving headline inflation figures, contributing to the record profits reported by dominant carmakers. Tesla’s move, while significant at a micro level, is unlikely to have any substantial impact at a macro level. With about 30,000 cars registered in France in 2022, the company’s market share is rising but remains below 2%. Since January 2023, the two rounds of price cuts have brought the bill for entry-level versions of its Model 3 and Model Y down by -10% and -21%, respectively. Factoring in the company’s market share, sales mix and the announced priced cuts, and keeping all else unchanged, we find that the announced price cuts would bring down the total French new car price index by just -0.3%. Overall, France recorded a +7.3% increase y/y in March 2023. Applying the same process to the US, we find that lower Tesla prices would have a -0.5pp deflationary impact but overall new car prices still rose by +6.6% (Figure 5).

Deep price cuts are a risky gamble for carmakers. Another reason why industry-wide price cuts are unlikely lies in the importance of the residual value of vehicles for private customers: Any drop in price for a given new model has an adverse impact on the resale value of the same models already on the roads, and to some extent on similar models. Past examples of deep vehicle price cuts were met with negative reactions from current customers whose cars immediately lost value, prompting them to think twice before buying from the same brand. The issue is even more critical for specialized car fleet companies since the residual value of their fleet accounts for the bulk of their assets – in this respect, new car price cuts are taking a toll on their balance sheets. It also applies to the majority of carmakers operating in Europe and North America that offer leasing services through their financial services arm, but to a much lesser extent to Tesla, whose sales mix relies more on cash purchases and traditional credit financing.

It’s a question of time for battery-electric vehicle prices to adjust downwards as market penetration increases. Finding the right pace to preserve car value but ensure BEVs are becoming more affordable will be a major challenge for carmakers in the coming years. Looking at China, where BEVs account for more than 20% of the market, we observe that prices are going down at a much faster pace as new models are being introduced. Together with competition, it is companies moving down the learning curve (being more efficient in designing and manufacturing BEVs, thanks to accumulated experience), reaching economies of scale (having lower unit costs as volumes go up) and coming up with innovative technologies (emerging battery chemistries, in particular) that will ensure future price parity between internal combustion engine and electric vehicles.

German household savings – 2022 was worse than the 2008 financial crisis

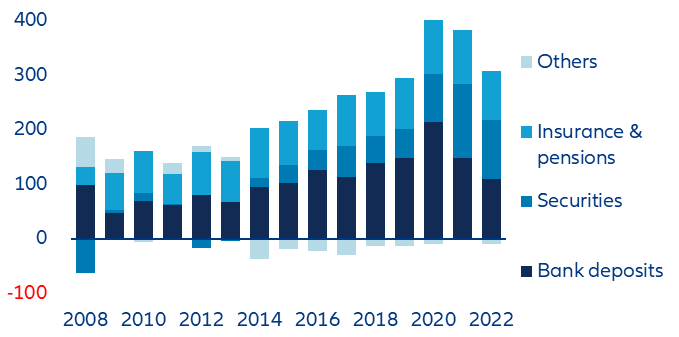

After three years of extraordinarily strong growth (+7.7% on average p.a.), the financial assets of German households decreased by -4.8% to EUR7,462bn in 2022. Good stock-market performance at the end of the year could not compensate for the losses of the first three quarters. In real terms, they declined by a whopping -13.5% in 2022. For comparison, even at the beginning of the global financial crisis in 2008, asset losses were just -4.5%. Moreover, excess savings exist only on paper now; the surge in inflation wiped out all pandemic gains. While nominal values are 10.2% higher than end-2019, financial assets lost 2.1% in value in real terms.

