- Recent efforts by some emerging market (EM) countries to diversify their currency reserves away from the US dollar have raised questions about the beginning of the end of USD dominance. However, the dynamics affecting the US dollar’s role as reserve currency are far more intricate than official statistics suggest and any material decline in the role of the US dollar in global finance will take much longer than current headline news on de-dollarization insinuate.

- The private sector’s use of the US dollar for trade and investment rather than the portfolio allocation choice of central banks will shape the currency’s status. The role of the USD in private sector transactions has remained virtually unchanged, with only slight adjustments based on FX turnover, bond issuance by non-financial corporates and SWIFT payments. In addition, reserves are predominantly invested in safe and liquid assets, but the non-US dollar investment universe remains too small and fragmented to absorb reserves demand, especially in those EM countries that have been most critical of their US dollar dependence.

- Over the long term, the incipient fragmentation of global trade and more diversified oil demand – if persistent – are bound to strengthen the case for USD alternatives. The Gulf countries, which play a crucial role in supporting the USD (e.g. via oil prices and large USD reserves to maintain the peg), are increasingly looking towards China due to the structural changes in the oil market. Similarly, slowing globalization, driven by events like the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, has prompted – among other things – some countries to use non-USD currencies for bilateral trade, which will chip away at the share of USD in total reserves globally – but any significant change will take a long time.

What to watch:

- Airlines – I feel the need, the need for speed – The thirst for travel despite rising airfares as well as declining jet-fuel prices are speeding up the recovery for airlines

- US housing market update – US housing construction activity is in a modest recovery mode and prices are picking up again

- PMI downward momentum – Recent sentiment indicators reveal that economic activity in France and Germany has cooled noticeably

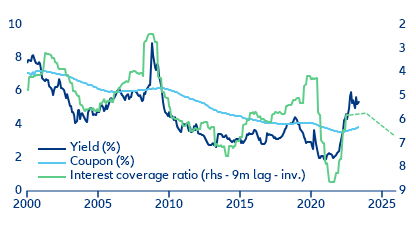

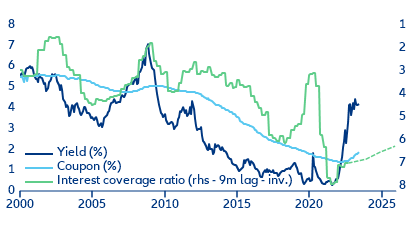

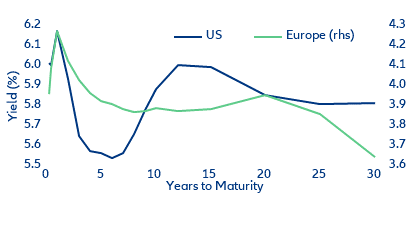

- Corporate debt maturity profiles in Europe and the US – Higher interest rates will increase corporate borrowing costs further until the end of next year

