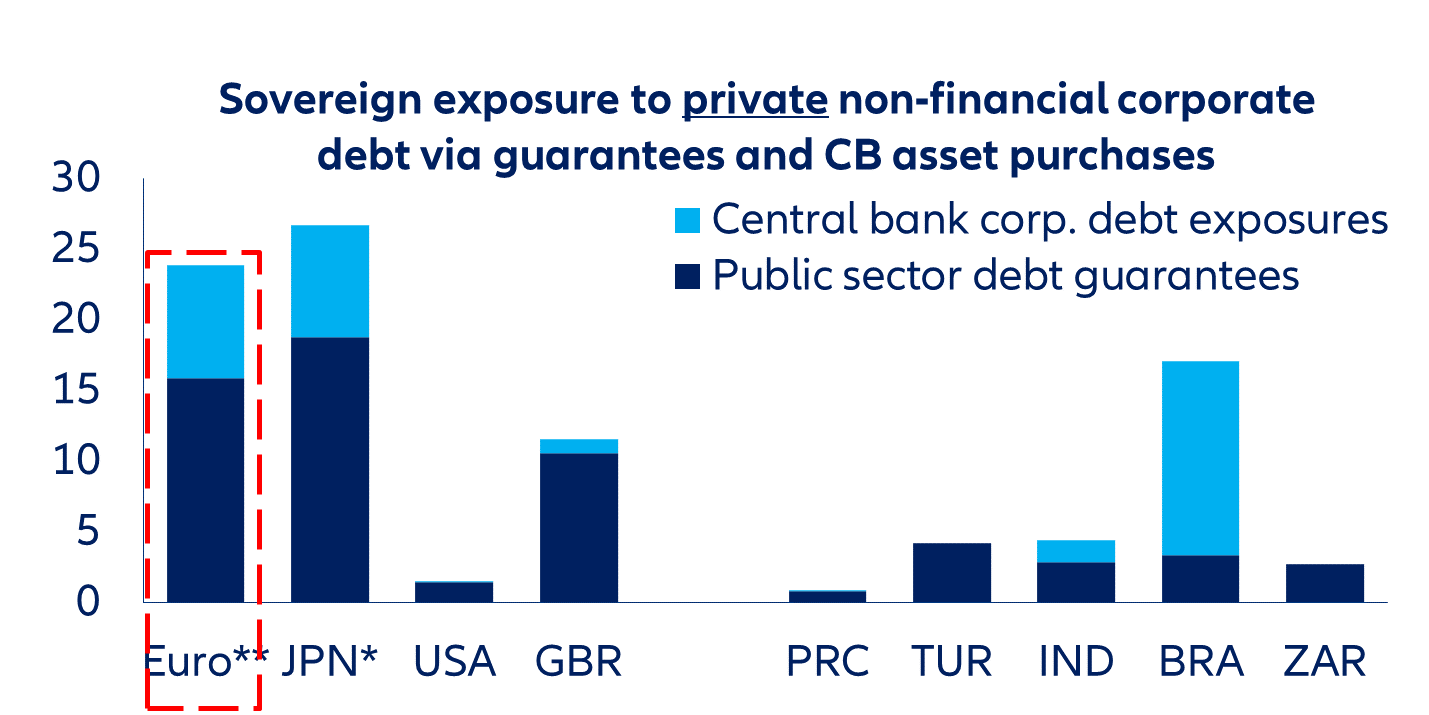

- Over the last four years, Eurozone sovereign exposures to the corporate sector have exceeded 20% of GDP. While support measures have helped keep vulnerable firms afloat, there has been considerable economic scarring – and the risk of higher corporate defaults continues to rise (especially as governments start tightening their belts). Higher public-sector exposures raise the risk of a doom loop as weak growth puts increasing pressure on corporate margins.

- Over the next few years, the Eurozone could become trapped by a combination of weak fundamentals and excessive policy interventions. This exacerbates vulnerabilities from mispriced risk, while underlying fundamentals continue to worsen. But as the credit cycle turns negative (with money supply having turned negative for the first time ever) and fiscal policies become restrictive, the economy must eventually “snap back” to weak fundamentals.

- In an extreme adverse scenario, the complex system of interlinkages between real activity, banks and sovereigns could trigger a fundamental repricing of risk in a new “doom loop”. If we conservatively assume default rates seen in previous crises, a cumulative corporate default rate of 10% over the next two years (up from less than 1% per year) would wipe out about three years of bank profits. Public-sector losses would amount to 5% of GDP on average from direct losses and foregone corporate tax revenues.

- While this scenario remains extreme, it underscores that financial sector policies need to be become more forward-looking, especially in countries where slower insolvencies and lower asset-recovery rates amplify economic scarring, threatening to undermine the financial system and eroding valuable policy space. Pre-emptive policies must also include completing the Banking Union.

In focus – A new Eurozone doom loop?