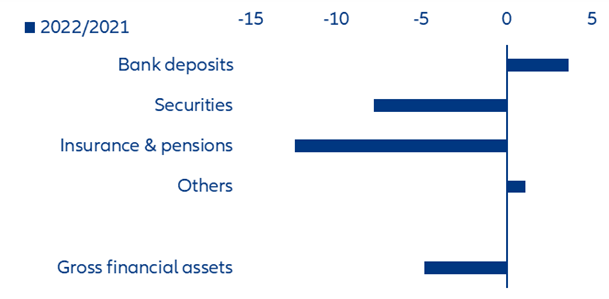

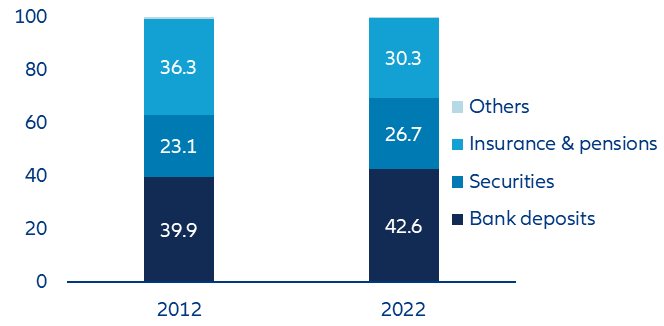

Stocks: The price of the interest-rate turnaround. While assets held in shares clearly felt the effects of the capital market turmoil, debt securities as well as pension and insurance claims suffered particularly from the rising interest rate environment. The losses for securities added up to EUR277.6bn while those of insurance and pension products added up to EUR410.4bn. Year on year, the stocks of assets fell by -7.8% and -12.4%, respectively. Bank deposits, on the other hand, showed robust growth (+3.6%, Figure 7). This asset class is still by far the most popular one in Germany (42.6% of total financial assets), while 30.3% is held in insurance & pension assets and 26.7% in securities (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Asset classes as a percentage of total financial assets, 2012 and 2022

Laziness costs money. The increase in bank deposits to EUR3,183bn was again largely driven by the strong, albeit declining, net inflow of new savings, whereas interest income amounted to only EUR2.7bn, or a measly EUR32 per capita. Nevertheless, the share of bank deposits in the asset portfolio even increased by just under 3pps over the past decade.

At least since last July, there has been light on the horizon again for savers who focus on safety: For new business, the average interest rate on deposits with agreed maturity rose to 1.56% by end of 2022 (against 0.08% by end of 2021), and even climbed to 1.98% by February of this year according to the latest available figures. However, German households do not only seem to have a great preference for safety when it comes to investing money; they also seem to be anything but quick to switch to more attractive offers. By the end of 2022, they still held more than two-thirds of their bank deposits in non-interest-bearing overnight deposits; since the interest rate turnaround last July, they have shifted an average of only about 1% of their overnight deposits per month to the more attractive deposits with agreed maturity. This shift generated an interest income of EUR176mn (August to February). In doing so, they missed out on a whopping EUR2.6bn in extra interest income (if the share reduced from two-thirds to 50% held in non-interest-bearing deposits).

Historically low return on assets. In 2022, the poor performance of households’ financial assets as well as shrinking investment income led to a historically weak result in the return on assets achieved. The nominal implicit return – referring to the total sum of gains (and losses) in value and investment income in relation to the asset portfolio – fell to -7.8% and thus was even significantly lower than that recorded in 2008 (-4.0%). While at least the insurance and pension asset class achieved a positive return in 2008, the combination of negative stock-market developments and rising interest rates led to this historically weak result in 2022.

Tighter financing conditions slow down debt growth. The interest-rate turnaround also had an impact on private households’ debt growth. While the weighted average interest rate on all outstanding loans of German households even declined slightly compared to the previous year – as old loans with high interest rates matured – it climbed rapidly from 1.38% to 3.63% in the same period when looking at new business. Due to these tighter financing conditions, debt growth decelerated versus 2021, namely to +4.5% (2021: +5.2%). However, it still remained well above its long-term average (+3.0%). Debt per capita increased to EUR25,890, whereas the debt-to-GDP ratio fell to 55.7% because of the stronger nominal increase in economic output. Finally, net financial assets slumped by a historic -8.1% during last year (-6.4% in 2008); in per capita terms, German savers owned EUR63,760 (net).

German FDI in Africa – Untapped potential for the green transition and critical materials

With its rich supply of minerals such as cobalt, copper and lithium and its geographic proximity, Africa is well positioned to become a critical partner in Europe’s green transition. The EU Green Deal could deepen Africa-EU cooperation, particularly with respect to renewable energy and the critical materials required for electric vehicles, solar panels and wind turbines. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), for example, produces more than 70% of the world's cobalt, while Guinea is a key source of bauxite to make aluminum and Zambia is the world's sixth-largest copper producer. There is also significant potential for the EU and Africa to work together to generate the green hydrogen needed for scaling up electric mobility and renewable-energy generation and storage technologies.