In focus – De-dollarization of FX reserves? Not so fast…

Airlines – I feel the need, the need for speed

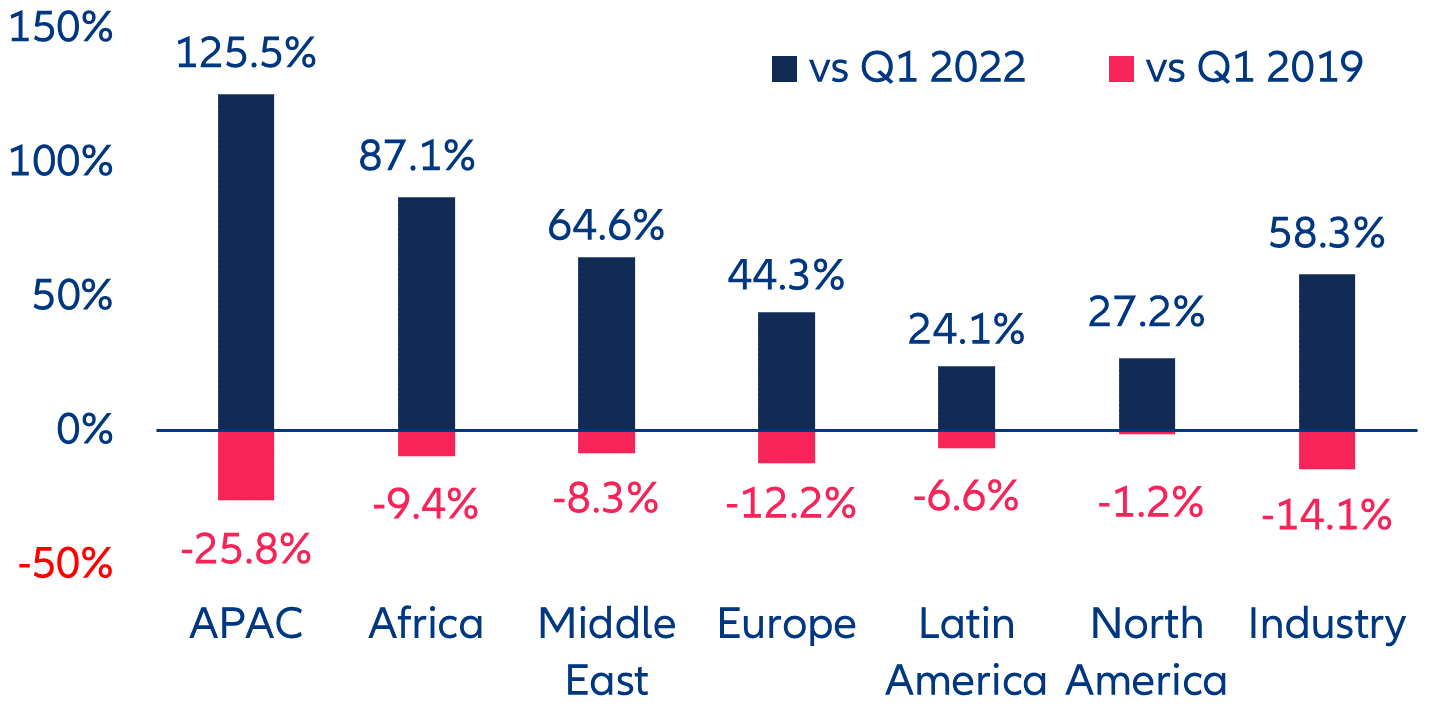

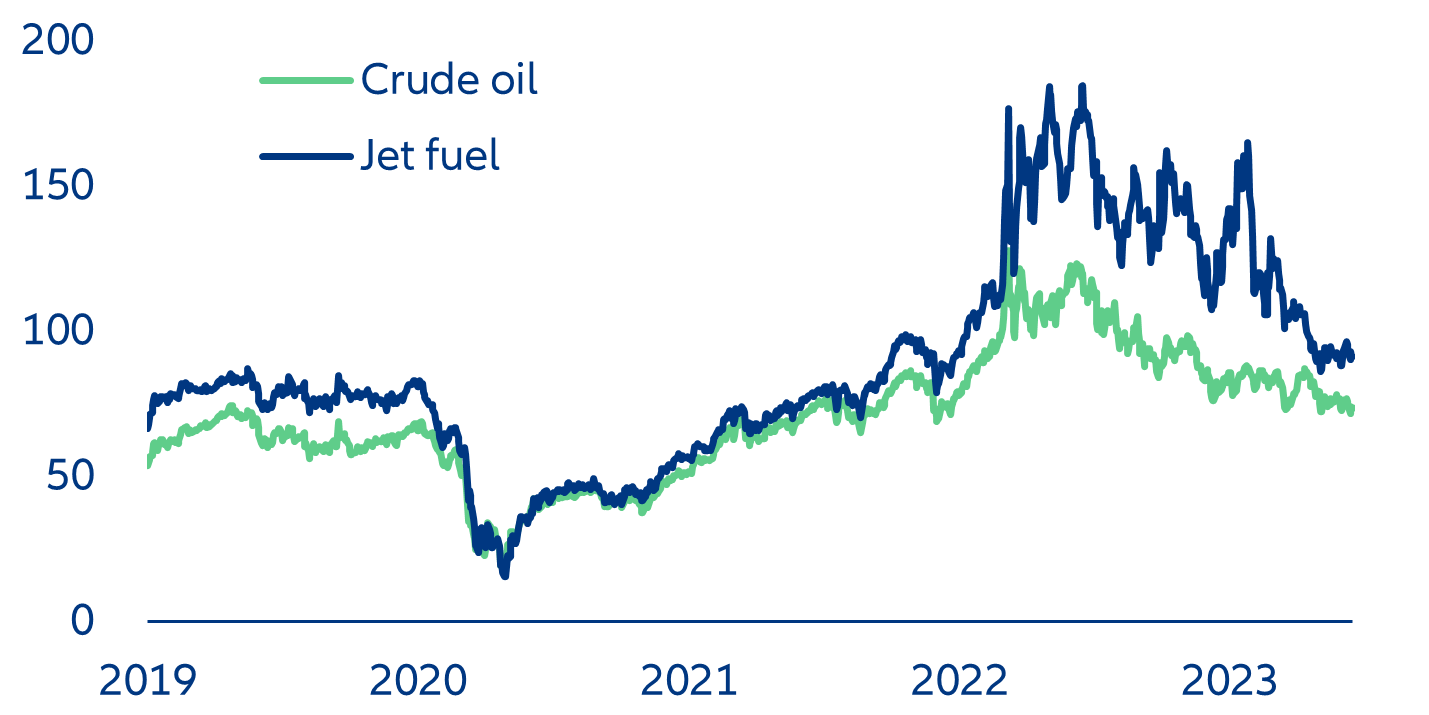

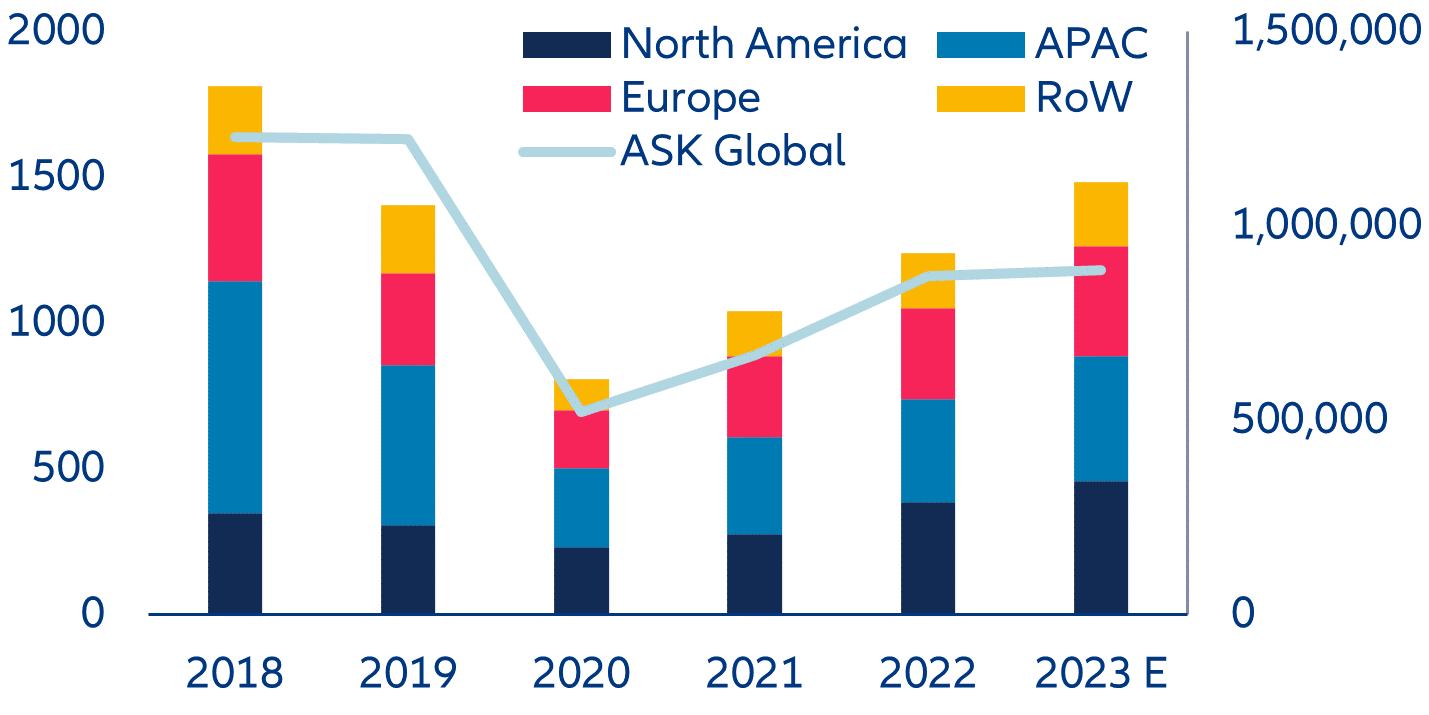

Airlines’ margins are benefiting from rising airfares and declining operating expenses. Even though jet-fuel prices, which represent 30% of sales, remain above the pre-pandemic level, they declined by -36% to USD91.3/bbl this year, about half of the crisis peak of USD184.8/bbl in June 2022. At the same time, airfares have increased, especially for international routes such as those between the US and Europe (+23% YTD on average, Figure 2).

After three loss-making years, the airline industry may break even in 2023 – earlier than expected. According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), total revenue is expected to rise +9.7% y/y to USD803bn (vs USD838bn in 2019), and net profits could to jump up to USD9.8bn this year (vs USD26.4bn in 2019), with North American carriers recording the strongest results.

US housing market – bottomed-out?

