- The US economy has been remarkably resilient to the sharpest monetary tightening in decades. While the housing market started feeling the pinch as early as summer 2022, GDP in the first quarter of 2023 is expected to show robust underlying domestic demand, buoyed by robust consumer spending.

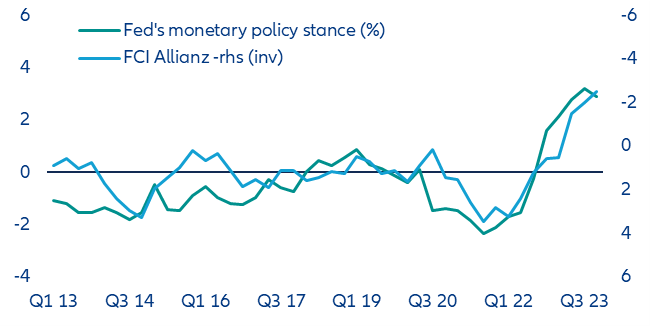

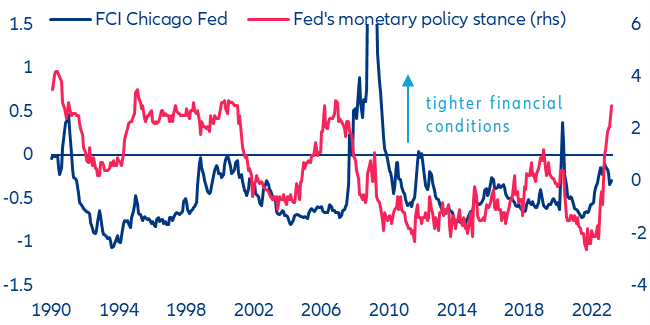

- The Fed’s very restrictive policy stance has also not fed through to tighter market-based financial conditions. Even the recent banking turmoil has not led to tighter financing conditions overall as Treasury yields have dropped and the stock market has remained resilient (excluding bank shares).

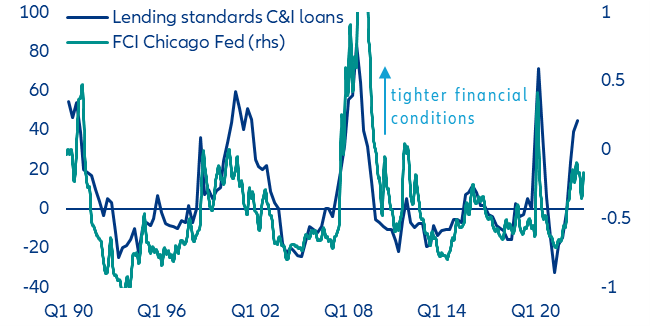

- But lending standards have tightened rapidly since last year, and the real property-price decline is bound to accelerate. Banks’ lending standards on new loans and real property prices already point to a significant drag on GDP in the second half of 2023 through negative wealth effects and a pullback in bank loans. The downturn in property prices is far from over, according to signals sent by monetary aggregates.

- The Fed’s restrictive monetary policy will probably reach its peak impact around end 2023/early 2024. It will knock GDP by at least -2pps. The exact timing is subject to large uncertainties. Risks lie on the downside if market-based measures of financial conditions adjust to a level more compatible with the Fed’s underlying stance. More banking stress could be the catalyst.

In Focus

US: Credit crunch in the making?