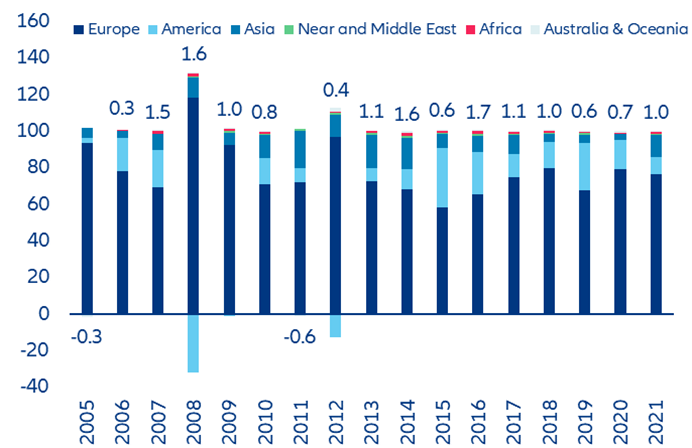

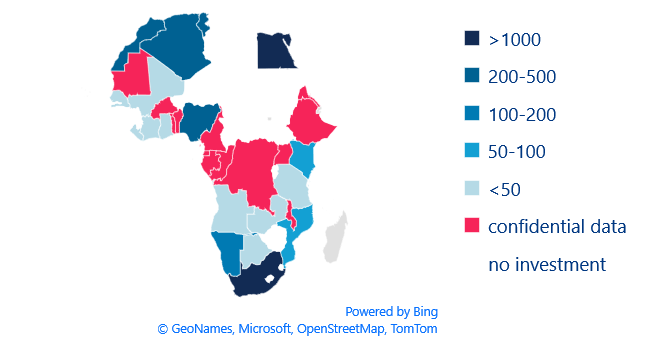

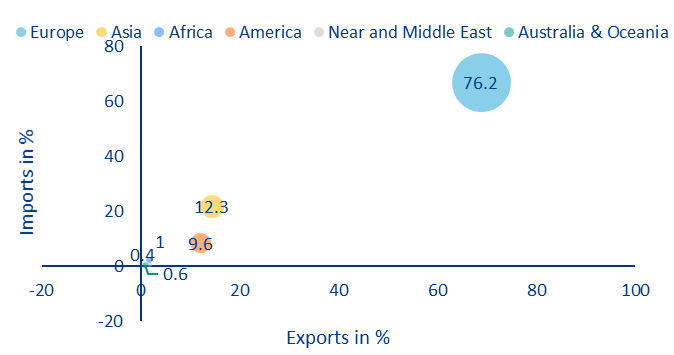

But Germany is lagging behind European peers when it comes to foreign direct investment: only about 1% of its FDI ends up on the African continent. European countries are already a significant investor in Africa, which received EUR75.3bn or 5.2% of Europe’s global FDI in 2021. But Germany remains a smaller player: the UK and France play a major role with a stock of investment equivalent to EUR59bn and EUR54bn respectively, followed by Italy, Switzerland and the Netherlands. In 2021, German companies invested EUR1.6bn in Africa (compared to EUR15.3bn from the UK), with total investments between 2017 and 2021 adding up to EUR6.4bn (Figure 10). Not only is this sum tiny compared to what Germany invests in other regions, but it has also been stagnant for years. In contrast, the stock of investment by French firms has nearly quadrupled and Chinese investment has shown the fastest growth, expanding by a factor of 40 since 2005.

German investment is also very concentrated in a few African countries, mainly South Africa and Egypt, followed by Nigeria, Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria. More than half of Germany's direct investment flows into South Africa, where more than 400 German companies employ about 65,000 people.

With stagnant investment, the significance of German enterprises for African economies is shrinking. Since German FDI is mostly concentrated in manufacturing as opposed to natural resources, companies could miss out on opportunities to partner with Africa in the green energy transition.

In this context, Germany and the EU need to drive already existing policy initiatives meant to increase investment in the region and to create a beneficial partnership. Due to the proximity between Europe and Africa, both could benefit from greater diversification and reduction of dependencies. On the other hand, Africa can put its undervalued potential in critical raw materials, renewable energy resources such as wind, solar, geothermal and hydroelectric power to use. The EU has signed off on several new strategic partnerships and projects to encourage investment and job creation in the region, including the EU-Morocco green partnership, the EU-backed Hydrogen Accelerator and a strategic partnership regarding critical materials and green hydrogen with Namibia. But there is clearly room to grow, particularly regarding cooperation and investments in sectors such as clean and affordable energy, new technologies, finance and a circular economy, including also the processing, refining and value add stages in manufacturing.