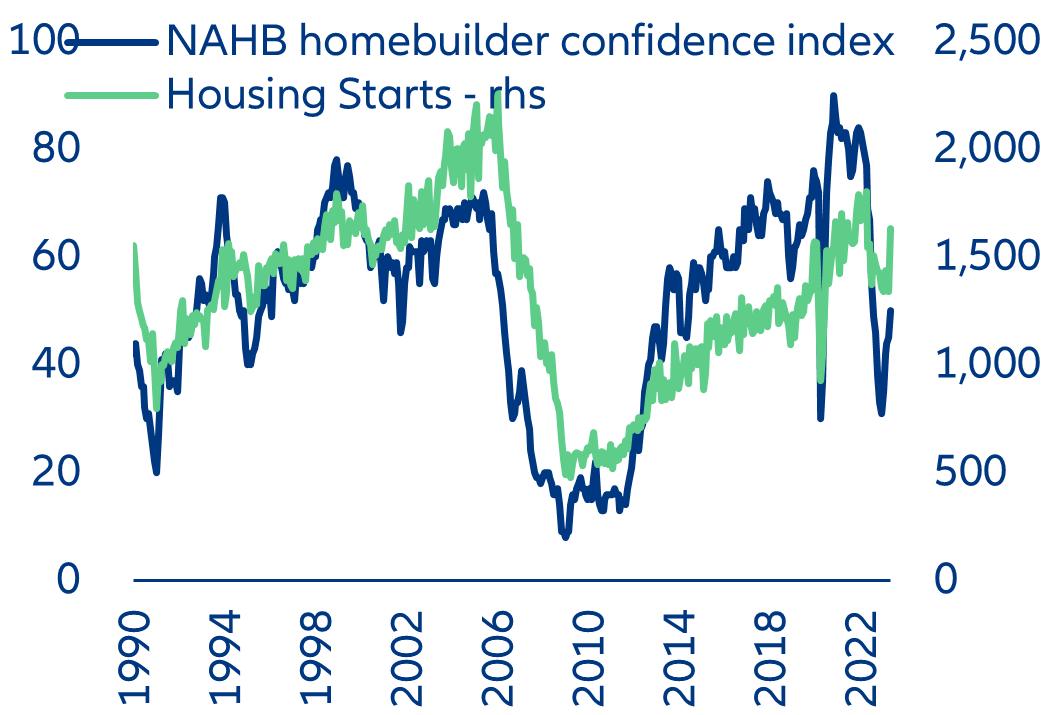

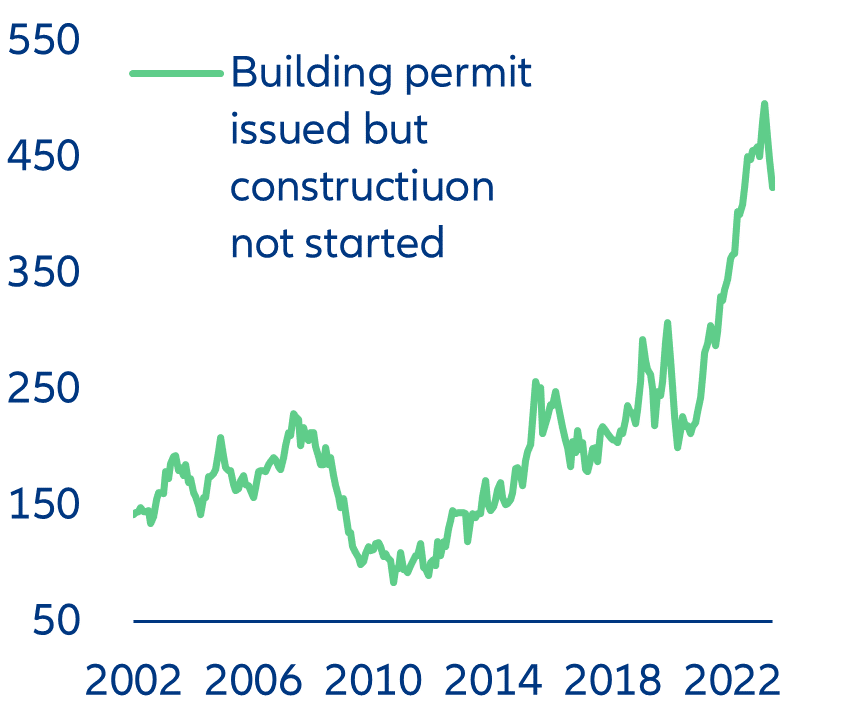

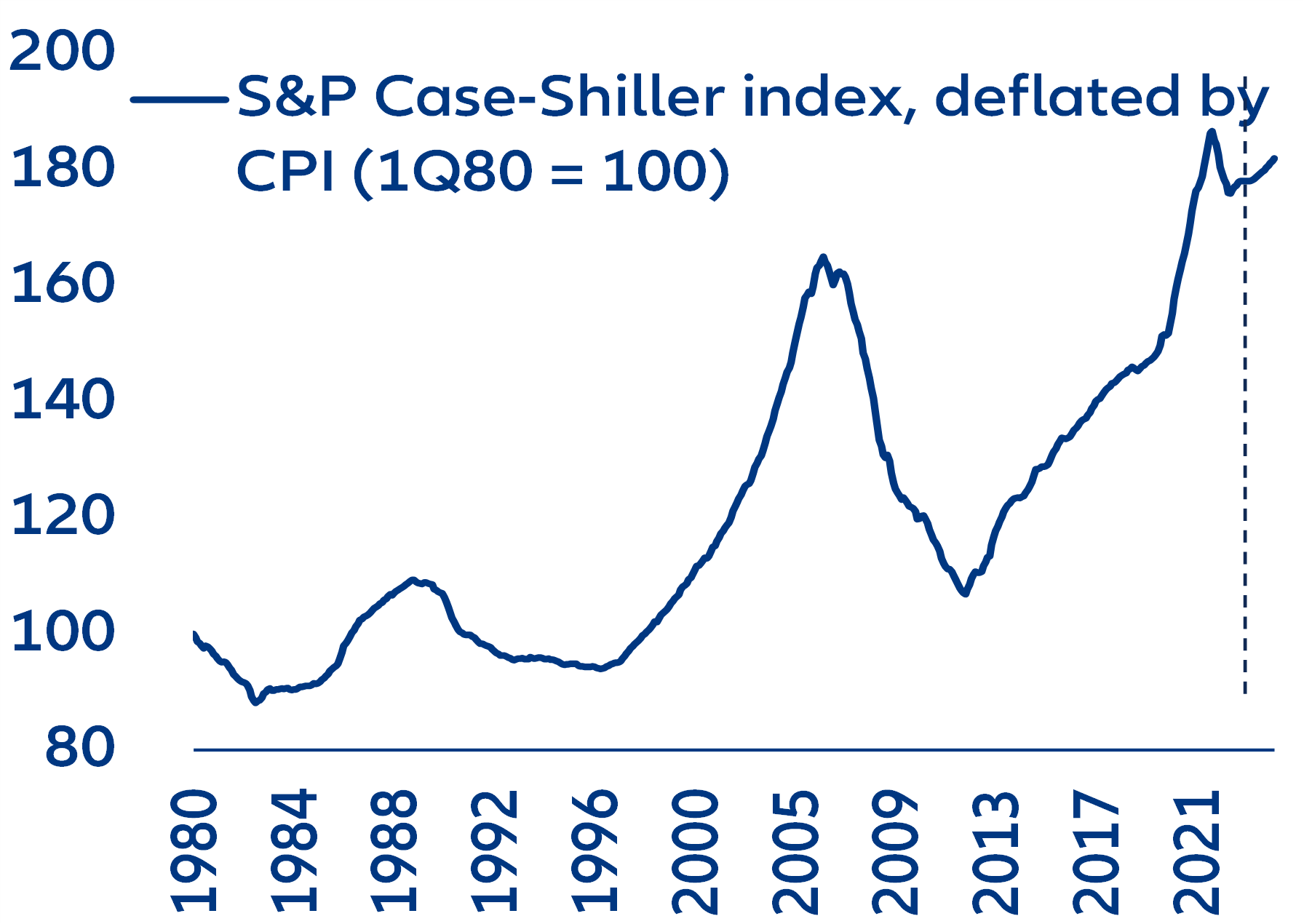

The US housing market has been in a downturn over the last two years but it seems to have reached its end. The Federal Reserve’s hiking cycle pushed benchmark mortgage rates above 6% since end-2022. Elevated borrowing costs together with still-high property prices have deterred US households from purchasing existing homes or building new ones. According to the national accounts, private residential investment slumped more than -20% between Q1 2021 and Q1 2023. However, private housing starts jumped in May as homebuilder confidence is rapidly improving (Figure 4, left). Furthermore, the prior decline in housing activity is likely overstated by the national accounts because of measurement difficulties. More generally, several structural and pandemic-related factors are keeping the US housing market tight in this cycle: (1) strong aggregate household balance sheets, with large liquid assets and a high net-worth-to-income ratio; (2) the recovery in immigration; (3) relatively low housing supply as indicated by low homeowner vacancy rate and (4) the resorption of supply shortages, which is leading to a pick-up in completions as large backlogs are being cleared (Figure 4, right).[2]

We expect residential investment to increase by +1% from Q1 2023 to Q4 2023, and +4.3% in 2024. The very large amount of construction backlogs to be cleared presents some upside risks to our forecasts. However, prolonged tight monetary policy until at least next year should keep the housing recovery sluggish amid persistently high mortgage rates and tight credit conditions.