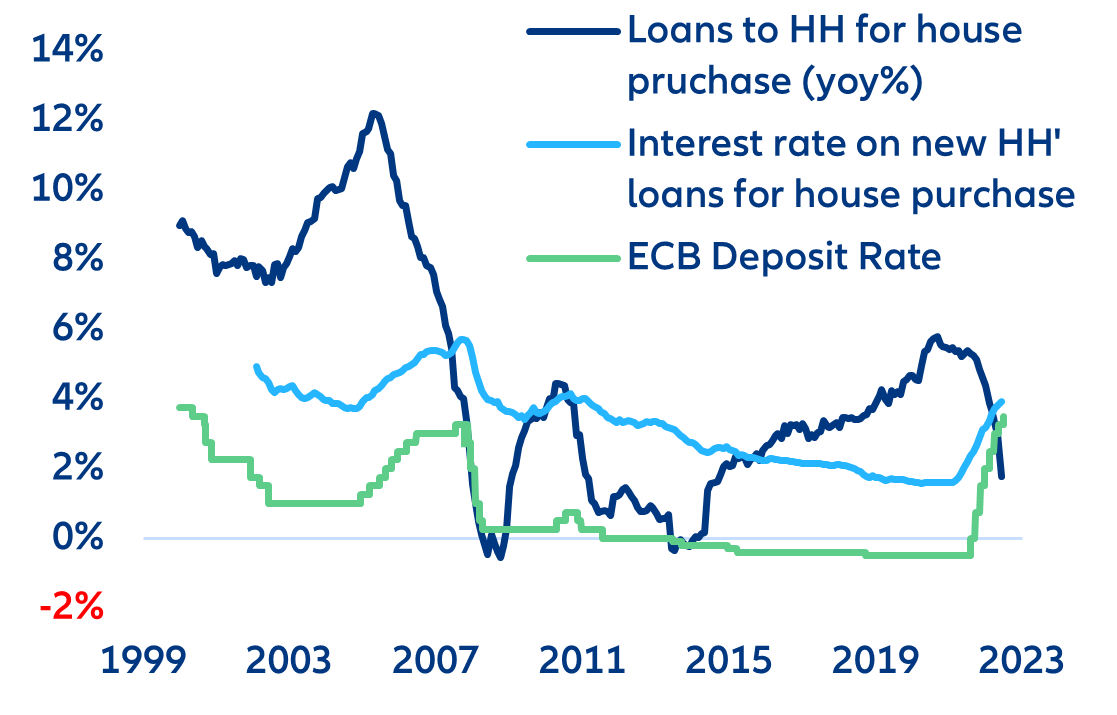

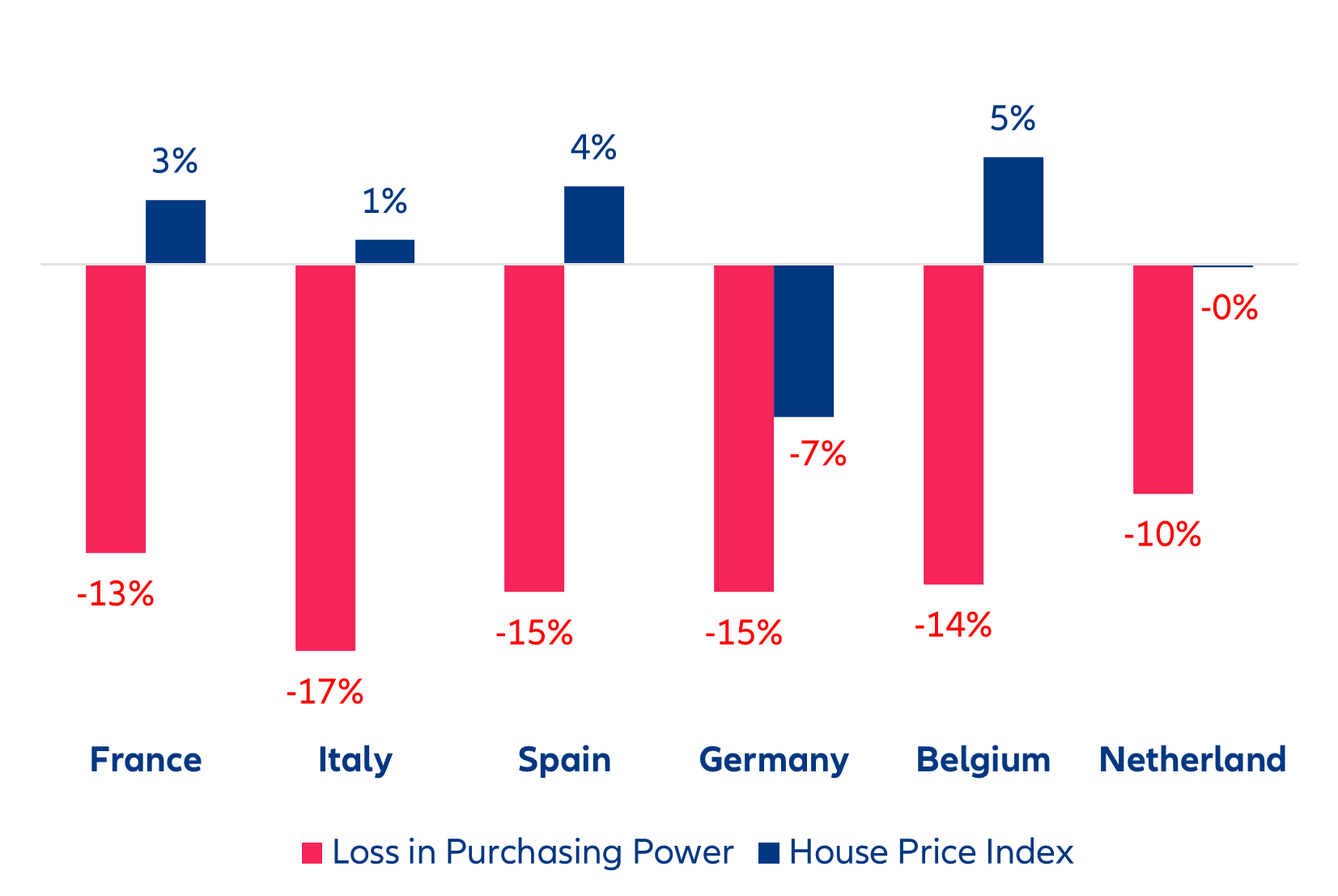

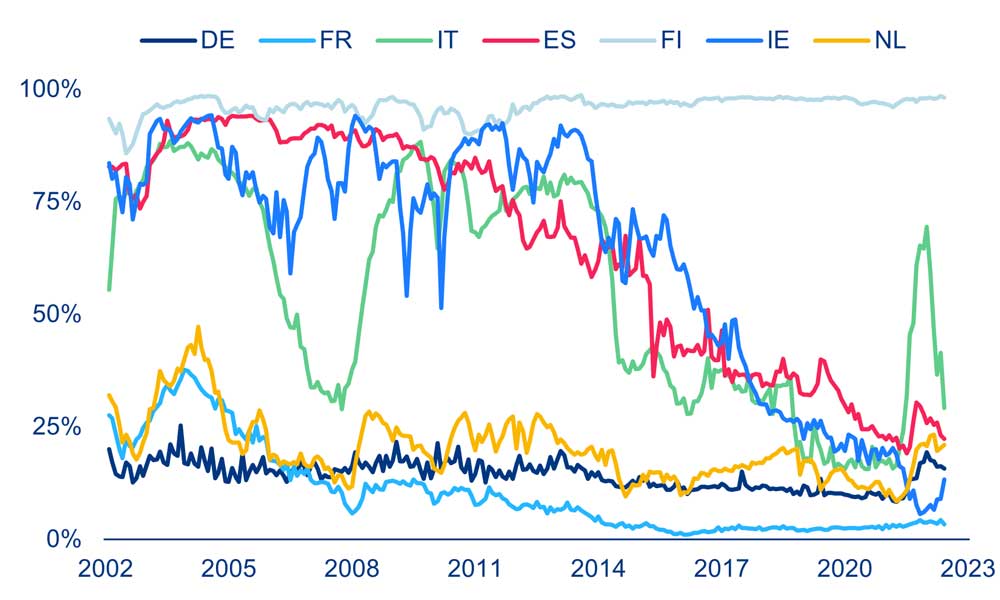

Eurozone housing market and home affordability – still too expensive

Even as the outlook for Eurozone housing prices is fraught with uncertainty, we do not expect consumers to fully recover purchasing-power losses – and the full transmission from market interest rates to mortgage rates is also still in the making. In 2024, wage-growth expectations (between +4% and +5% in 2023, and +3% and +4% in 2024 for the major economies) will recover only partially in real terms, and the expected home-price correction will fall short from the breakeven figures mentioned above in most countries. Moreover, the fact that fixed-rate mortgages became more popular across almost all the countries has prevented a full pass-through to mortgage rates. But this will come as many mortgage rates are fixed for only a specific period of time. As such, we expect home-affordability losses to range between 5% and 12% by 2024.