Türkiye – Economic activity shows resilience but external risks remain high

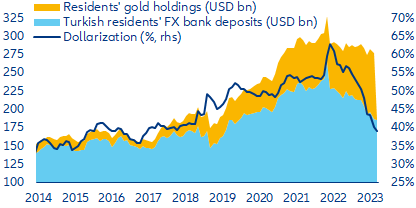

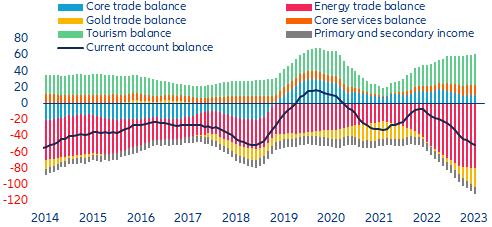

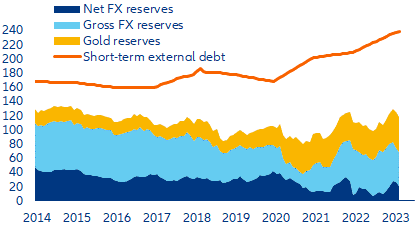

We expect economic growth in Türkiye to remain robust in 2023, with the two earthquakes having only a short-lived negative economic impact. Despite the sharp currency depreciation and surging inflation in 2022, the Turkish economy avoided a recession and grew by +5.6% last year. The damage to critical infrastructure from the tragic earthquakes in southeast Türkiye appears limited and economic output is unlikely to suffer dramatically as the affected region is not home to key industries, accounts for just 10% of GDP and not all output will be affected (for example agriculture). As a result, the impact on GDP will not be as pronounced as that of the 1999 earthquake in northwest Türkiye, which struck the industrial heartland. It is also worth mentioning that, due to a peculiarity of national accounting, GDP can actually be higher after a natural disaster because the rebuilding work is counted as an increase in output, while the initial destruction of property is not recorded as a loss. Compared to pre-disaster forecasts, we expect somewhat lower overall economic activity in the first half of the year but stronger expansion in the second half. Early indicators signal an economic rebound in Q1 2023 from a weak Q4 2022, despite the catastrophe. The manufacturing PMI rose from an average 46.7 points in Q4 to 50.6 in Q1 and the consumer confidence index increased from 76.1 in Q4 to 80.6 in Q1. Overall, we have revised our real GDP growth forecast for 2023 up to +3.1% (from +1.9% as of end-2022).

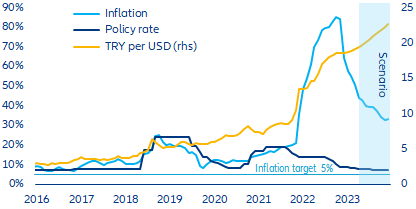

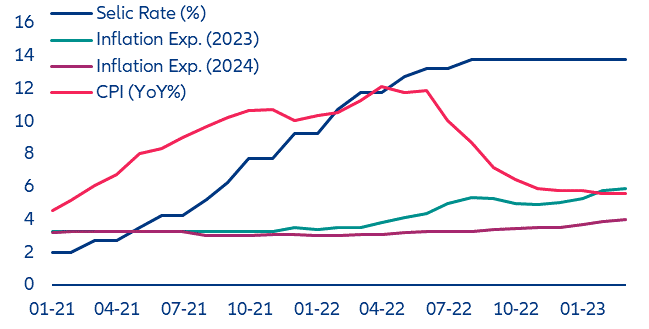

Inflation will decline but nevertheless remain high in 2023 amid ongoing currency depreciation and continued loose monetary policies. Headline consumer price inflation has fallen from a 24-year high of 85.5% y/y in October 2022 to 50.5% in March 2023, mainly due to base effects as the impacts of the severe depreciation of the Turkish lira at end-2021 and the sharp rise in energy import prices on consumer prices have begun to fade. However, we expect the lira to remain volatile and vulnerable, and to depreciate further in 2023, with the forthcoming general elections in May 2023 and potential policy uncertainty around that event being potential trigger points for renewed currency weakening. Moreover, energy prices are set to remain elevated compared to 2019-2021, even if they have slightly moderated recently. Overall, we expect headline inflation to remain above 30% y/y until the end of 2023, and to average more than 40% this year (Figure 1). Nonetheless, the Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye (CBRT) is likely to continue its unorthodox monetary policy stance and will possibly lower its benchmark policy interest rate further by a cumulative 100bps or so by year-end, from 8.5% currently.

Eurozone credit – squeezing rather than crunching

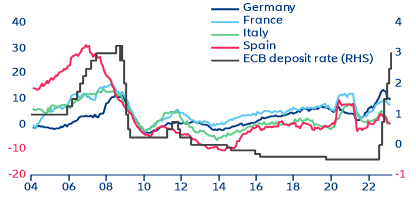

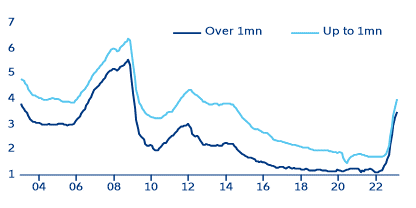

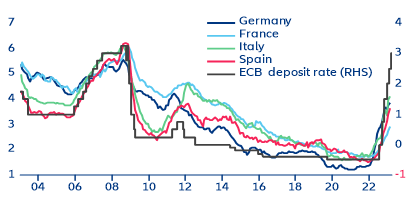

On top of the sharp rise in interest rates, the current turmoil in the banking sector has raised additional concerns over the upcoming dynamics in credit growth across the Eurozone. Since July 2022, the ECB has raised rates by 300bps, which has helped to normalize inflation to 6.9% in March from a peak of 10.6% in October 2022. But as a result of higher lending rates, credit growth to the private sector began to slow down in October (annual rate decreased to 6.6% from 7.1% a month earlier) and then continued down-trending rather slowly (4.3% y/y in February 2023).