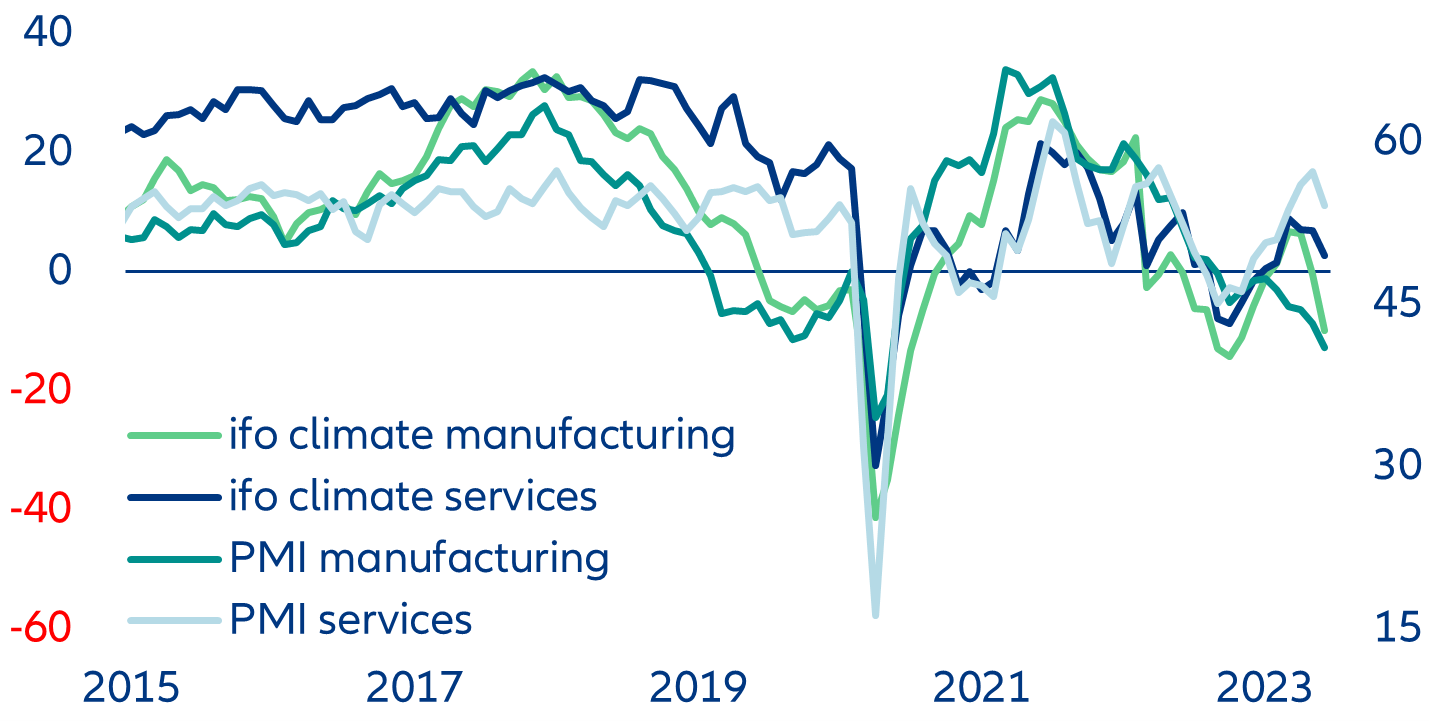

Negative PMI momentum

The outlook for economic activity in the largest Eurozone economies remains a mixed bag...for now. In Germany, another quarter of negative growth in Q2 seems likely and growth will underperform relative to France, where sentiment still holds up better. But the weak June PMI for France suggests that our expectations of a GDP drop in France in Q3 are materializing. After a positive surprise in Q1, Italy’s positive momentum might not hold; consumers are increasingly upbeat but businesses remain less optimistic. In Spain, available data so far seem to be consistent with still resilient economic activity in Q2. This momentum should continue into the summer, supported by the services sector and the strong rebound in tourism. But the question remains how Spain will sustain its current growth rate as other large Eurozone economies are slowing.

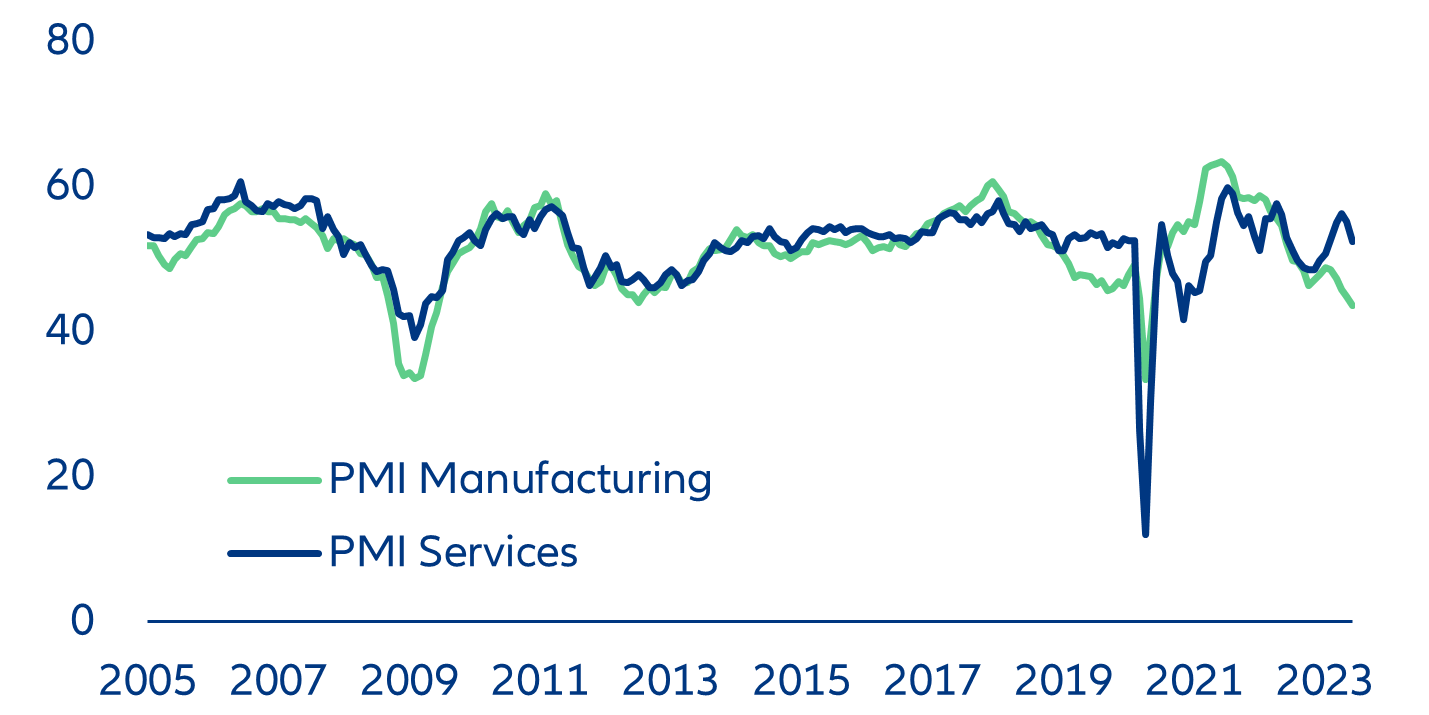

These poor results suggest continued stagnation in the Eurozone. The Eurozone composite business activity index fell to its lowest level since the beginning of the year. The manufacturing PMI came in at 43.6 and the services PMI plunged by 2.7pps compared to May 2023 (Figure 7). Manufacturing has been at its lowest level, apart from the pandemic dip, since the economic and financial crisis in 2008/2009 when the Eurozone economy shrank by more than -5%. While services have so far held up better than manufacturing, the sharp plunge brings both closer together again, with the consequence of a gloomy economic outlook for the Eurozone as a whole for the rest of the year.