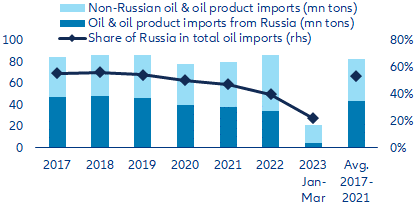

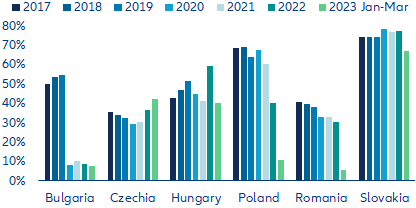

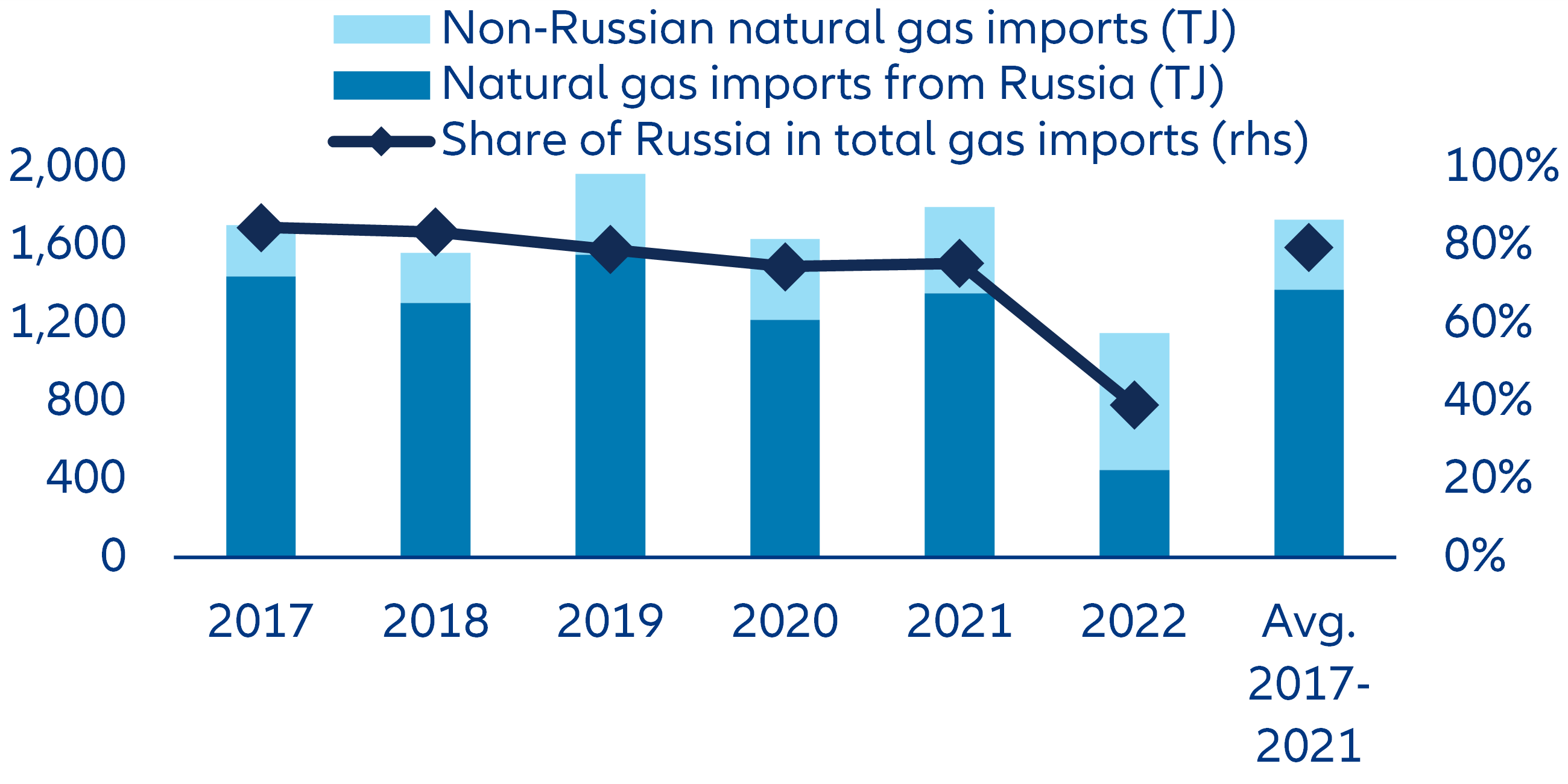

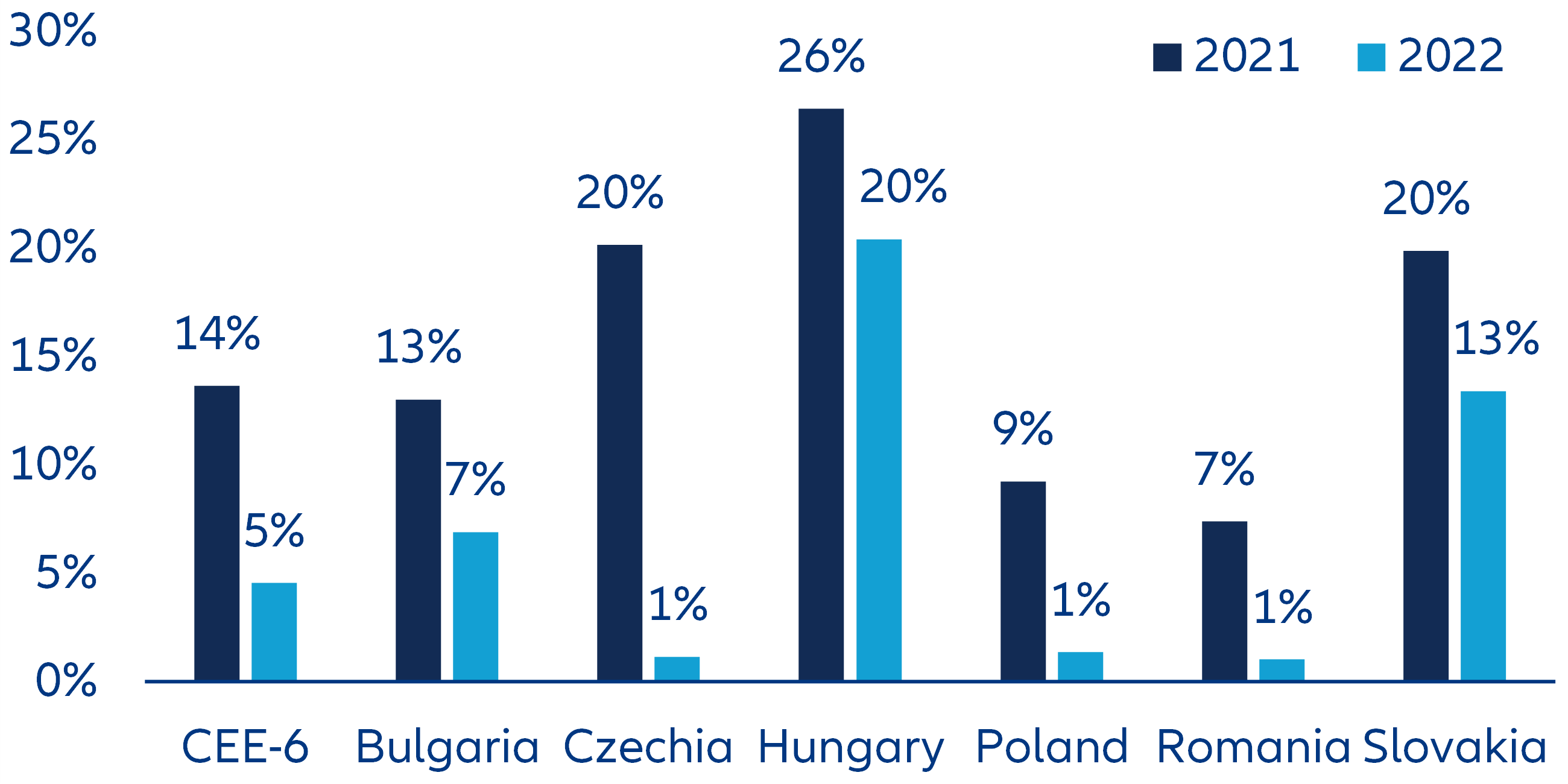

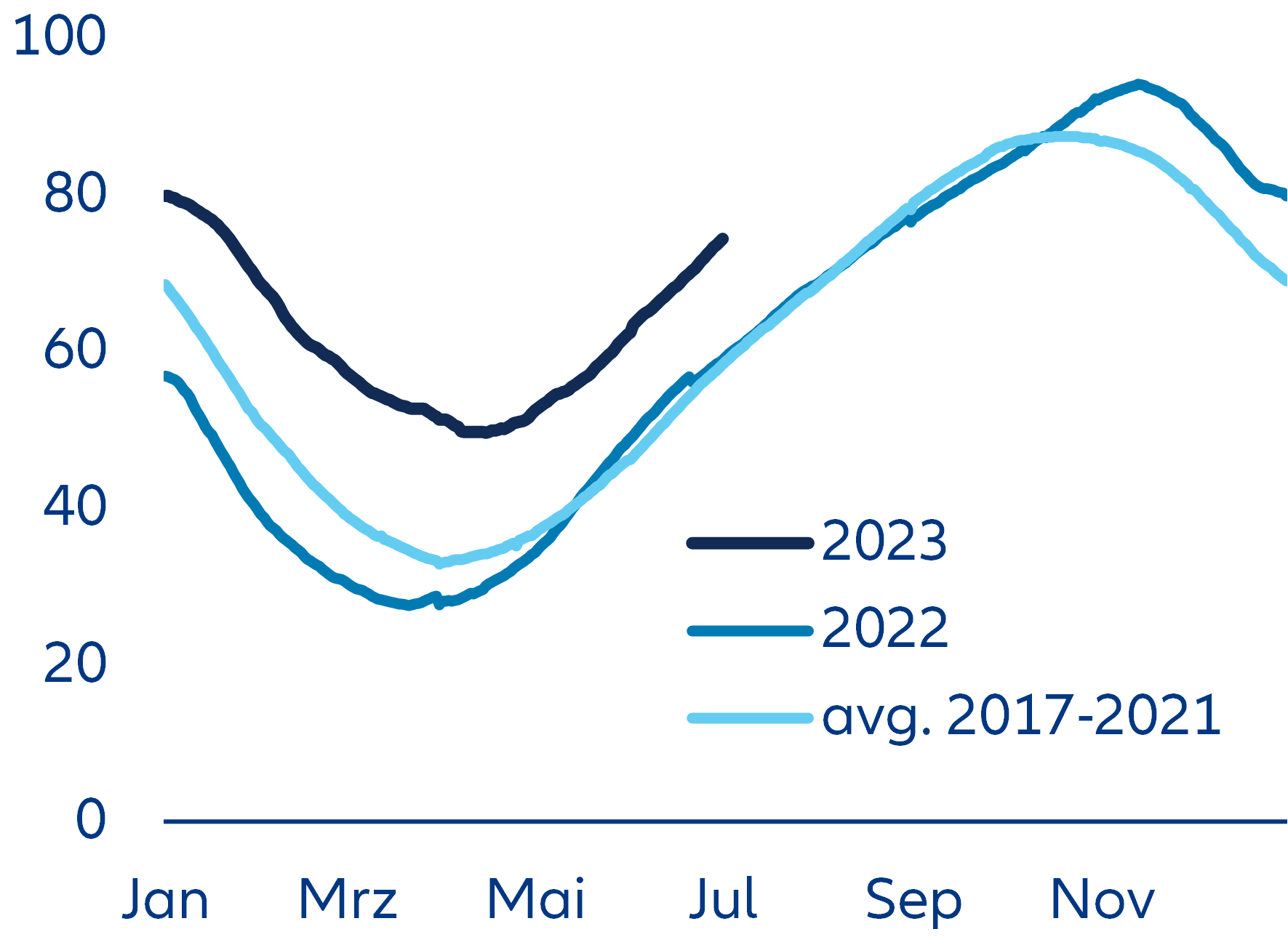

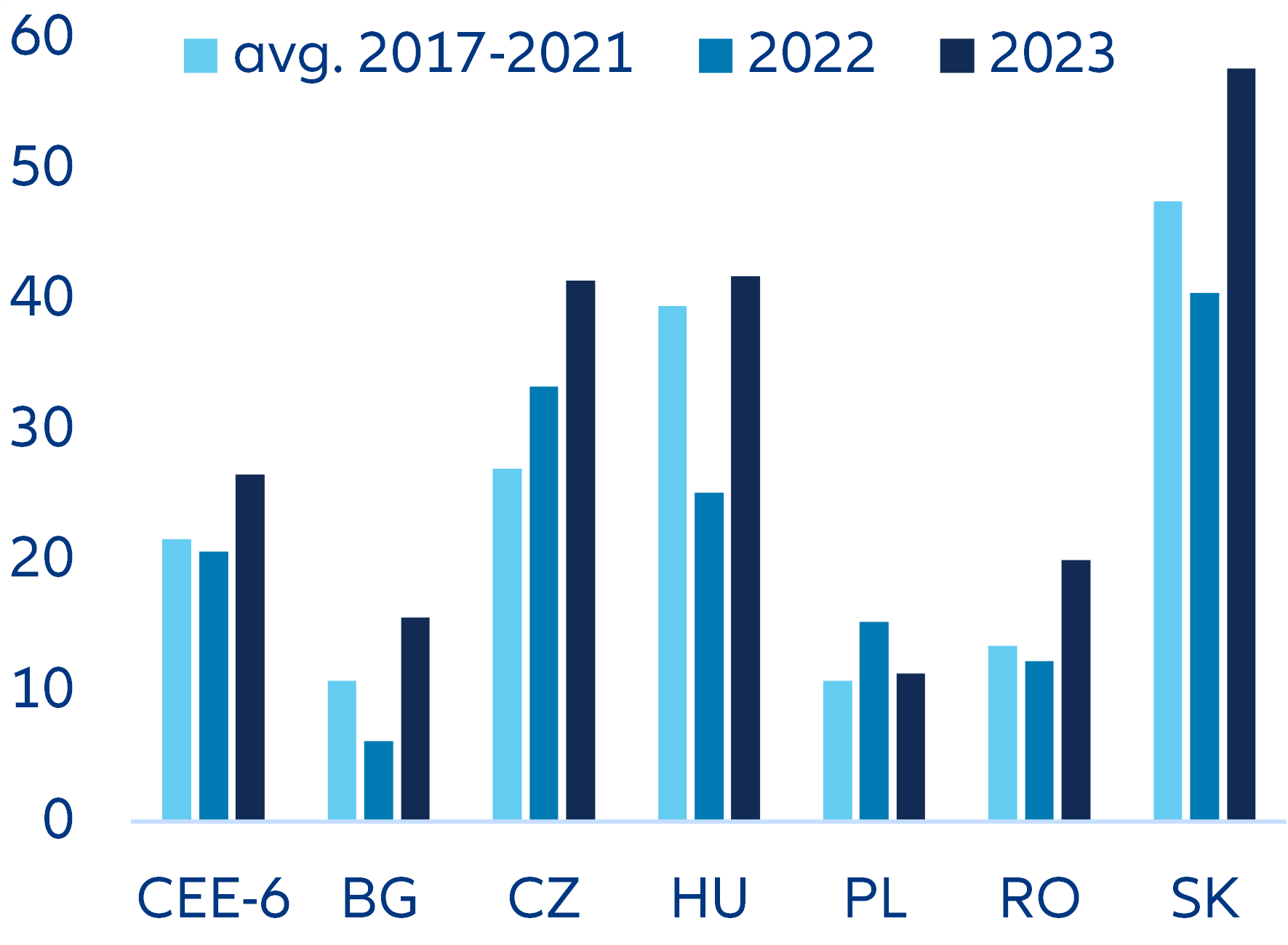

Central and Eastern Europe – Energy crisis unlikely next winter, thanks to declining dependence on Russian oil and gas

Simultaneous currency depreciation and subsidy cuts – igniting social unrest in Africa?