Yet, local content requirements and regulatory changes with respect to critical raw materials present a potential threat to foreign investors as African countries are increasingly adopting resource-based and broader industrial development strategies that are centered on domestic value added. Some African countries have restricted raw mineral exports and require firms to set up local processing plants. This trend is likely to continue, which means that investing firms should consider in-country value added when making investment decisions and put in place appropriate strategies to mitigate country risk.

In focus – Policy rate decisions − end of the beginning or the beginning of the end?

Sources: Refinitiv Datastream, Allianz Research

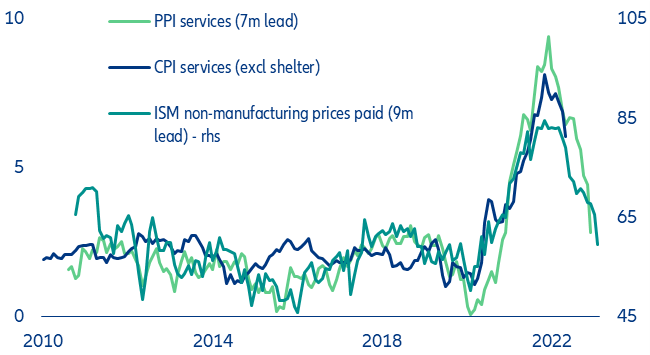

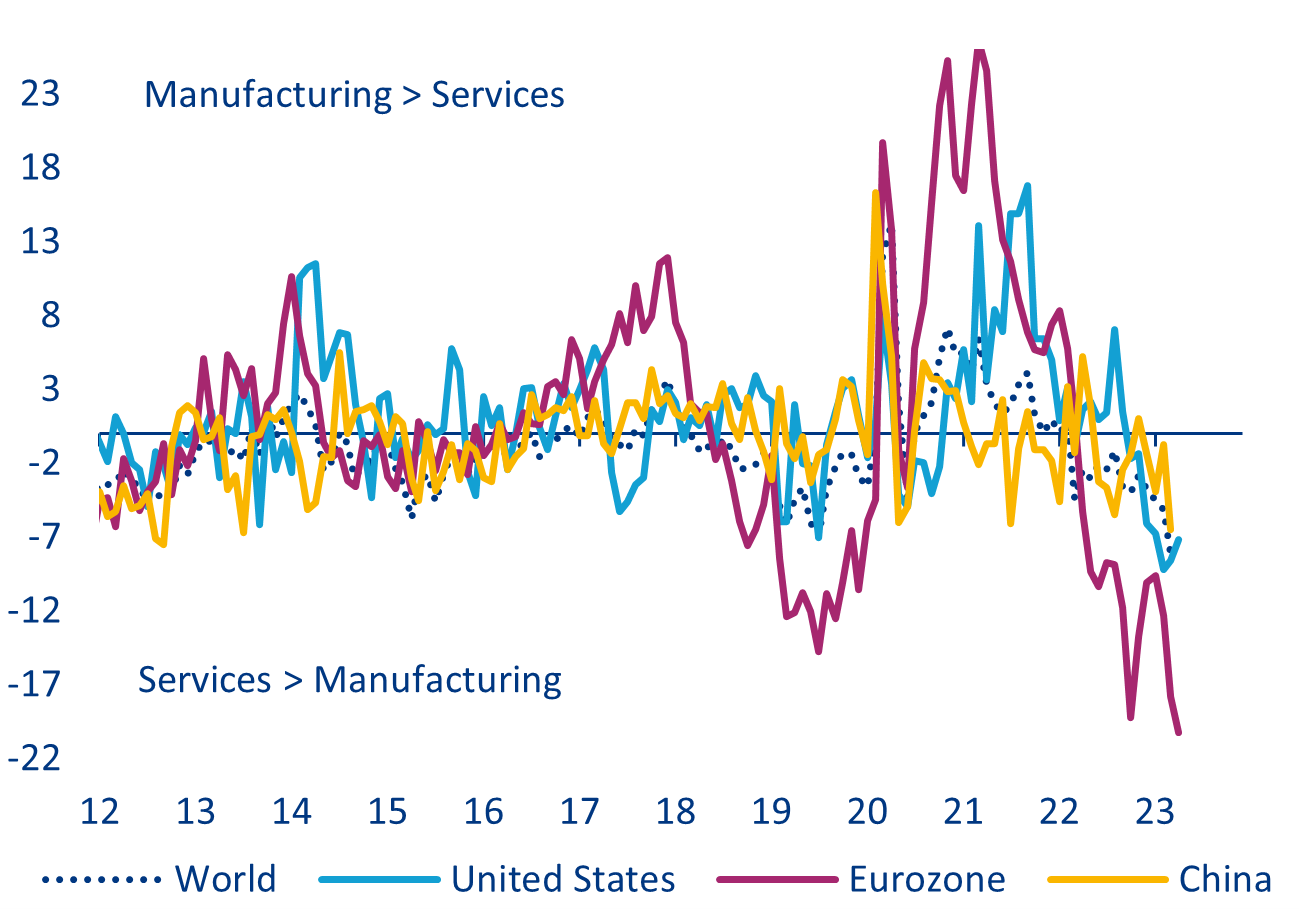

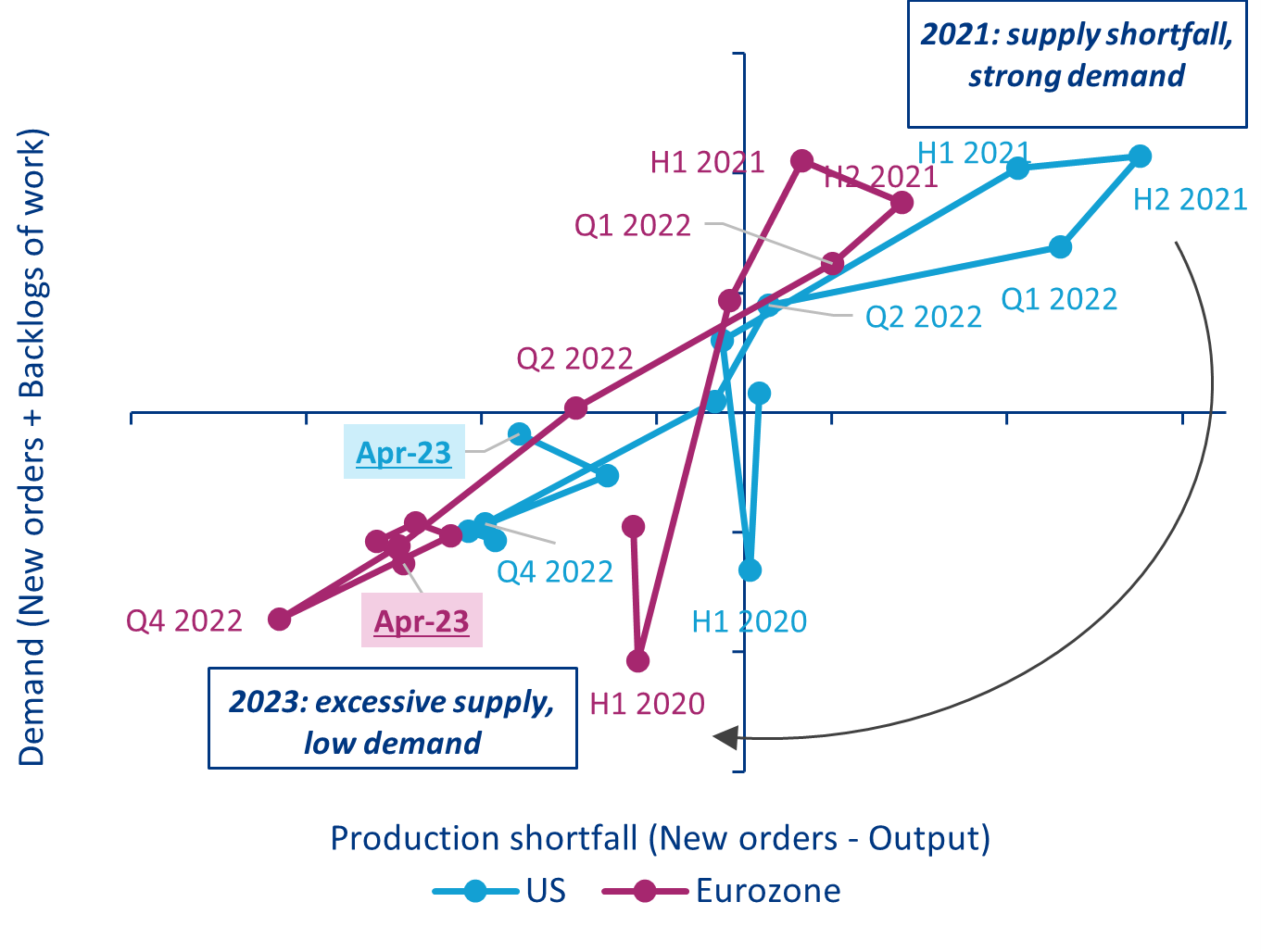

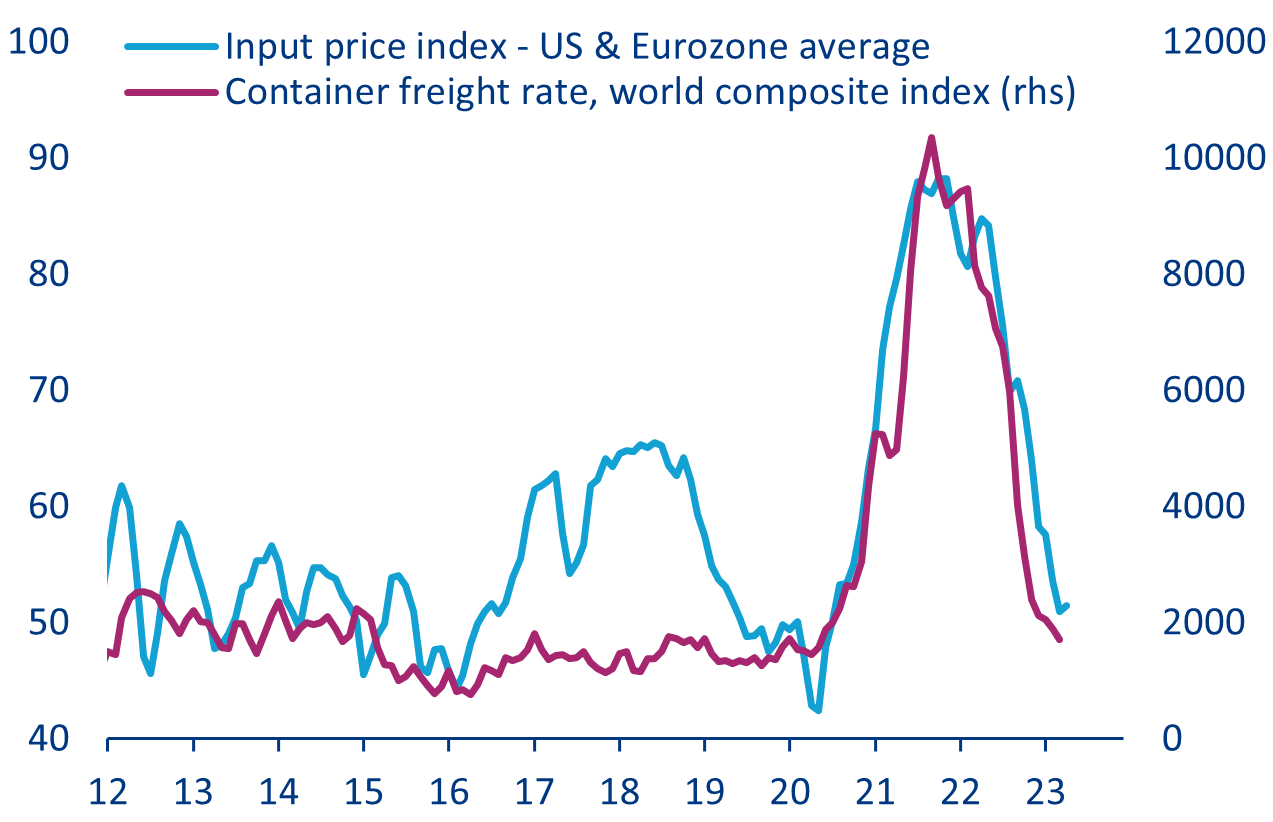

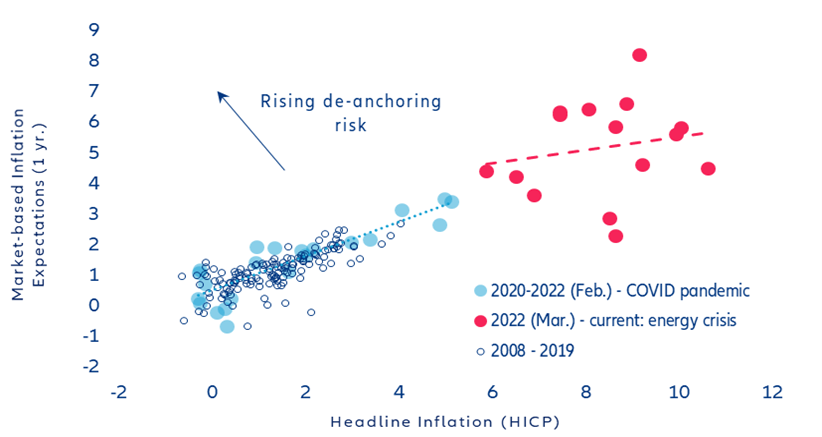