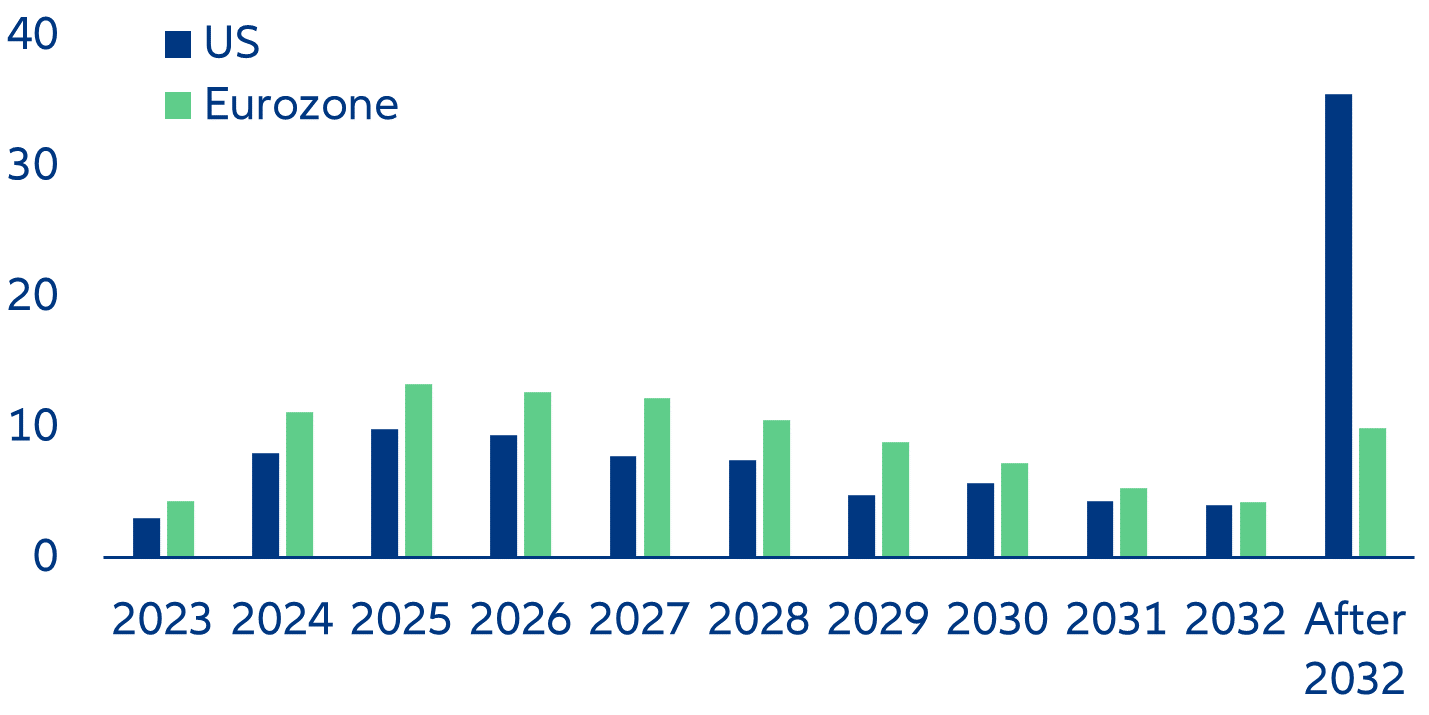

Corporate debt maturity walls in Europe and the US

In focus – De-dollarization and FX reserves? Not so fast…

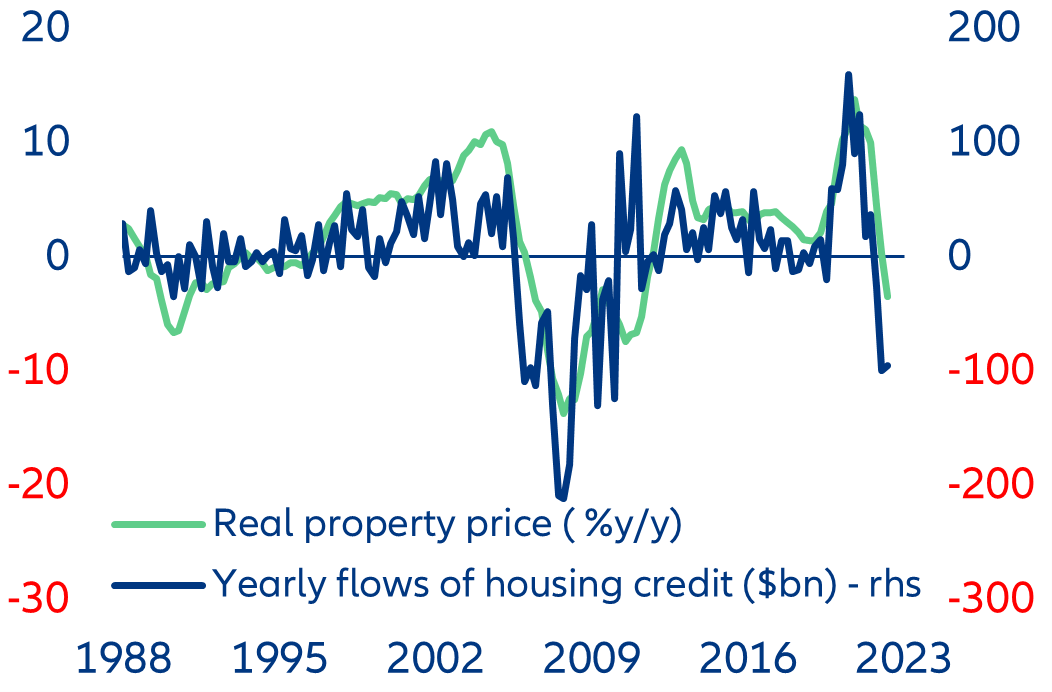

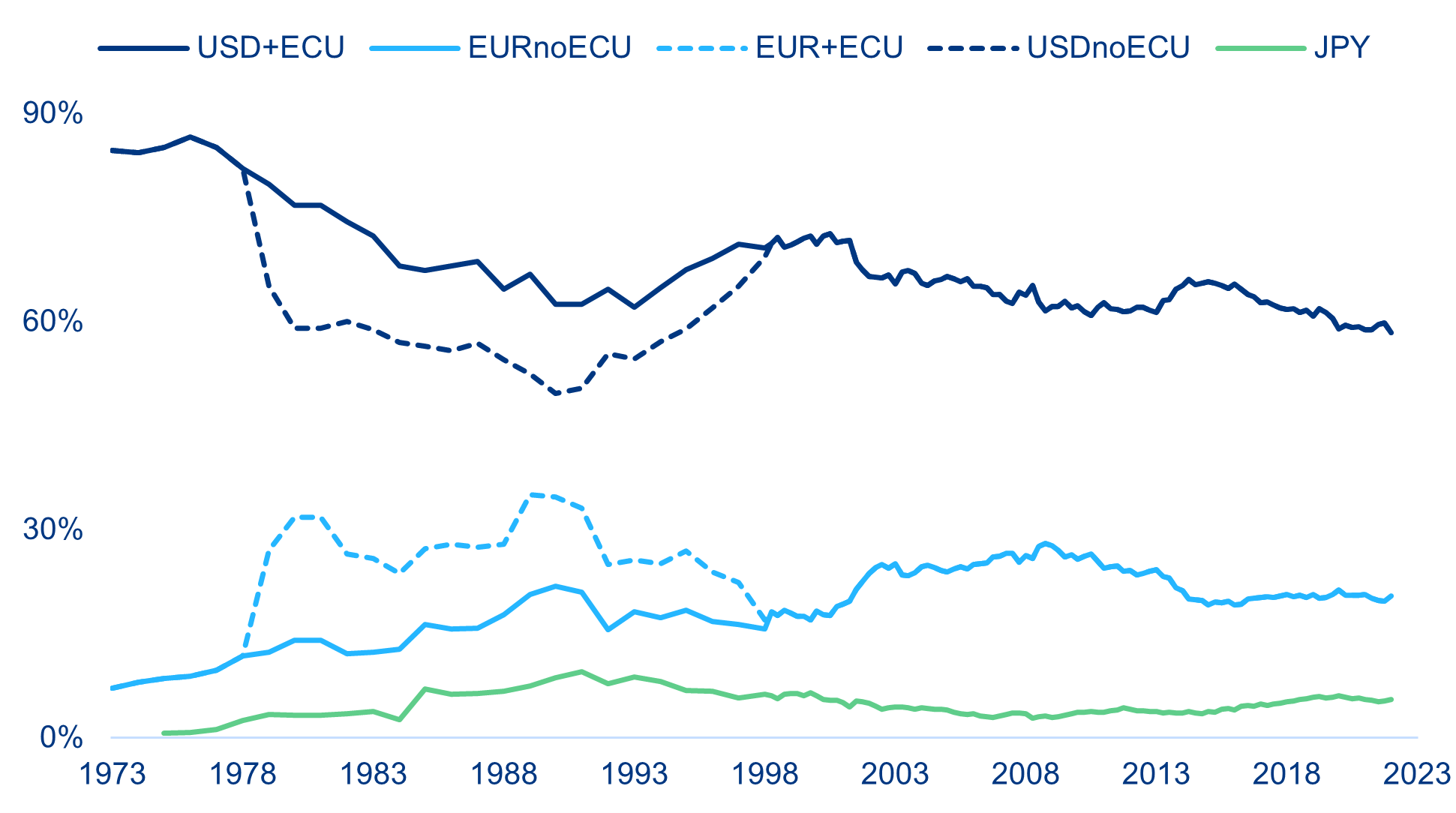

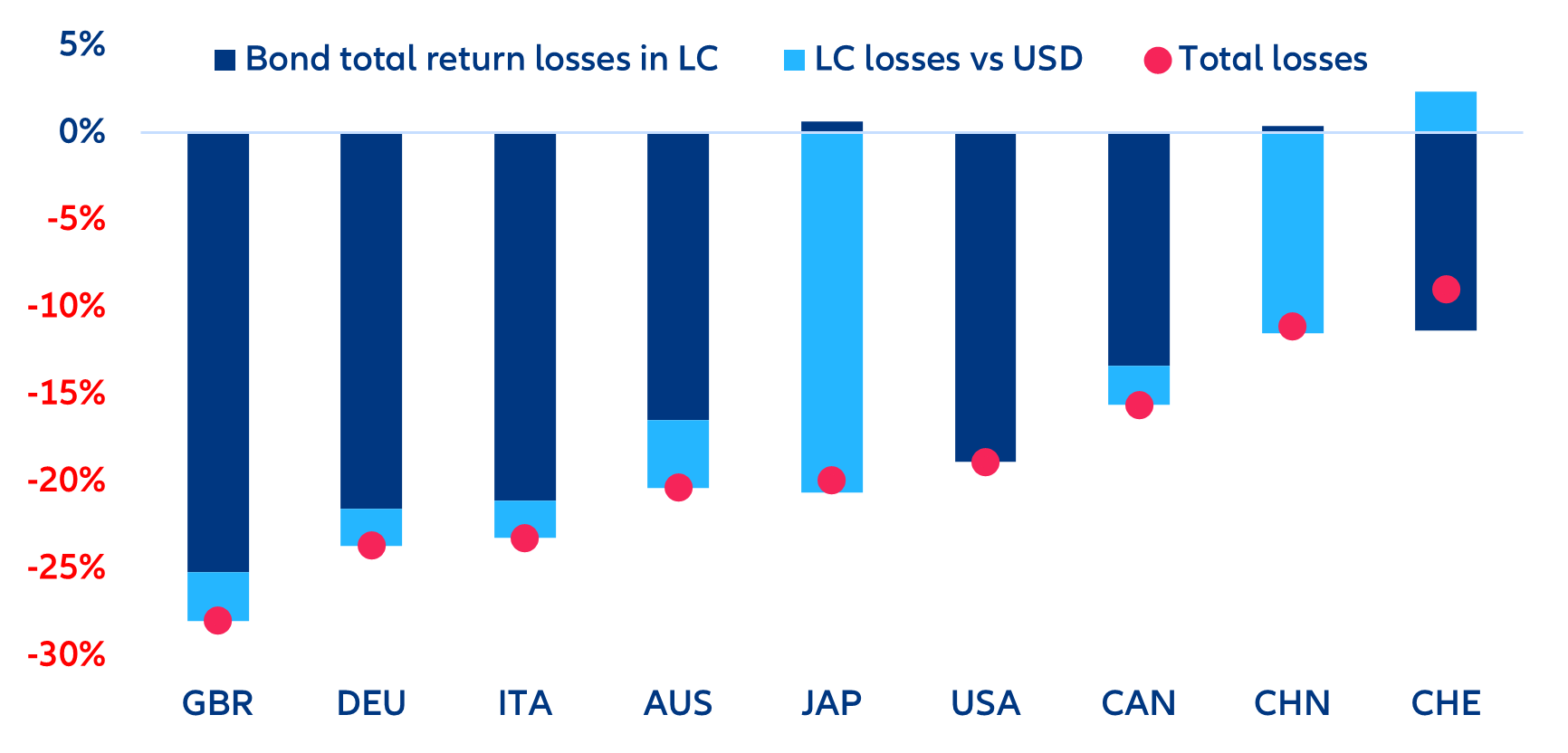

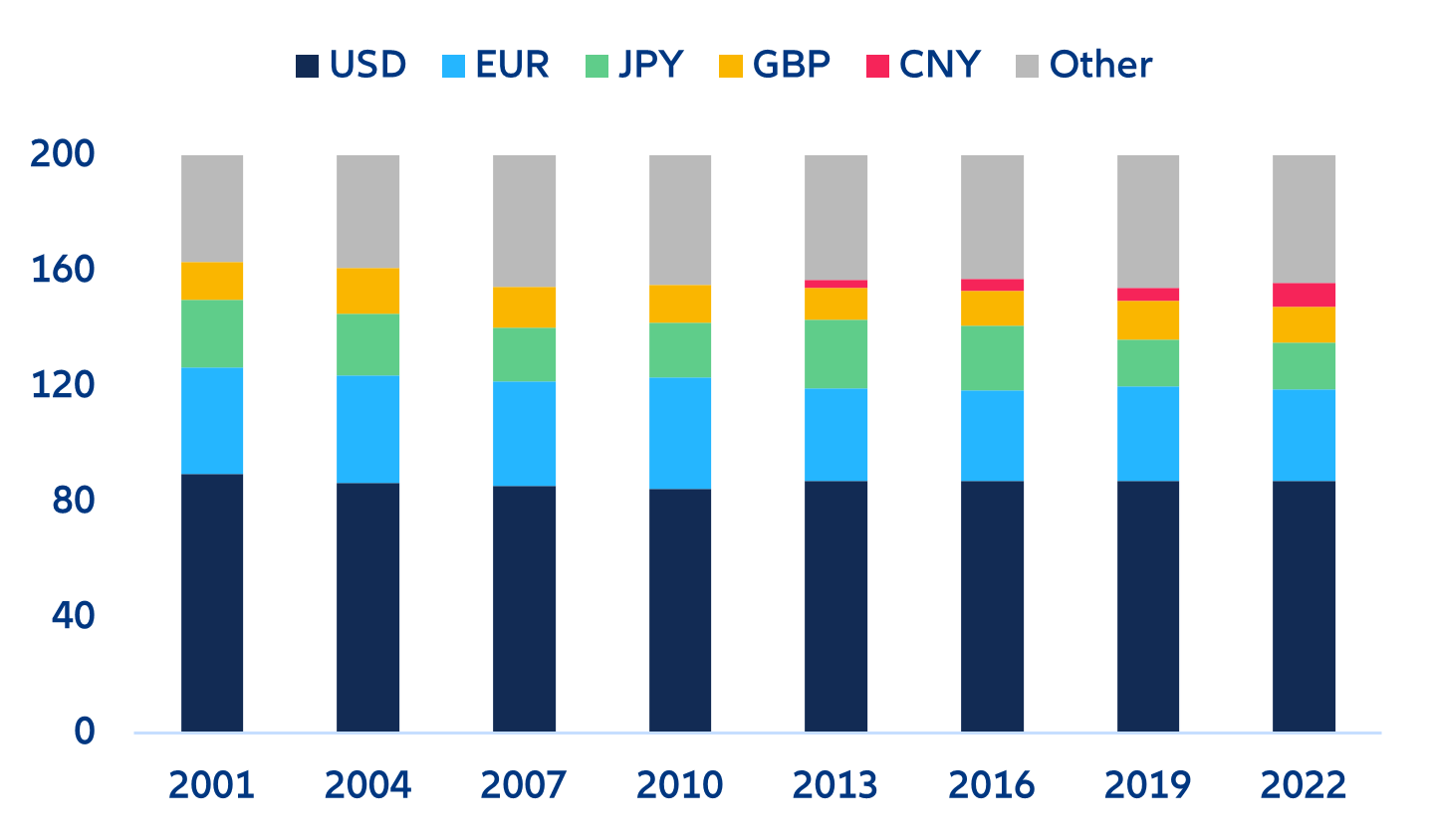

Recent efforts by some emerging markets (EMs) to diversify their currency reserves away from the US dollar have raised questions about the beginning of the end of USD dominance. However, the dynamics of the USD’s decreasing share in global currency reserves are far more intricate than official statistics suggest (Figure 12). The key factors often overlooked when discussing official currency reserves are that (1) any persistent change ultimately mirrors the currency composition of trade (rather than an ad hoc policy choice, such as the strategic positioning of the Chinese renminbi as trading currency) and (2) the currency choice depends heavily on the availability of liquid instruments in efficient markets (paired with legal certainty and effective governance). Both factors are likely to support the status of the US dollar as the world’s premier reserve currency for the time being. However, the rising share of alternative currencies in global trade and the deepening of EM capital markets will chip away at the dominant status of the US dollar over time, without causing a regime change.