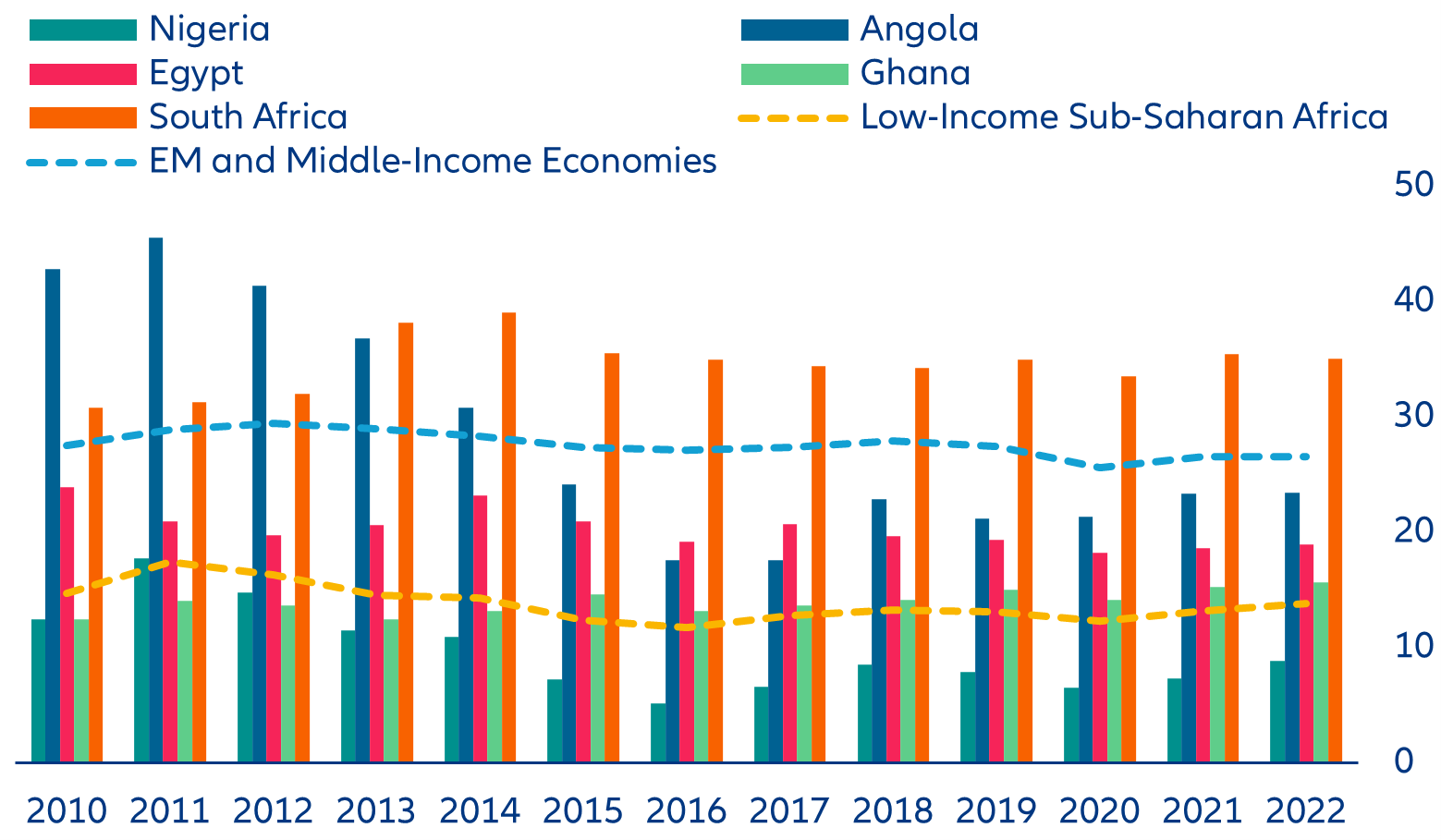

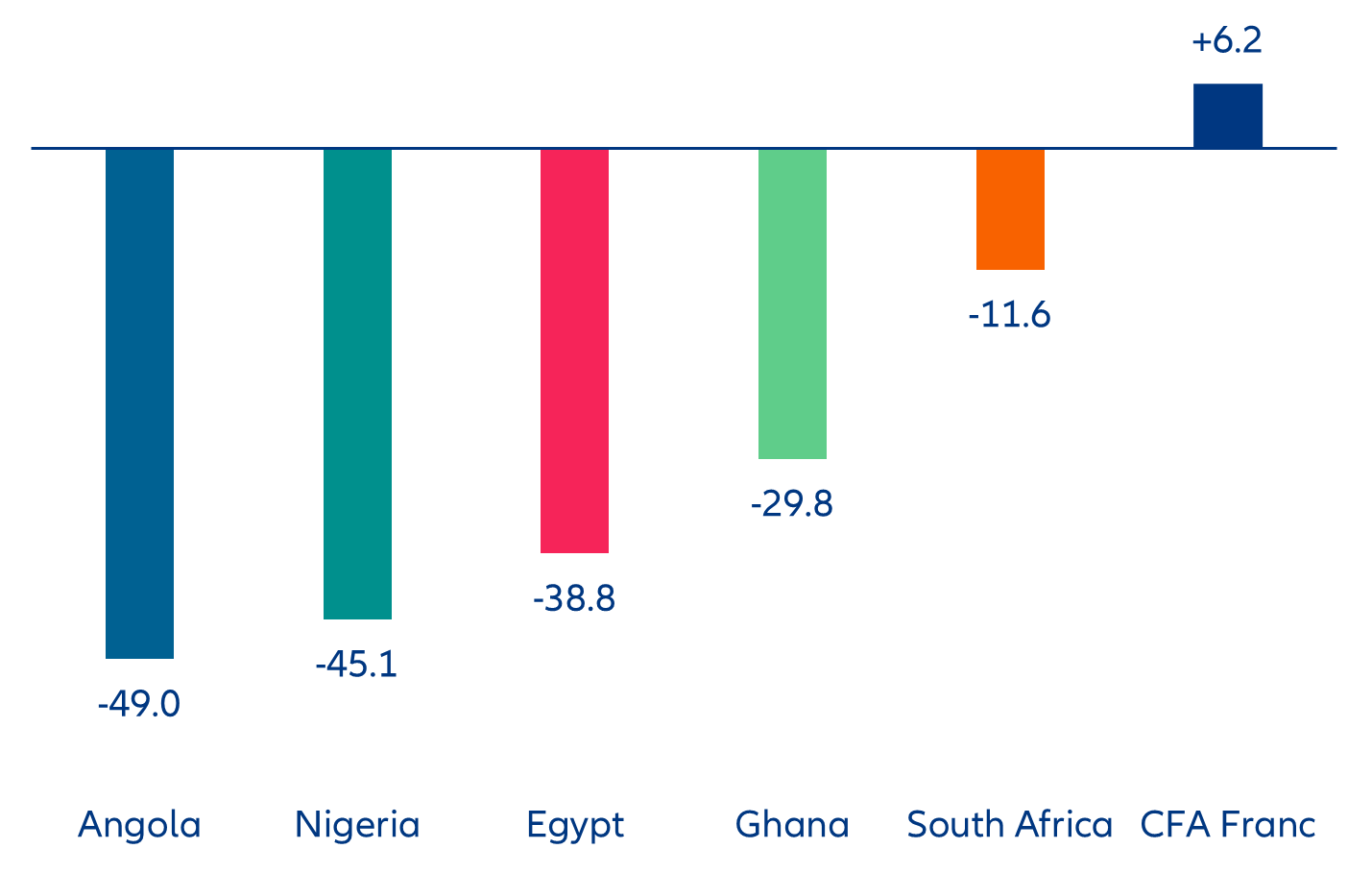

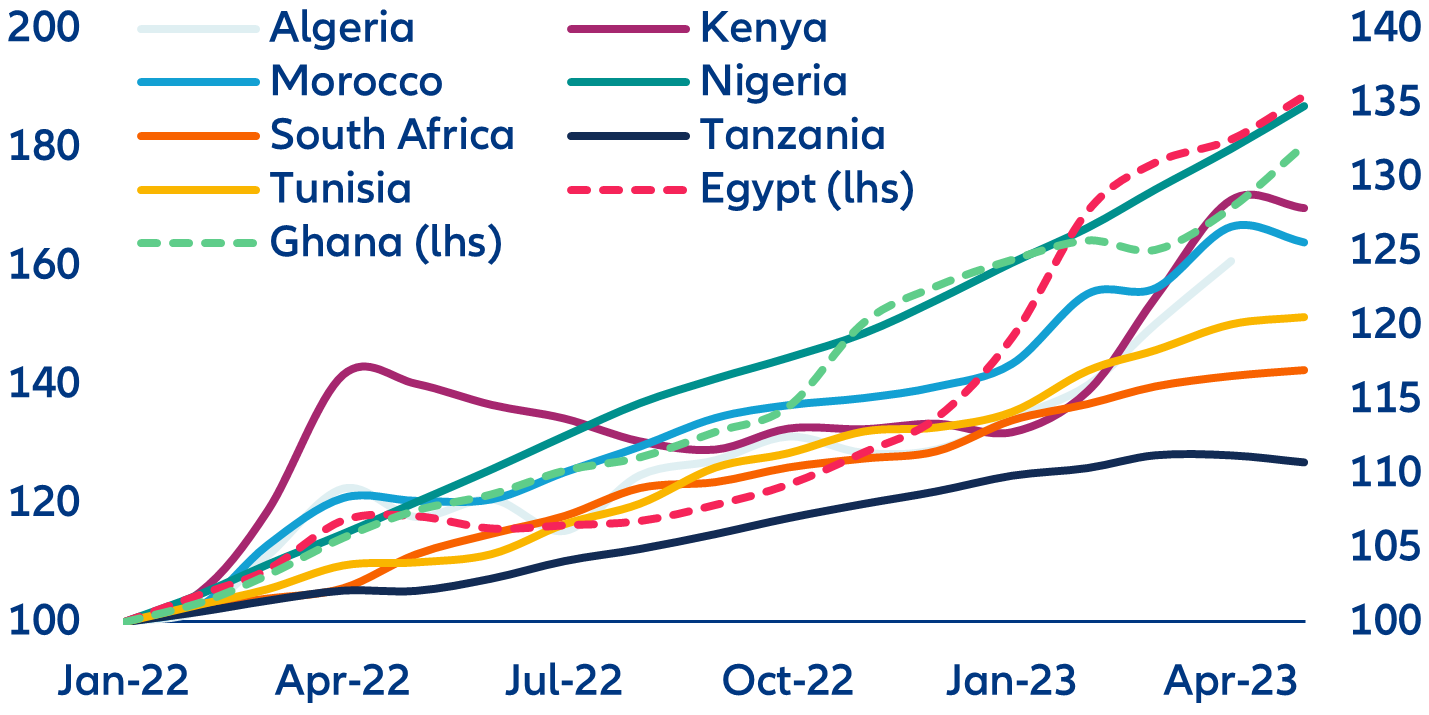

40% of the African economy faced a local currency devaluation of at least 30% in the past 12 months. It means that at best the cost of imported goods (in terms of units of local currency equivalent to the same amount of USD) has increased by 40%. The fact that inflation has not risen as much (we forecast an average inflation rate of 15.9% on the continent for 2023) tells how much of these costs have not been passed on to the population yet as well as the magnitude of government subsidies, such as those on fuels, which historically are imported even by major hydrocarbon exporters, like Nigeria and Angola.

Along with devaluation, the removal of fuel subsidies adds up to the loss of purchasing power and to enterprise costs. Two months ago, the IMF published an analysis on currency depreciation across Sub-Saharan Africa, pointing to the vulnerability of economies to the international economic situation as the main cause and suggesting tighter monetary policy, fiscal consolidation (e.g., eliminating fuel subsidies) and strengthened social safety nets as countermeasures in light of historically low government revenues (see Figure 9).

The combination of devaluation and subsidy removal may trigger significant unrest across the region; Nigeria and Egypt, the continent's two largest economies in terms of GDP, have shown similar dynamics in recent weeks despite a different political setting. Nigeria comes from a presidential election in February in which the winner, Bola Tinubu, was voted by 9.4mn people out of a population of around 231mn. In Egypt, a presidential election is due early next year with President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi looking to repeat the success of 2018 when he got 97% of the vote, or 23mn votes out of a population of 97mn at the time. An escalation of social tensions could have a contagion effect on institutional strength and stability in the area also due to uncertainties about Wagner paramilitaries' role and ongoing conflicts.