So should the US Federal Reserve and the ECB keep hiking rates or prioritize financial stability over price stability? And above all, considering that the full effects of monetary tightening have yet to materialize, does the current pace of declining inflation warrant further rate hikes at all? For the US Federal Reserve and, to a lesser extent, the ECB, financial stability concerns have already complicated the challenge of setting policy rates to bring down inflation without inflicting excessive damage to growth (and employment). This trade-off is inherently more difficult to manage in Europe, where supply-side pressures, especially due to high energy prices, have had a stronger impact on inflation dynamics in the past. Overall inflation has declined (and more so in the US); however, core inflation is becoming increasingly sticky, especially in the Eurozone, where wage pressures increasingly drive higher prices for services.

In any event, the fight against inflation is likely to become more prolonged unless tightening financing conditions due to more restrictive bank lending slows demand and thus reduces inflation sufficiently to allow the Fed and the ECB to tread more carefully.

Eurozone: more hikes to come

Despite rapidly declining energy inflation, the broadening of price pressures still creates a challenging environment for monetary policy in the Eurozone. In March, headline inflation declined to 6.9% y/y (-1.6pps relative to February), the lowest rate since the start of the war in Ukraine in February 2022. However, core inflation rose to a record 5.7% y/y (+0.1pp). Selling-price expectations show a clear divergence between goods and services. While goods inflation moderated, suggesting that the easing in supply bottlenecks and falling energy prices have started to feed through, price pressures for services remain strong. Nonetheless, the breadth of inflation marginally narrowed, with the share of inflation components registering (y/y) price increases above the ECB’s 2% target declining to 89% (-2pps). In addition, the risk of de-anchoring inflation expectations has declined − consumer expectations have eased while market- and survey-based inflation expectations (ECB’s Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) and Survey of Monetary Analysts (SMA)) have remained stable. We expect headline inflation to average 5.6% this year and 2.6% next year.

Fed: last rate hike in May, then on pause for six months as tighter credit conditions bite economy

In contrast, the Fed is on track to deliver the last rate hike in this cycle (25bps). Although pressures have built in recent days on First Republic bank, the FOMC members will be relieved that the banking crisis has somehow stabilized, with overall regional banks seeing a return of deposit inflows in April. At the same time, while there is increasing evidence that inflationary pressures have started to ease (see below), the Fed will continue to focus on still-elevated current core inflation outturns, which rose +5.6% y/y in the March CPI report (+0.1pp from February). The May FOMC meeting will thus provide Fed policymakers with an opportunity to strengthen further their anti-inflation credentials by pushing the target range of the Fed funds target to 5-5.25%.