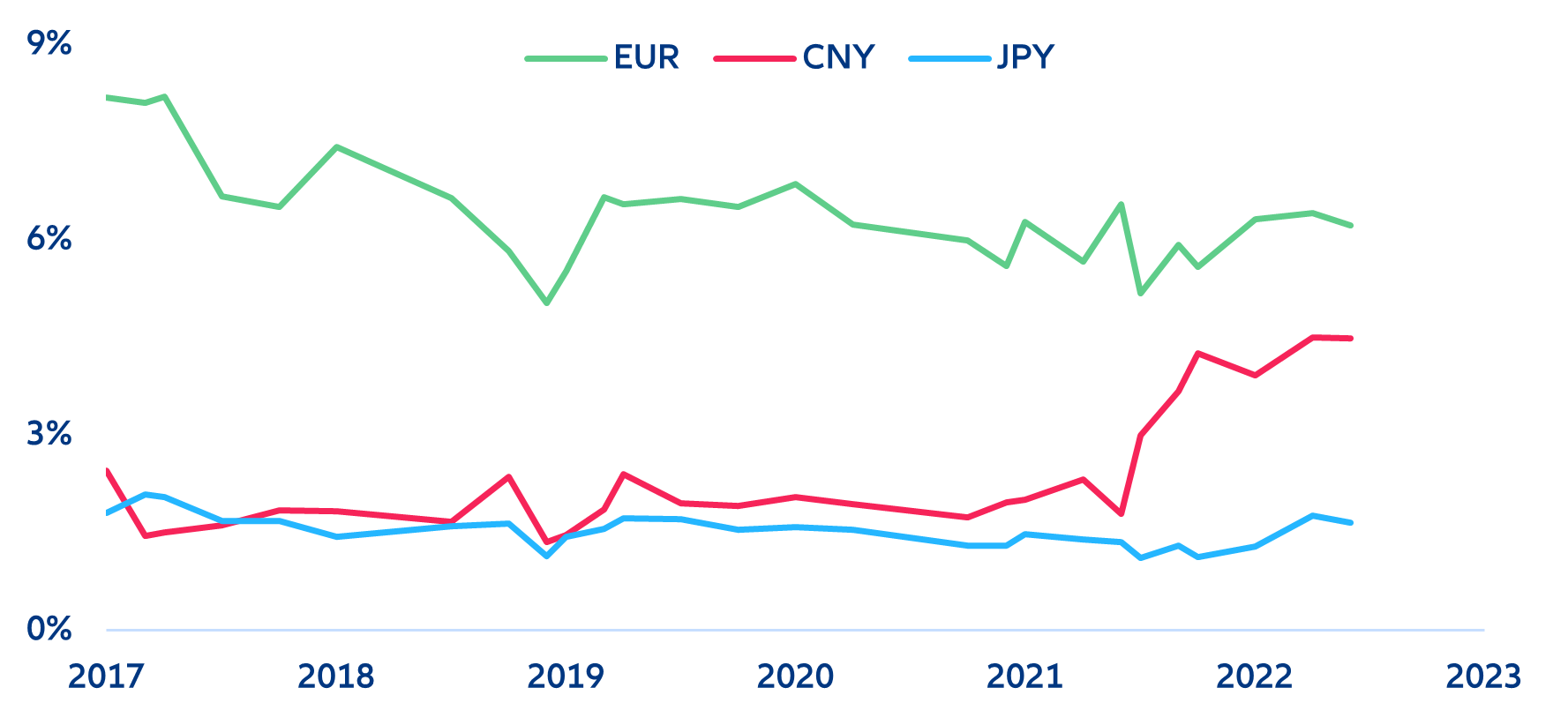

Firstly, the availability of liquid financial assets heavily influences the composition of FX reserves. The USD reigns supreme due to the depth and liquidity of its securities market (how most FX reserves are held), while other contenders such as the Chinese yuan (CNY) face challenges such as limited liquidity and accessibility. Additionally, the fragmented market of the euro (EUR) and the high degree of Japanese financial authorities' participation in the Japanese yen (JPY) market diminish their chances. When it comes to a hypothetical BRICS currency, many look at how the ECU or the SDR work, but the role that the USD has played or continues to play in their functioning is sometimes disregarded (Figure 13).