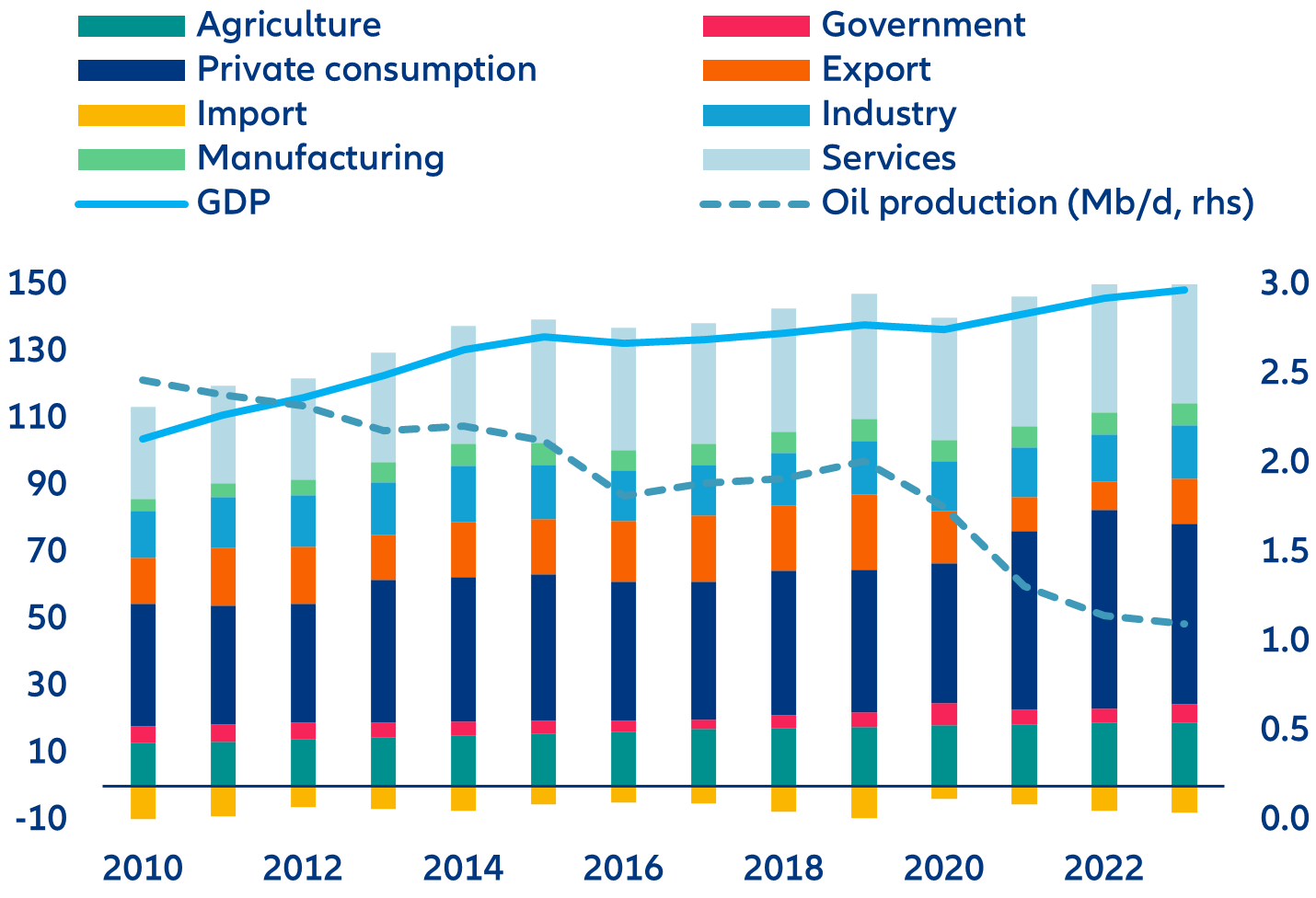

Nigeria can be seen as a microcosm of Africa with its strong demographic dividend and great political fragility, deep divisions between north and south and along cultural and religious fault lines, a post-colonial legacy still visible in the balance of trade and an increasingly worrying level of public debt. Struggles to convert economic potential into real growth, production limited by instability and insecurity (as in the case of oil output remaining below the OPEC-agreed quota) and economic diversification still in the making suggest that developments of recent weeks may tell us much about what lies in store for the entire region, for better or worse.

Nigeria’s new administration delivered a combo of measures in a fortnight, such as the removal of the fuel subsidy that brought gasoline from USD0.55 per liter in April to USD1.1 by end-May, and the devaluation that came in on 14 June. Two weeks after President Tinubu assumed office, the second longest-serving governor of Nigeria’s central bank was put under arrest. Under his tenure, the central bank supplied the government with the equivalent of USD49bn (NGN22.7trn) in the form of advances, de facto increasing domestic public debt and reducing local currency supply, under a clause that can be activated only if the government experiences a temporary revenue shortfall. These claims will also be subject to devaluation, helping the government repay at least partially such exposures through oil revenues in hard currency. The devaluation could thus help rebalance the public debt profile, but it will bring along prolonged inflation, a higher import bill and additional stress on banks. Short-term domestic debt accounts for more than half of the total, with two-year interest rates well in the double-digits. Assuming that the devaluation could help reduce sovereign exposure and make foreign investment more attractive, Nigerian banks may face a marked deterioration in the quality of assets, capital adequacy and the share of non-performing loans.