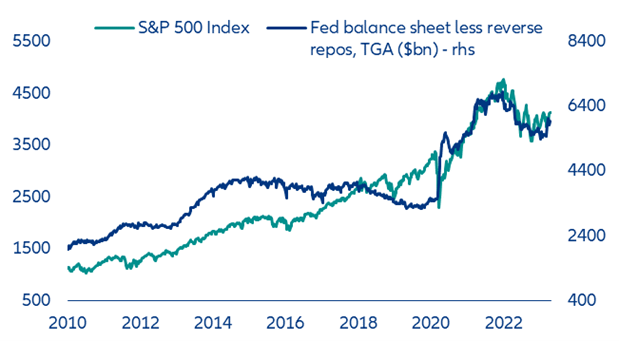

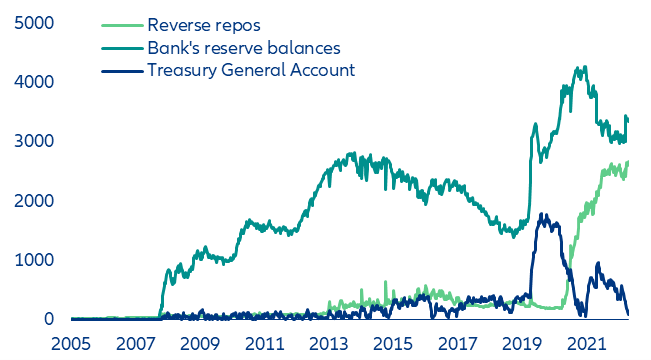

From an anti-inflation credibility perspective, the increase in liquidity – fueled by the banking crisis and the debt-ceiling drama – is unwelcome. It gives the Fed even more arguments to keep rates high for the next few months. Besides, while we think that tighter credit conditions and a weaker economy are already baked into the cake (see below), the Fed may push back against the idea that the rise of its balance sheet since March could fuel inflation down the road. As Figure 16 shows, the Fed’s balance sheet corrected by the Treasury General Account (TGA) and the reverse repos – which is a better measure of underlying liquidity – has picked up substantially since the banking crisis, fueling a rise in the stock market. The rise in Fed’s ‘corrected’ balance sheet has been the result of i) a sharp pick-up in emerging lending to the banking sector in March and ii) the rapid drawdown of the TGA by the federal government, which is seeking alternative sources to fund its deficit as it approaches the debt ceiling limit (fixed at USD31.4trn).

Tighter lending conditions and recession... As we argued recently, the maximum impact of monetary tightening will likely be reached between the middle of 2023 and early 2024, supporting our call of a recession in the second half of 2023. This is because rapidly tightening bank credit standards since the middle of 2022 should eventually lead to a pull-back in new loans to the private sector in the second half of the year, according to usual lags. We also think that property price declines are not over yet, with adverse effects on consumption spending, which will start to show by early 2024. Our estimates show that tightening credit conditions and falling house prices should be enough to push the US economy into a recession.

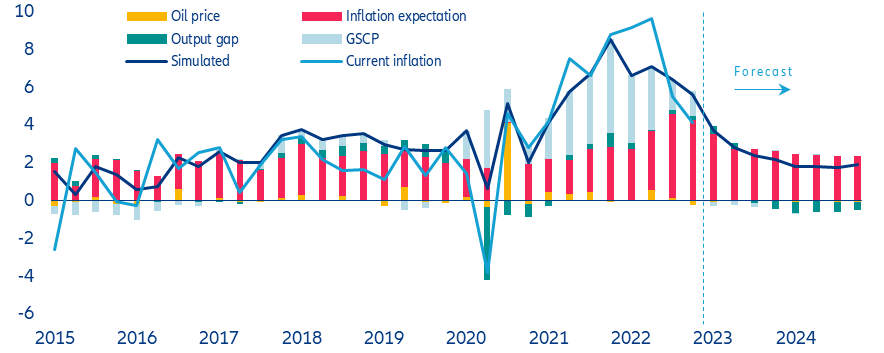

… the only way out of inflation? As such, we expect a -1% decline in GDP between June and December 2023. Such a squeeze in demand should be sufficient to pull inflation down to close to the Fed’s 2% target by Q2 2024, according to our Philips curve equation that links inflation to the output gap and other determinants. We expect the output gap to turn negative by Q3 2023, which will pull down the pace of quarterly price increases to +2% – compatible with inflation normalizing toward 2% on a y/y basis (Figure 18). Note that the effect of the output gap on inflation is more than suggested by its headline contribution. A negative output gap pulls down current inflation, which in turn weighs on inflation expectations, further contributing to the fall of current inflation. The fact that inflation has become more sensitive to the output gap since the pandemic (i.e. the Phillips curve has steepened) also strengthens the argument that a recession should allow inflation to normalize.

Sources: Refinitiv Datastream, Allianz Research. Note: GSCP = Global Supply Chain Pressures index.