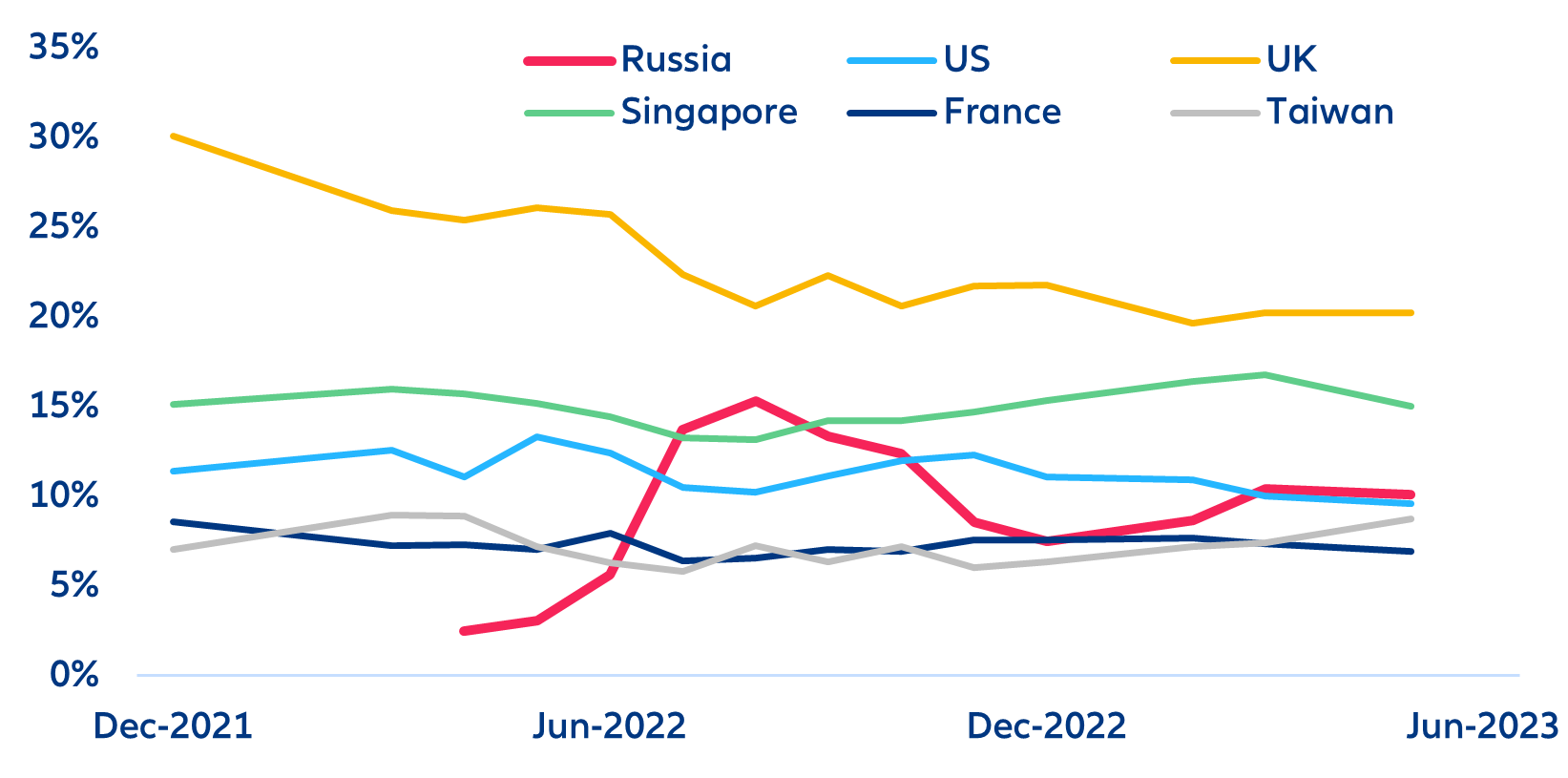

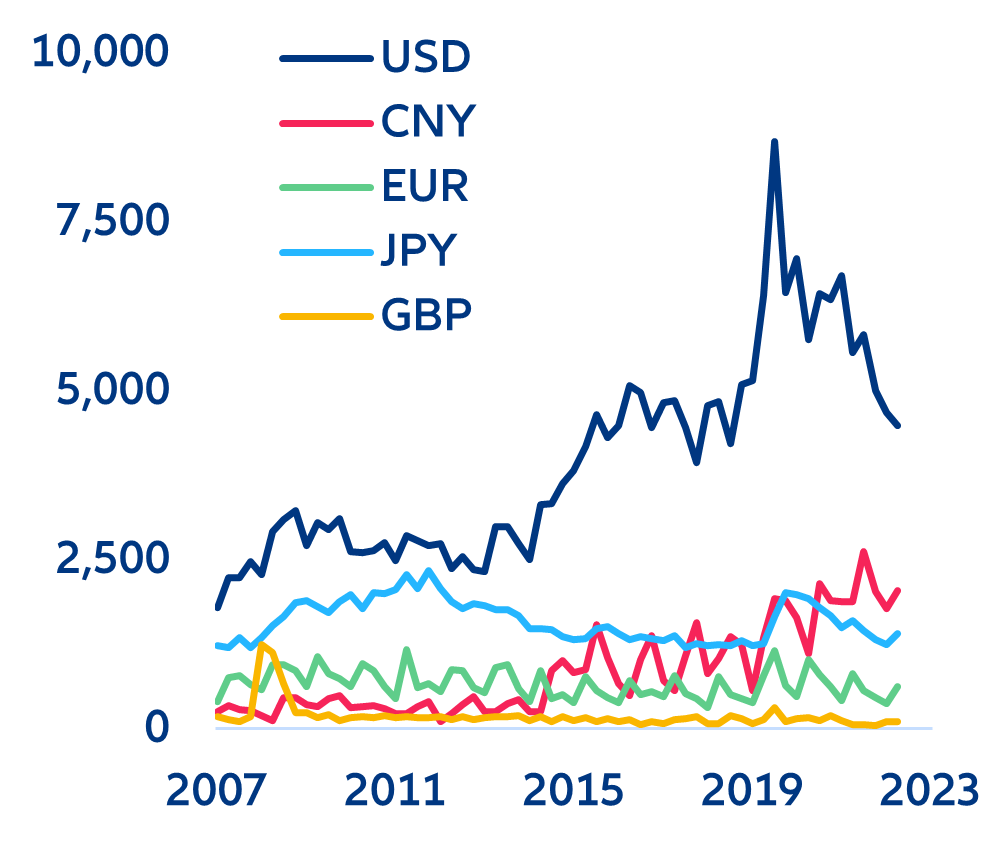

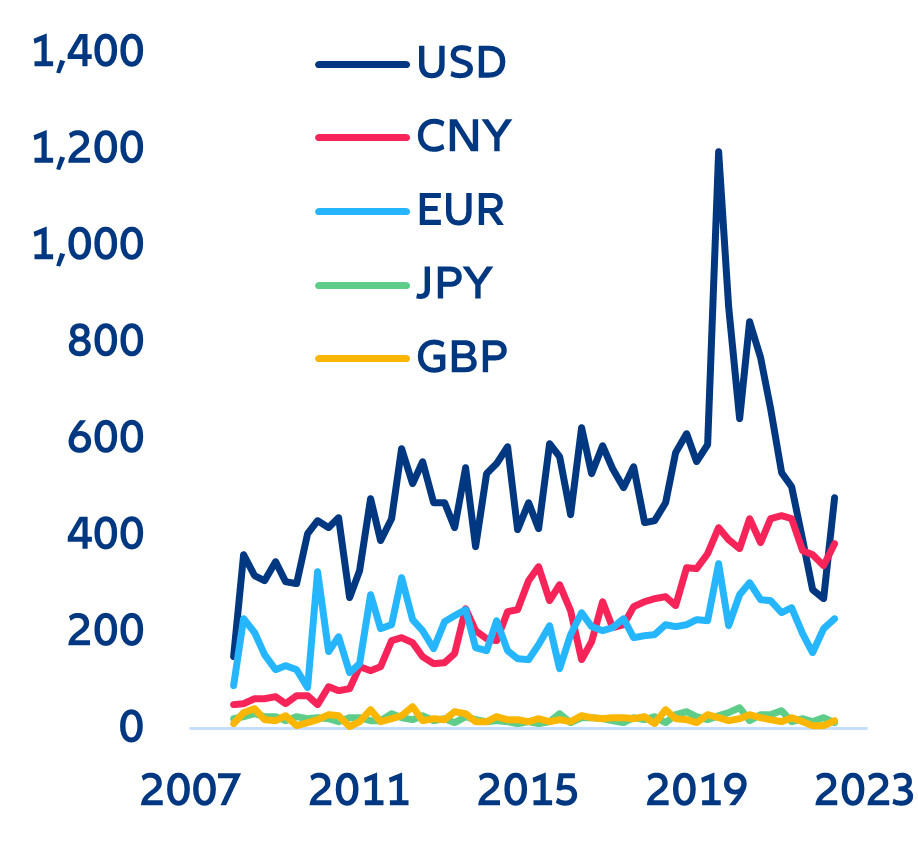

What will ultimately determine the USD’s role as reserve currency is not the portfolio allocation choice of central banks but rather the private sector’s use of the currency for trade and investment. Over the last decades, the position of the USD in private sector transactions has changed only slightly based on FX turnover (Figure 15), bond issuance by non-financial corporates and SWIFT payments (Figures 16 and 17). And while companies wanting to operate in Asia have been “forced” to participate in local currency markets, these currencies have yet to make a significant dent on the USD when it comes to raising money in international capital markets.

Over the near term, however, a stronger USD would weaken its role as reserve currency. If access to USD becomes more expensive, borrowers will search for alternatives. As USD reserves decline across many EM economies, they become more selective with its use, and try to fall back on local currency finance (e.g. “Liraization” attempts). If taken to the extreme, this situation would amount to a real-life test of Gresham’s Law in the era of fiat money.

Over the longer term, the incipient fragmentation of global trade and more diversified oil demand – if persistent – are bound to strengthen the case for USD alternatives, but any significant switch will take a long time to evolve. The structural change in the oil market brought about by the shale-oil revolution (which allowed the US to become energy independent) can paradoxically hurt the role of the USD as the global reserve currency since oil exporters, which play a crucial role in the USD status (oil prices, large shares of USD reserves), would need to re-orient themselves to other countries and their currencies. In addition, the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have led to a rethinking of globalization by both advanced economies (by creating more resilient supply chains) and EMs (by challenging the US dominance over the global financial system). Both developments have resulted in an incipient trend in the commodities market: some EMs have decided to use alternative non-USD currencies (typically CNY). However, a pivot to alternatives will take a long time due to substantial obstacles, especially when it comes to attracting foreign investment, which require a stable currency.