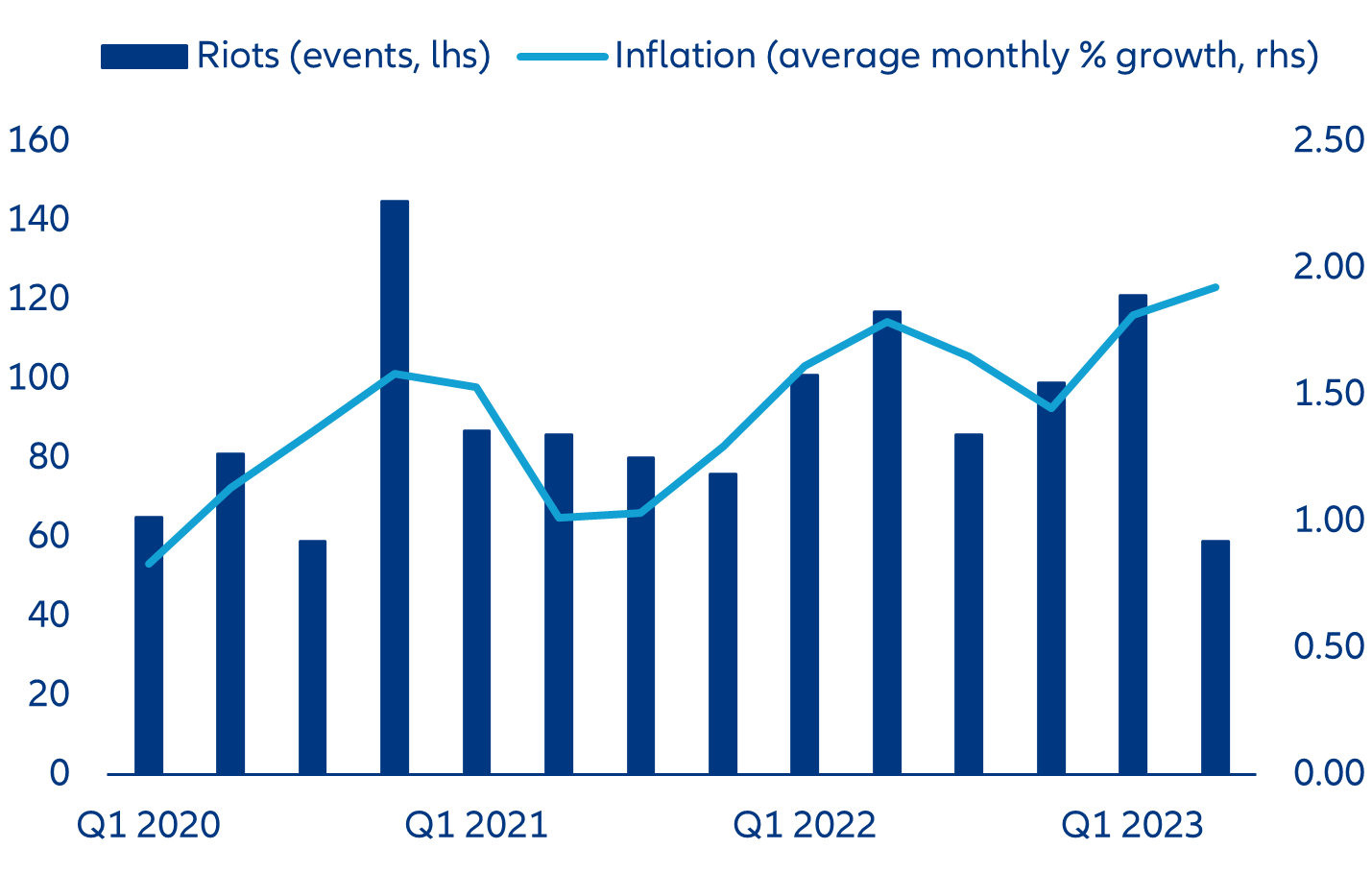

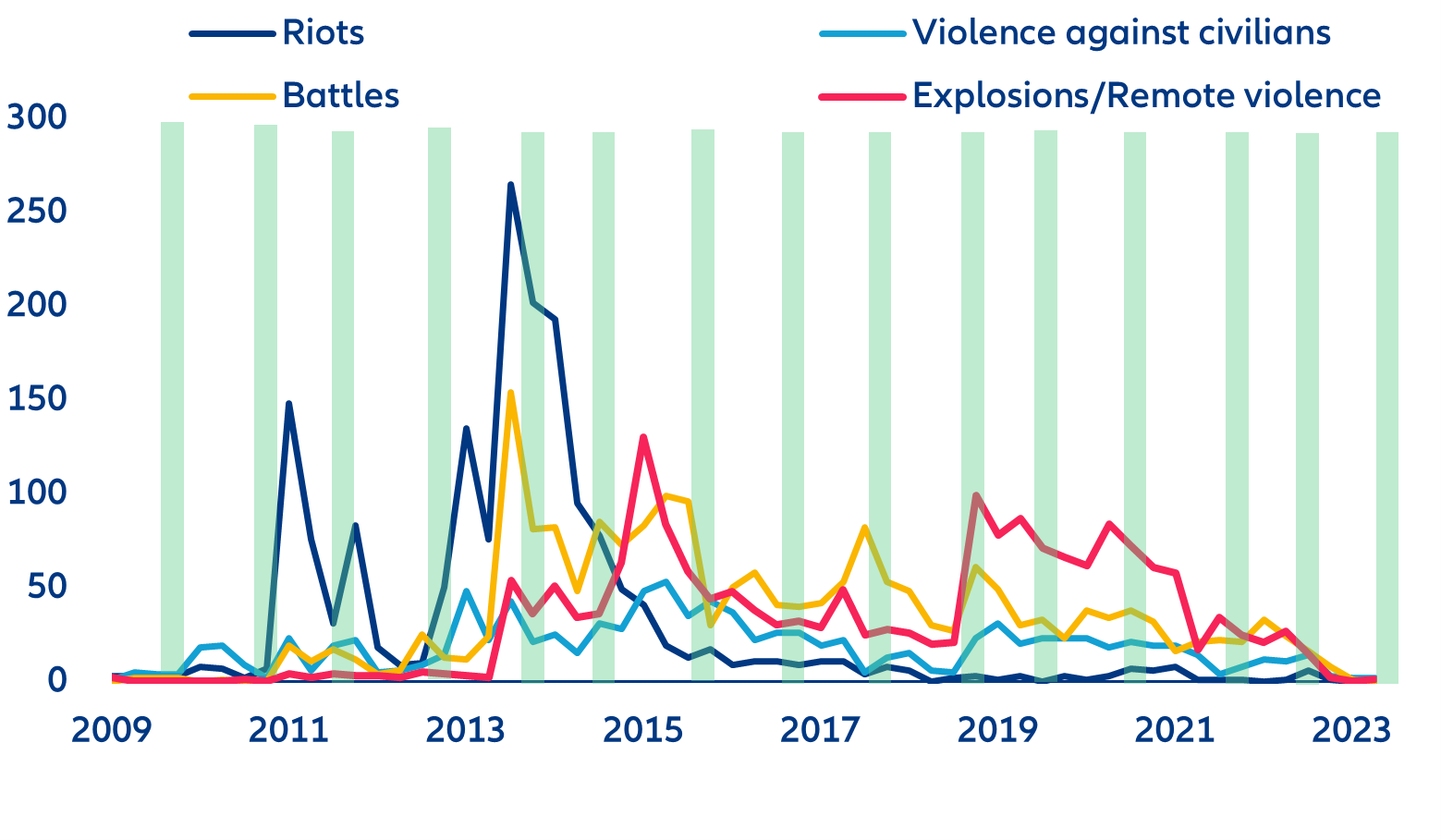

The shock therapy is aimed at redressing structural imbalances but may come with an elevated social cost as four out of 10 Nigerians live below the national poverty line and the minimum wage is still at USD65 per month, equivalent to around one tank of gasoline after the removal of the subsidy. In this context, social calm has been surprising over the past quarter given that unrest is significantly correlated to inflation (Figure 12).

The frequency of political-related events in the last quarters suggests that restrictions on public space have been extended beyond Ramadan, when confrontations historically tend to calm down (Figure 14). Since mid-2018, Egypt’s civil society has been de facto silenced and it is unclear whether this will lead to any resounding developments in the short term. The last time the calm lasted so long was in 2009-2010, i.e., before the Arab Spring erupted. Riots occurred often between 2011 and June 2014 (when al-Sisi's presidency began). In contrast, in the year before he came to power and ever since, explosive attacks and border and insurgent clashes have been by far the most recurring event, unusual for a country not involved in open conflicts. What is surprising about the past six months is the neutralization of any public action, be it a small sit-in or a militia clash. On the other hand, the escalation of the conflict in Sudan, sporadic Islamic State attacks on the Sinai Peninsula in the first half of 2023 and Israel recently complaining about the porousness of Egypt’s borders all point towards increased instability and limited military capability.

The distance between the establishment and the rest of the Egyptian population has also increased, although generalized unrest remains unlikely in the short term and progress towards IMF-inspired reforms is faltering. The IMF wants to ensure that conditional funds will effectively redress imbalances. Reforming the economy will require redesigning the role of the military and downsizing megaprojects (e.g. the new administrative capital 30km outside the overcrowded and increasingly impoverished Cairo) that are propping up the construction sector, which employs 13.8% of the labor force – third sector in Egypt behind agriculture and trade, second in terms of male workers. However, there is little incentive to pursue additional reforms with the upcoming presidential election in February 2024 and evolving bilateral relations with the Global South. For example, India is set to acquire a dedicated land area for national industries in the Suez Canal Economic Zone and build a USD12bn green hydrogen plant. Since its completion 154 years ago, the Suez Canal has been used as a strategic trump card by successive governments. Several sources talk openly about the possibility of leasing it. Transit fees were already raised several times in 2022-2023 and shipping brokers agree that there is still room for an increase without significant consequences on traffic volumes, given its competitive advantage over alternative routes.

The combination of silenced dissent and increasing mistrust towards international lenders leaves the door open for different outcomes, while another Egyptian pound (EGP) devaluation appears imminent. The differential between the nominal value of the EGP and its fair value is reaching another peak following those of late 2022 and early 2023. With several other countries on the continent devaluing their national currencies inter alia to attract investors, this could be the Egyptian government's next move, hoping the status quo holds up.

Unlike the sovereign debt crises, an escalation of social tensions could have a contagion effect on several African countries, also given the uncertainties about the role of Wagner paramilitaries in the area and increasing insecurity. While everyone's eyes have been on the state of African governments' accounts and the risk of transmitting sovereign crises for months, the main risk to the continent may instead lie in social risk, not economic or financial risk. No other sovereign defaults have emerged at the time of writing since Ghana's deafening crisis in December 2022, although public finances have been deteriorating in Egypt and Tunisia in particular. Several African governments are looking for their own way out with lenders (concessional lenders, China, former colonial powers, other African governments). Three years after a currency crisis, real GDP is typically between 2 and 6 percentage points lower than where it should be based on long-term growth. In most cases, however, output losses start materializing before the currency collapse takes place. In fact, it turns out that the collapse of the currency itself boosts production. Previous research shows that output growth slows down in the year leading up to currency devaluation and during the same year. However, the likelihood of a positive growth rate in the year of the collapse is over two times more likely than a contraction, positive growth rates in the years that follow currency collapse are likely and the persistence of the crash matters. Instead, it will be the responsiveness of individual economies and the resilience of the social contract that will tell us whether a cost-of-living crisis will also bring social disruption across the region.

In focus – A new Eurozone doom loop?