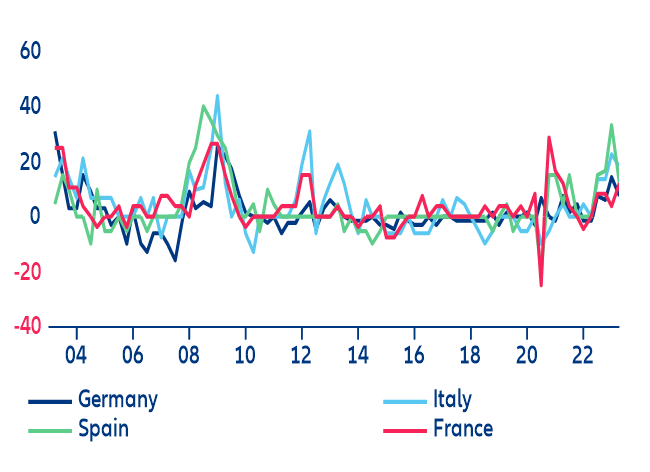

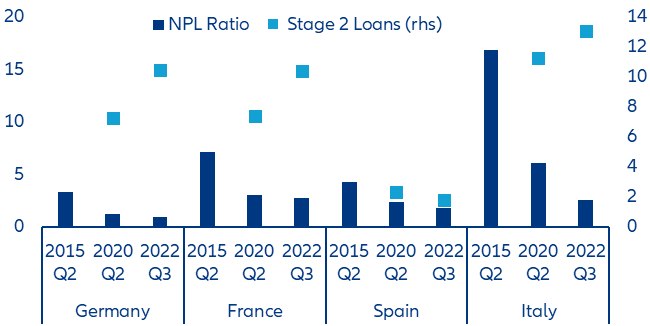

We do not expect credit flows to come to sudden stop in the coming quarters. However, the declining trend will continue as demand is cooling, given higher borrowing costs, and banks continue to tighten credit standards. The UBS-Credit Suisse accident brought European lenders under the spotlight after more than a decade of efforts and improvements following the sovereign debt crisis. Learning from that episode, we believe banks will now privilege the health of their balance sheets and carefully scrutinize loan applications instead of increasing credit volumes. Similarly to the tightening of lending conditions on firm credit seen during the Great Financial Crisis in 2008/2009, credit standards had already tightened for firms in the big four Eurozone economies by the end of 2022. We believe that they will likely tighten further as banks face the pressure of rising interest rates (Figure 7).

Sources: ECB SWD, Allianz Research

Sources: ECB SWD, Allianz Research

Minsky clock – The next shoe to drop

Tightening monetary policy is revealing the cracks in the global financial system. At the heart of the Fisher-Minsky-Kindleberger model of financial bubbles and crises is the idea that stability begets instability. Indeed, from the Great Financial Crisis until 2021, capital markets experienced a long period of low inflation and low policy rates which, alongside pervasive moral hazard, fostered an unfettered hunt for yield. Total indebtedness surged as investors funded risky assets by borrowing funds from banks and non-banks. Since 2021, the shift to tighter monetary policy has revealed the many forms that leverage takes, from reverse factoring (Greensill Capital) and total return equity swaps (Archegos) to interest rate swaps (UK pension funds), more or less properly reported borrowings (Adani) and excessive issuance of tokens (FTX). In the case of Silicon Valley Bank, closer to the center of the financial system, it is the combination of transformation risk (funding long-dated assets with sight deposits), interest risk (a large portfolio of long bonds) and treasury risk (excessive concentration of deposits by SVB’s depositors in one single bank) that proved lethal. These mistakes are so egregious that it is difficult not to think that moral hazard played a role in their inception. Finally, the demise of Crédit Suisse shows how exposure to peripheral accidents (Greensill, Archegos) can contribute to bringing down systemic institutions.

Where will the next financial accident come from? The generally accepted answer is from non-bank financial institutions. To varying degrees, NBFIs are indeed exposed to a bi-dimensional risk known to be lethal: transformation risk (or assets-liabilities mismatch) compounded by market risk on their assets. And NFBIs have grown a lot since 2007-2008 to more than USD60trn on a global scale in 2020.