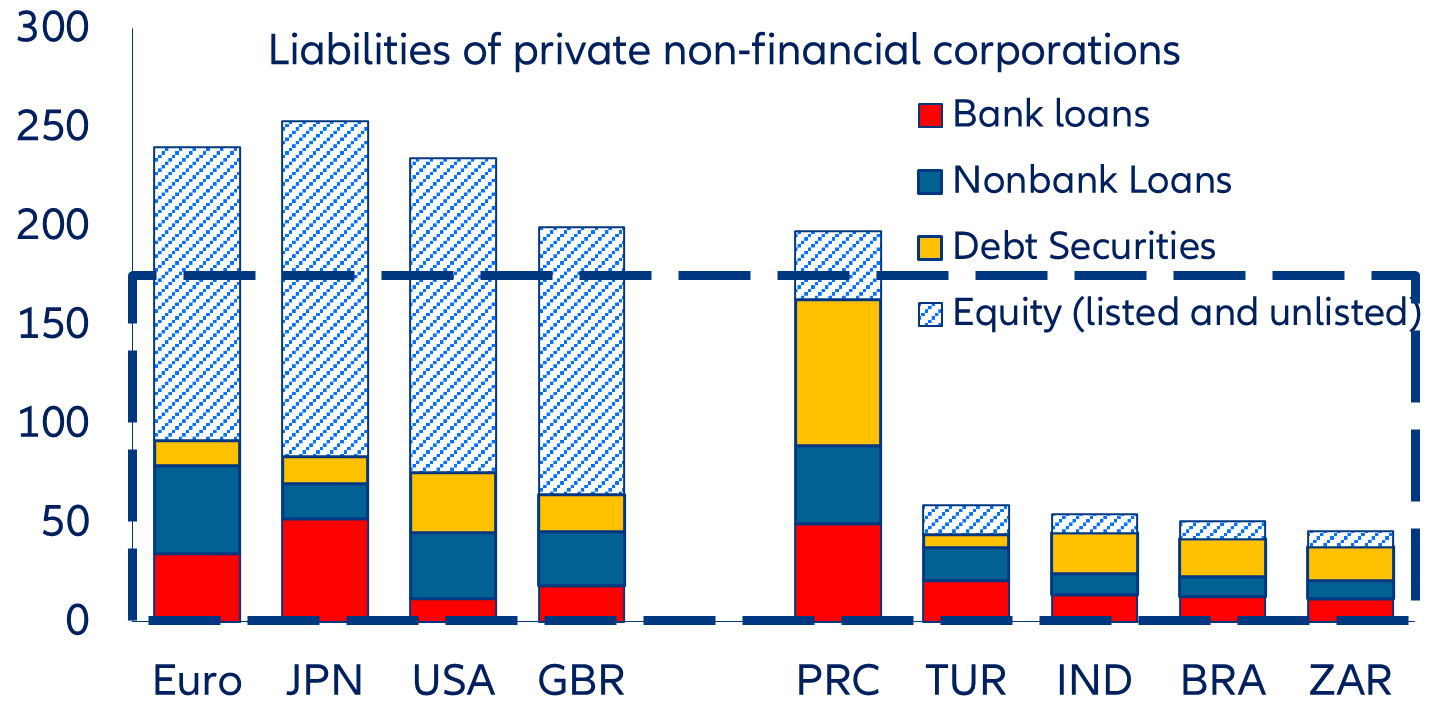

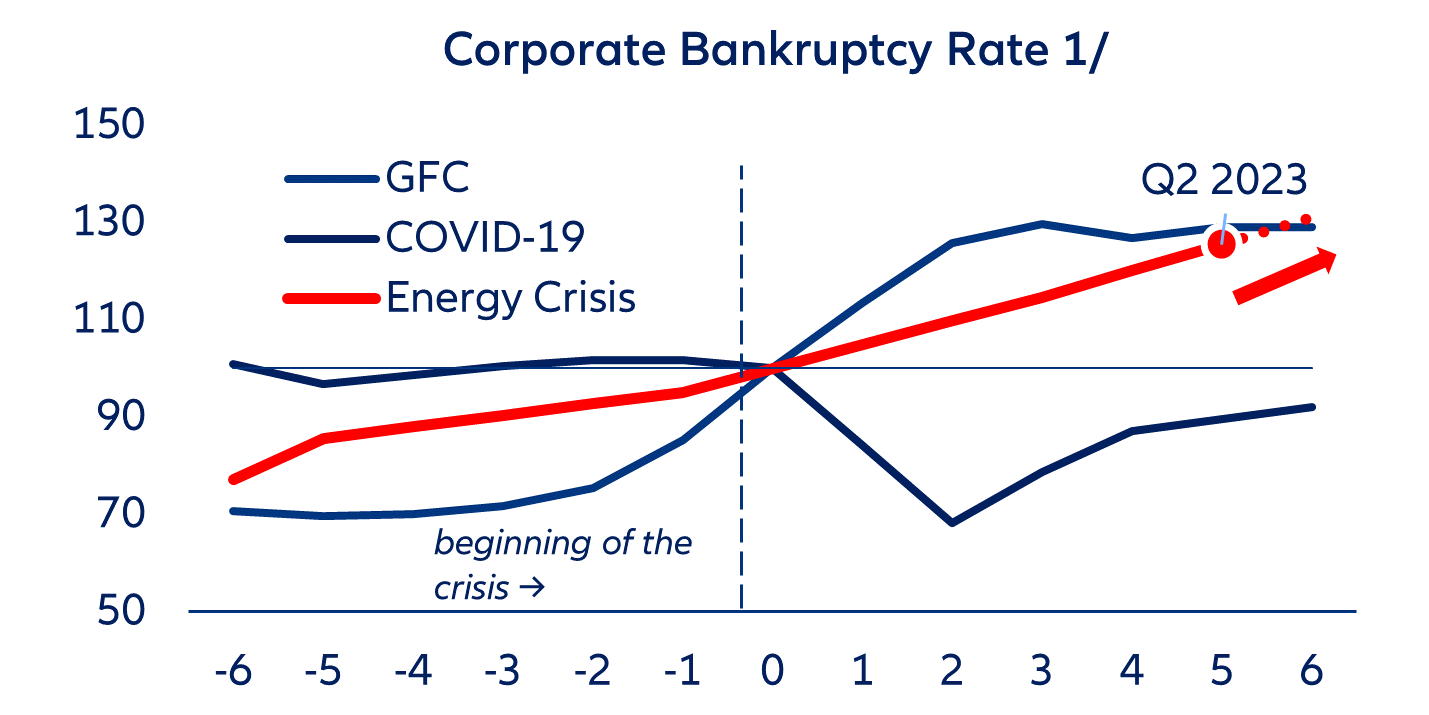

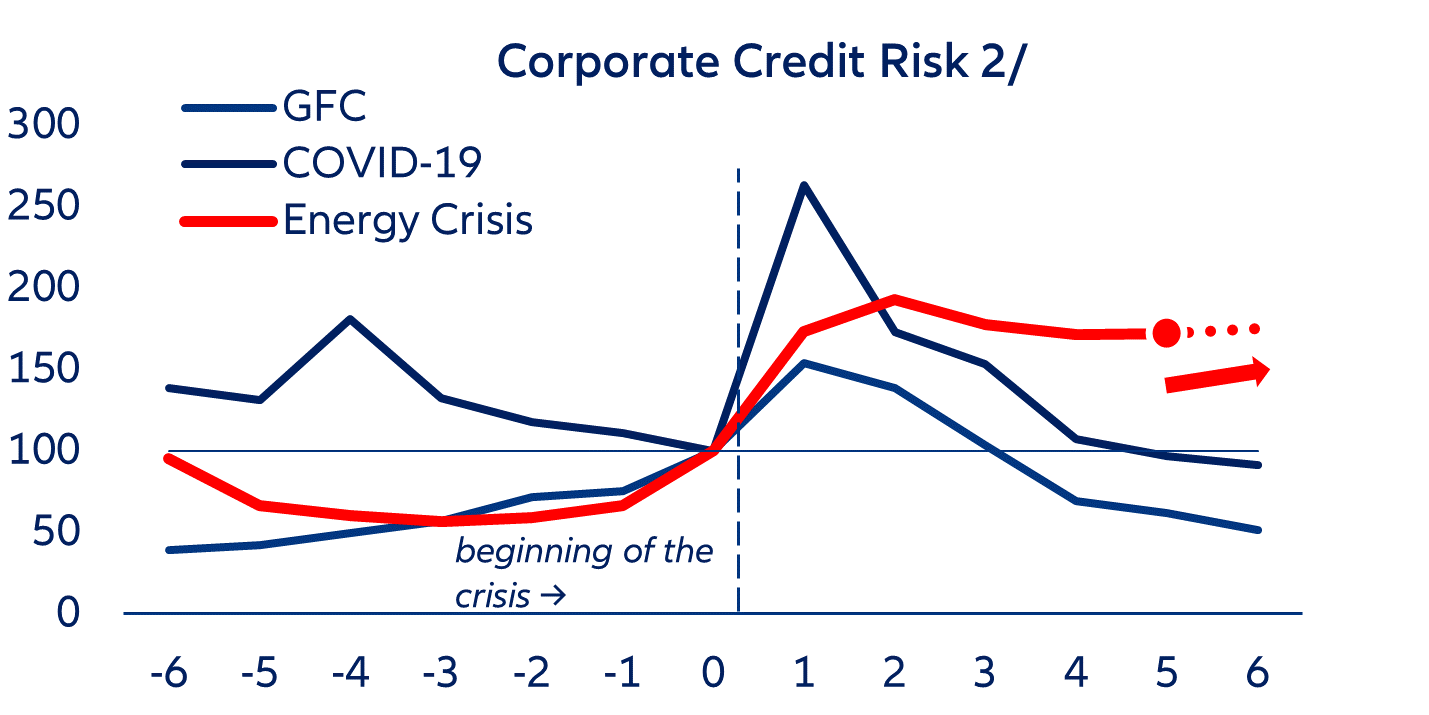

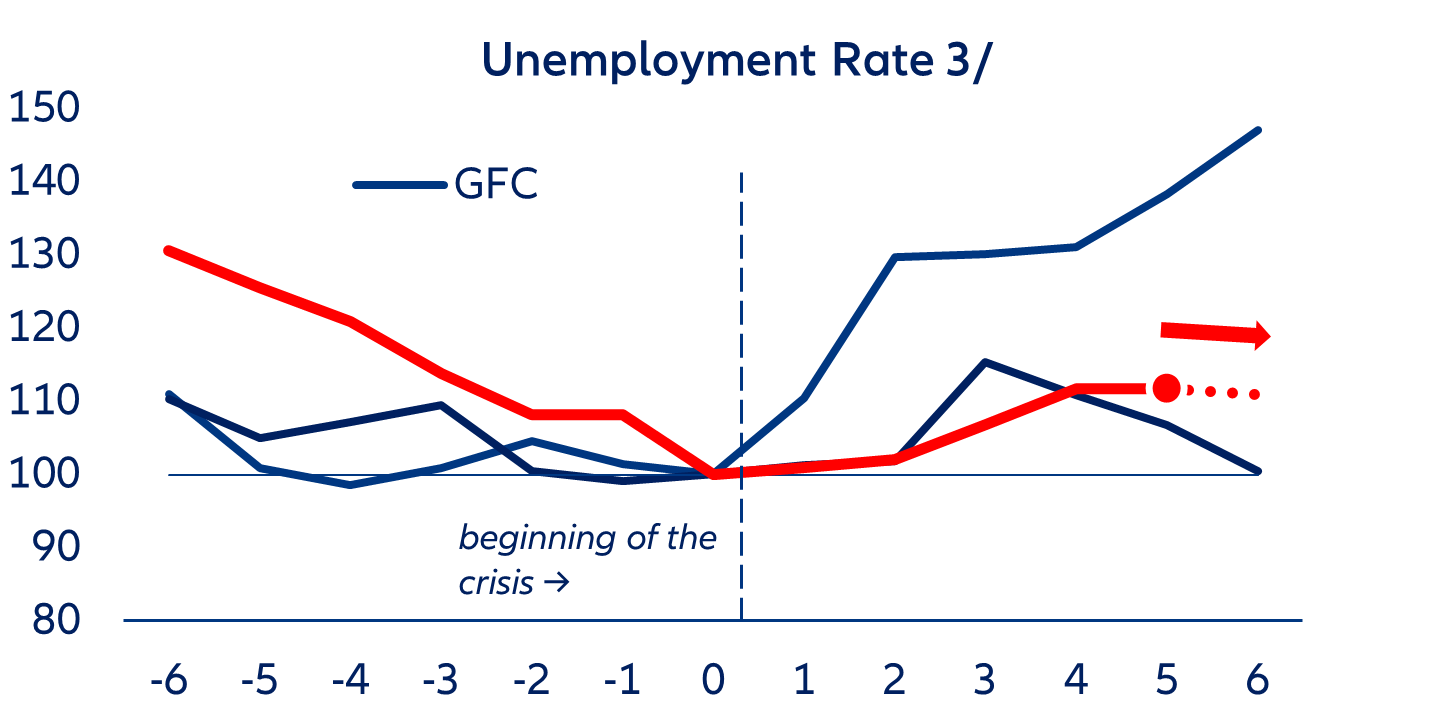

Despite extraordinary crisis support (also compared to other jurisdictions), many heavily indebted firms in the Eurozone will continue to struggle. The Eurozone has slipped back into recession and at the end of the year, the bloc’s economy will be barely larger than it was before the pandemic. Insolvency rates have already started increasing again, but delayed insolvency proceedings and a shallow recession thus far have helped keep corporate defaults low. These suppressed bankruptcies are hiding considerable losses, which could rapidly manifest once the effects of strong policy support have faded, given the buildup of corporate leverage and still weak fundamentals. In fact, many small businesses are still barely afloat and will therefore need to be wound up or restructured. Unless addressed early, worsening corporate profitability could quickly turn into losses – and these liabilities would become real losses for the sovereign.