In the US, at the end of 2021, NBFIs assets were 2.3 times as large as banks’ assets, led by equity open-end funds (26.5% of total), (defined benefits) pension funds (14.6%), ETFs (12.9%), bond open-end funds (10.1%), money market funds (9.5%) and life insurers (9.1%). Pension funds were mostly exposed to equity and corporate bonds, ETFs to equity and life insurers to corporate bonds. Unfortunately, this type of detailed cross-holding matrix (who owns what?) is incomplete: it does not say anything about the exposure to commercial real estate or more generally alternative assets. Yet, the withdrawal requests faced by Blackstone’s Real Estate Income Trust show that non-listed assets are not immune to a liquidity crisis. As this kind of detailed cross-holding matrix is not available in other jurisdictions, there isn’t enough information to fully assess the risk of contagion in the global financial system.

Brazil – New fiscal framework, an end to uncertainty?

New government, old challenge. With the debt-to-GDP ratio likely to approach 100% of GDP by 2026, fiscal consolidation is top of the agenda for Brazil’s new government. Last week, the Ministry of Finance announced a new fiscal framework to replace the spending cap in place since 2017. The proposal limits the variation in expenditure to 70% of the variation in revenue observed over the previous 12 months (up to July). It also sets a floor and ceiling for real expenditure growth, which cannot be less than 0.6% or more than 2.5% per year. In addition, the framework provides for a primary surplus target (plus or minus 0.25%) and a mechanism to block expenditures in case of non-compliance. Thus, if the surplus crosses the upper limit of the band, it is used for investment in the following year. If it is below the floor, spending increases less in the following year: 50% of the increase in revenue. With the new rules, the government estimates that it can achieve a surplus by 2025[3].

The framework has several positives, but the devil is in the details. The limit on overheads, trigger for course correction and commitment to even save some revenue are all steps in the right direction. However, one of the main problems is the link between expenditure and revenue because it is very difficult to cut expenditure, much of which is fixed. Even discretionary spending is very difficult to cut, especially in times when tax revenues are growing less or even falling. The government has not yet laid out how exactly spending cuts will be made. For the new fiscal framework to be credible at a time of no GDP growth, it needs to be accompanied by expenditure reform.

As a result, the government will need to significantly increase its revenues. In recent years, Brazil’s government benefited from substantial revenues amid higher inflation, the commodity prices boom and the reopening of the economy after Covid-19 lockdowns. With these conditions unlikely to be repeated, the government will have to find new sources of revenue to meet the ambitious primary outcome targets that are important for stabilizing the public debt-to-GDP ratio.

According to Minister of Finance, revenue needs to increase by between R$100 billion and R$150 billion to make the plan credible and balance the public accounts. To achieve this goal, the government's strategy would be to tax those who don't pay taxes. Indeed, new measures are expected to be announced soon that will, among other things, increase taxation in new segments (e.g. electronic sports betting), tax investment funds and even try to reduce tax exemptions, although the latter is likely to be politically difficult to implement. For now, a tax increase is not being considered but cannot be completely ruled out in the medium term as the government will still have to contend with Congress and political lobbies over the other tax changes. It will also most likely try address the income tax framework in a second phase of the ongoing tax reform.

Overall, the framework could lead to very slow debt convergence. Success depends on a significant increase in revenues and/or an increase in real GDP growth, which we do not expect to exceed +2.5 % by 2026. Therefore, we think the government has been rather optimistic in setting the parameters for interest rates and real GDP growth, which suggests a likely adjustment in the primary surplus targets.

While markets reacted positively to the announcement – the BRL appreciated by 1.2% – it is too early to declare victory. As further clarifications are needed, we expect volatility in the short term. Meanwhile, despite government pressure on the central bank, we do not expect an immediate interest rate cut until a sound and credible fiscal framework is released and inflation expectations come down.

Sources: ECB SWD, Allianz Research

US – Credit crunch in the making?

The Fed’s sharpest monetary tightening in decades has so far knocked the US housing market, but the overall economy has remained remarkably resilient. In 2022, the Fed embarked on its fastest monetary tightening since the 1980s. Interest rates were first raised in this cycle in March 2022, but the pace of rate hikes accelerated from June 2022. The Fed delivered four successive 75bps rate increases until November 2022. The balance sheet started to decline in July 2022 through the run-off of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and Treasuries. As the most interest-rate sensitive sector of the economy, the housing market was the first to feel the pinch, with transactions and construction activity slumping since summer 2022. However, the overall US economy has shown few cracks so far. GDP expanded by a healthy above-trend +3.2% in Q3 2022 and +2.6% in Q4 2022 (annualized). But the underlying picture of the economy is less rosy. Domestic final sales growth – a better gauge of the health of the domestic economy, which excludes the effect of net trade and inventory swings – stalled at a lackluster +0.7% in Q4 2022. However, we expect GDP to have grown a robust +2% in Q1 2023 (data to be released on 27 April), and that underlying domestic demand has actually picked up pace, boosted by consumer spending. So the question is, when will the Fed eventually pull down the economy?

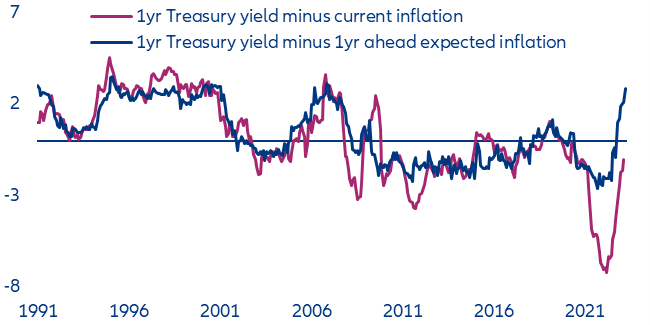

Market-based measures of financial conditions appear too loose with respect to the Fed’s restrictive stance. The Fed’s monetary stance is best measured by the real interest rate because what ultimately matters for companies and households that need to borrow money is the real rate of interest, not the nominal one. However, we think a basic mistake some financial analysts make is to take current inflation to calculate the real interest rate. Since interest is a forward-looking variable (i.e. how much will be owed at some future date), the relevant comparison with inflation is also forward-looking (i.e. how much will prices change by that same future date). Our preferred measure of the Fed’s stance is thus defined by the 1yr Treasury bill yield, deflated by 1yr inflation expectations, derived from the Cleveland Fed (a measure which draws on both bond pricing and survey data). Under this metric, real rates have soared to above 2%, the highest since 2007 (Figure 11).

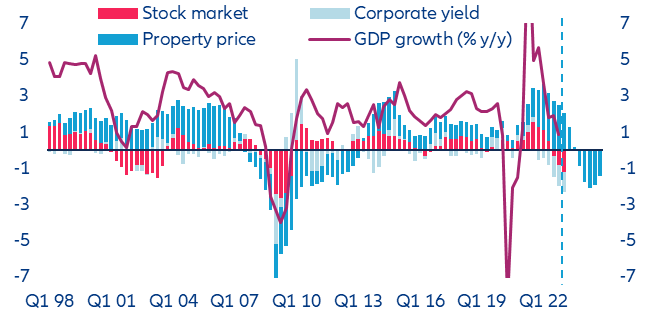

But tighter lending standards and falling house prices are already baked into the cake. We estimate they will have the maximum impact on GDP by early 2024 – almost two years after the Fed started hiking rates – to the tune of -2pps. We do not know for certain whether, or by how much, market-based financial conditions will tighten in coming weeks or months. Nevertheless, even if market-based financial conditions do not tighten much further, we think that falling real house prices and tighter lending standards will take an increasing toll on the economy from the second half of 2023.

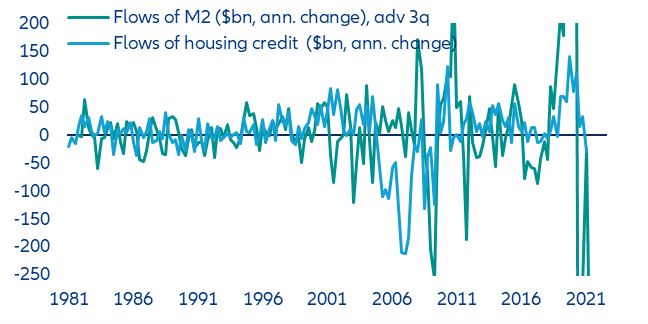

Our previous research has shown that tighter lending standards signal a sharp pull-back in commercial & industrial loans and credit card loans from the second half of 2023 to Q1 2024. We now look at the GDP impact of house prices using our proprietary statistical model linking GDP, real equity prices, real 10-yr corporate yields and real house prices (using the S&P Case-Shiller index). As we have highlighted before, the rapid contraction in M2 flows signals a sharp pullback in housing credit flows in the next three quarters (Figure 14). This in turn suggests house process could decline by -10-15%. Real house prices started to decline in June 2022 and are now -5.7% off their peak.