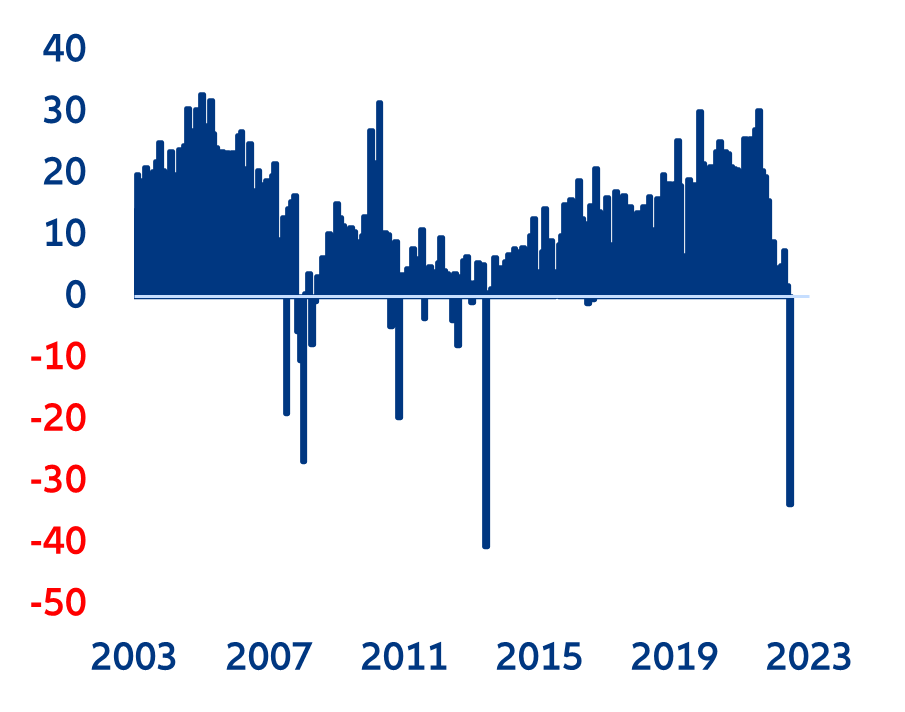

Over the next few years, the Eurozone could become trapped by a combination of weak fundamentals and excessive policy interventions amid rising geopolitical tensions and secular challenges (e.g. climate, demographics and technological change). This would exacerbate vulnerabilities from mispriced risk, while underlying fundamentals continue to worsen. But as the credit cycle turns negative (with money supply having turned negative for the first time ever) and fiscal policies become restrictive, the economy must eventually “snap back” to weak fundamentals. With new lending depressed, economic activity would stall.

In an extreme adverse scenario, the complex system of interlinkages between real activity, banks and sovereigns means that an incipient corporate necrosis would spread rapidly, triggering a fundamental repricing of risk in a new “doom loop” (Figure 17). A trickle of defaults in some critical and well-connected sectors could grow rapidly into a torrent, and the sudden realization of losses would jolt capital markets, precipitating a systemic crisis that reverberates through corporate, financial and sovereign feedback loops.

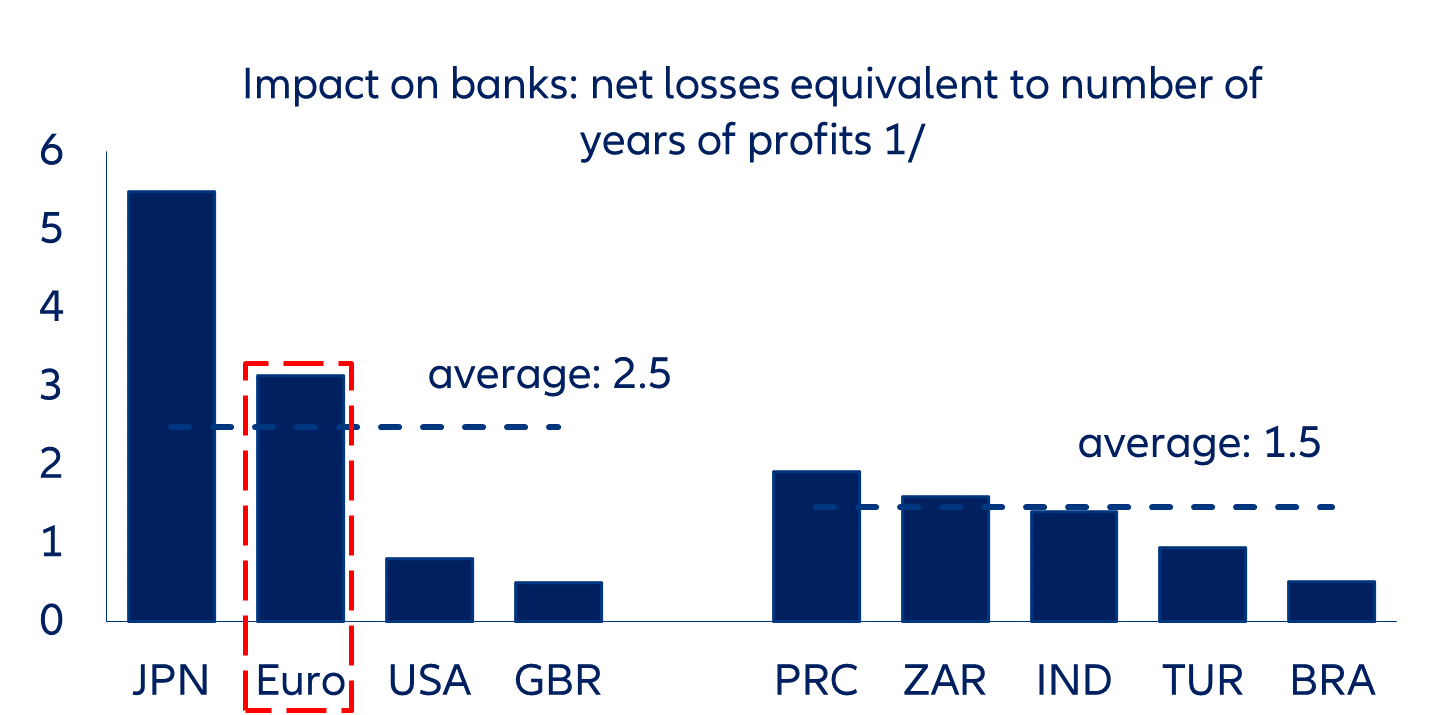

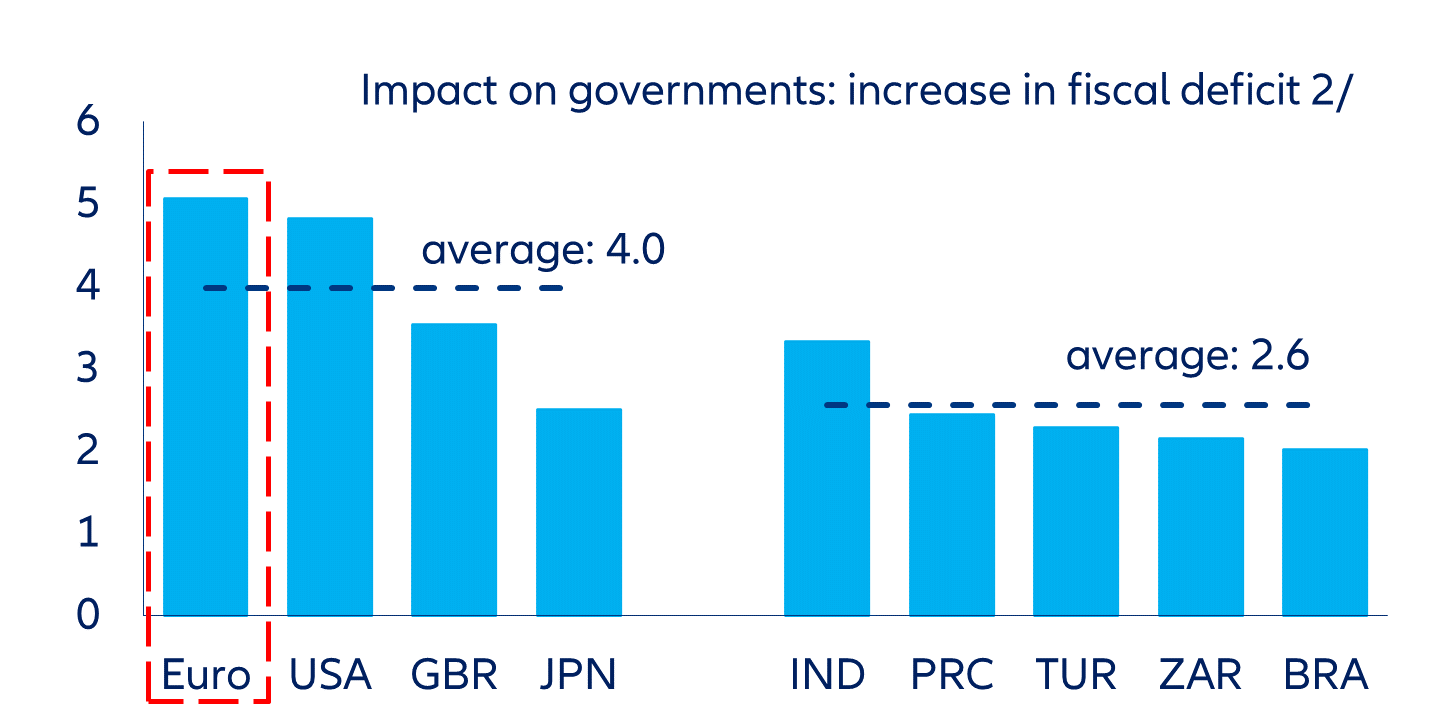

If we conservatively assume default rates seen in previous crises, we can expect a cumulative default rate of 10% over the next two years in this extreme scenario. This would imply a steep increase in insolvencies, based on a current annual default probability of less than 1%. Under these assumptions, losses in the corporate sector would wipe out about three years of bank profits (Figure 18). Banks would respond by cutting back on their riskiest lending to preserve capital – typically to SMEs that need it most. Given sovereign exposures to corporates, the public sector would also bear losses – including up to 5% of GDP on average from direct losses and foregone corporate tax revenues – which would cut deeply into what little policy space is left (Figure 18). In this situation, the Eurozone would find itself in a prolonged recession, but this time with more debt and minimal policy space for yet another fight.

While this scenario remains extreme, it underscores that financial sector policies in the Eurozone need to be become more forward-looking regarding potential corporate sector risks. This is especially the case in some countries where slower insolvencies and lower asset-recovery rates would amplify economic scarring, threatening to undermine the financial system and erode valuable policy space. To reduce the debt overhang ex post, swifter, more efficient and more robust debt-resolution frameworks are needed, including simplified insolvency procedures for SMEs, hybrid restructuring mechanisms and out-of-court workouts.

Pre-emptive policies must include urgently completing the Banking Union. Despite the single supervision and resolution of banks, the Banking Union remains incomplete, with attendant risks of potential fragmentation during times of stress. In recent years, progress to close important gaps, such as the design and implementation of the European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS), has lost momentum and will require a new push to reach consensus and encourage greater cross-border banking. While the European Commission has adopted a proposal to adjust and further strengthen the EU’s existing bank crisis-management and deposit-insurance (CMDI) framework, with a focus on medium-sized and smaller banks, it ignores the role of effective national institutional protection systems and the importance of EDIS (also in resolution) for completing the Banking Union.