- The European Commission’s new Economic Security Strategy could not have come sooner, with its focus on boosting Europe’s competitiveness and deepening the Single Market as essential elements for safeguarding the bloc’s economic security. The pandemic and the energy crises stress-tested the EU’s resolve in forming a strong political consensus. It emerged battle-hardened but severely weakened economically. Now the “European project” finds itself – yet again – at a critical stage of development that requires safeguarding its economic future amid rising geopolitical tensions and domestic pressures.

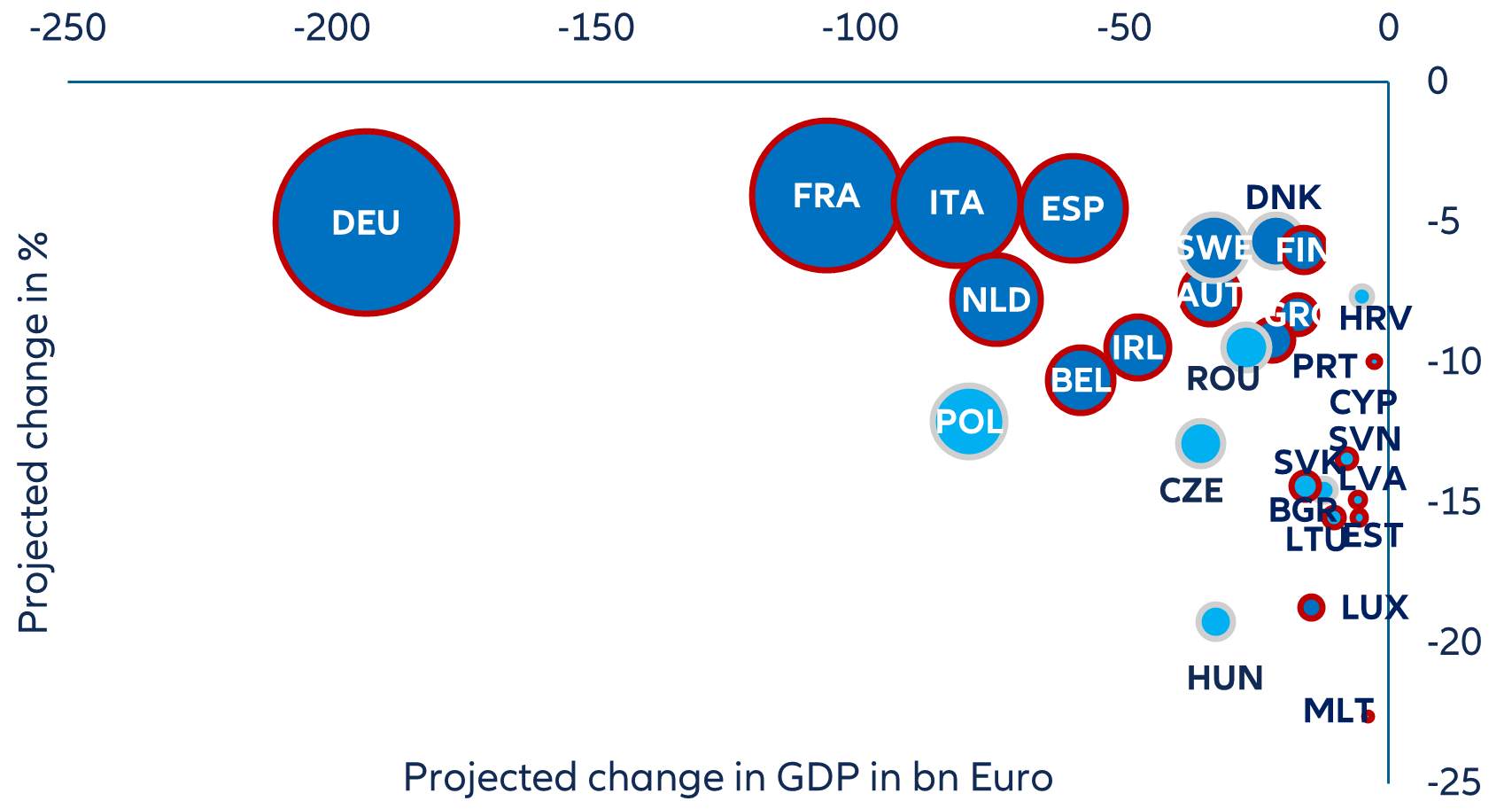

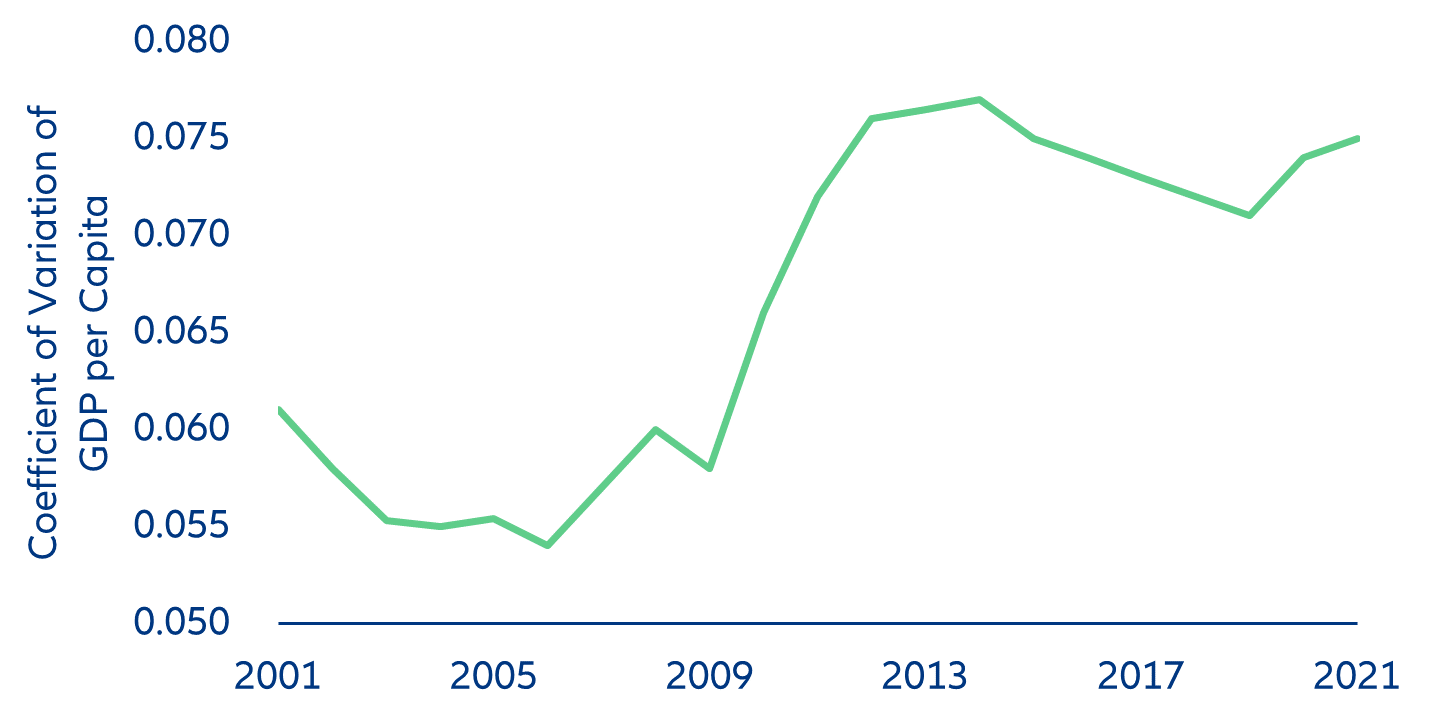

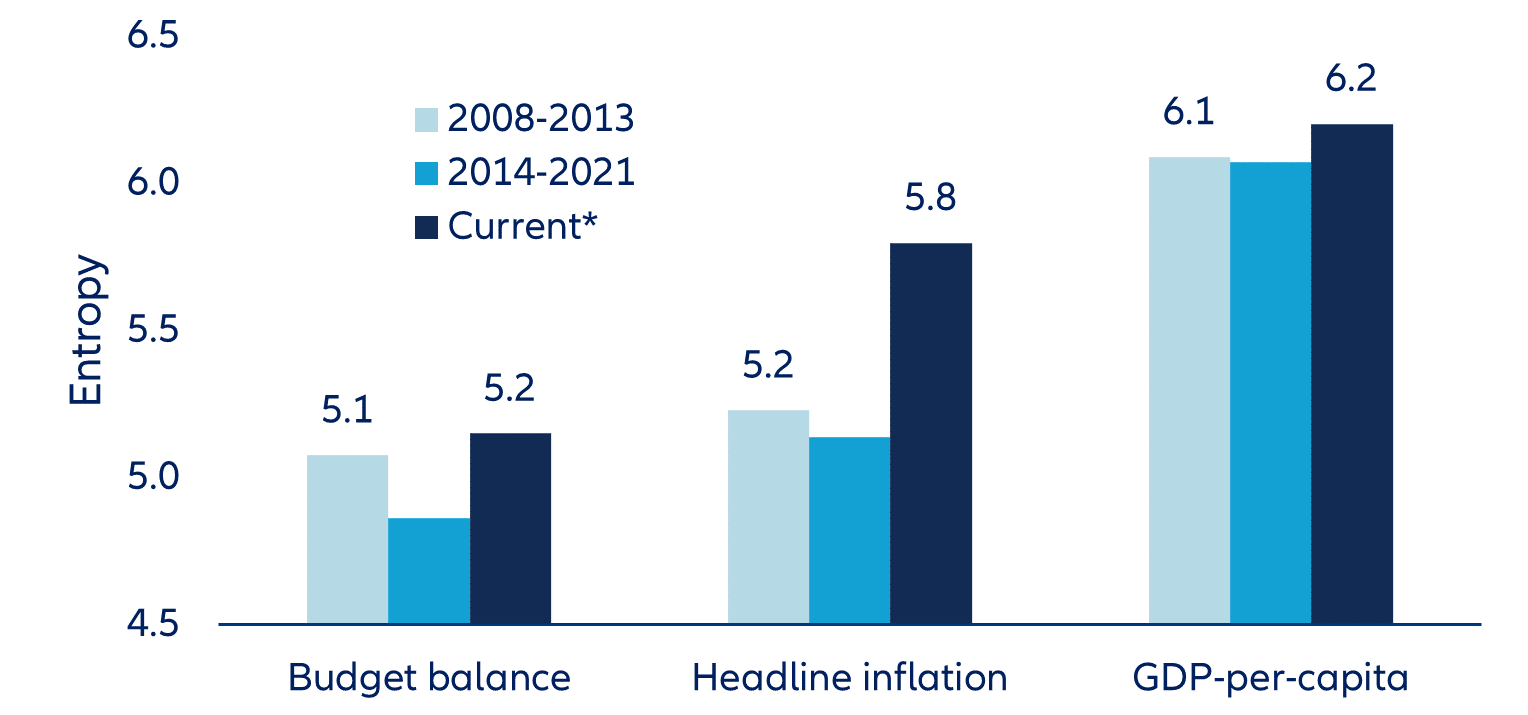

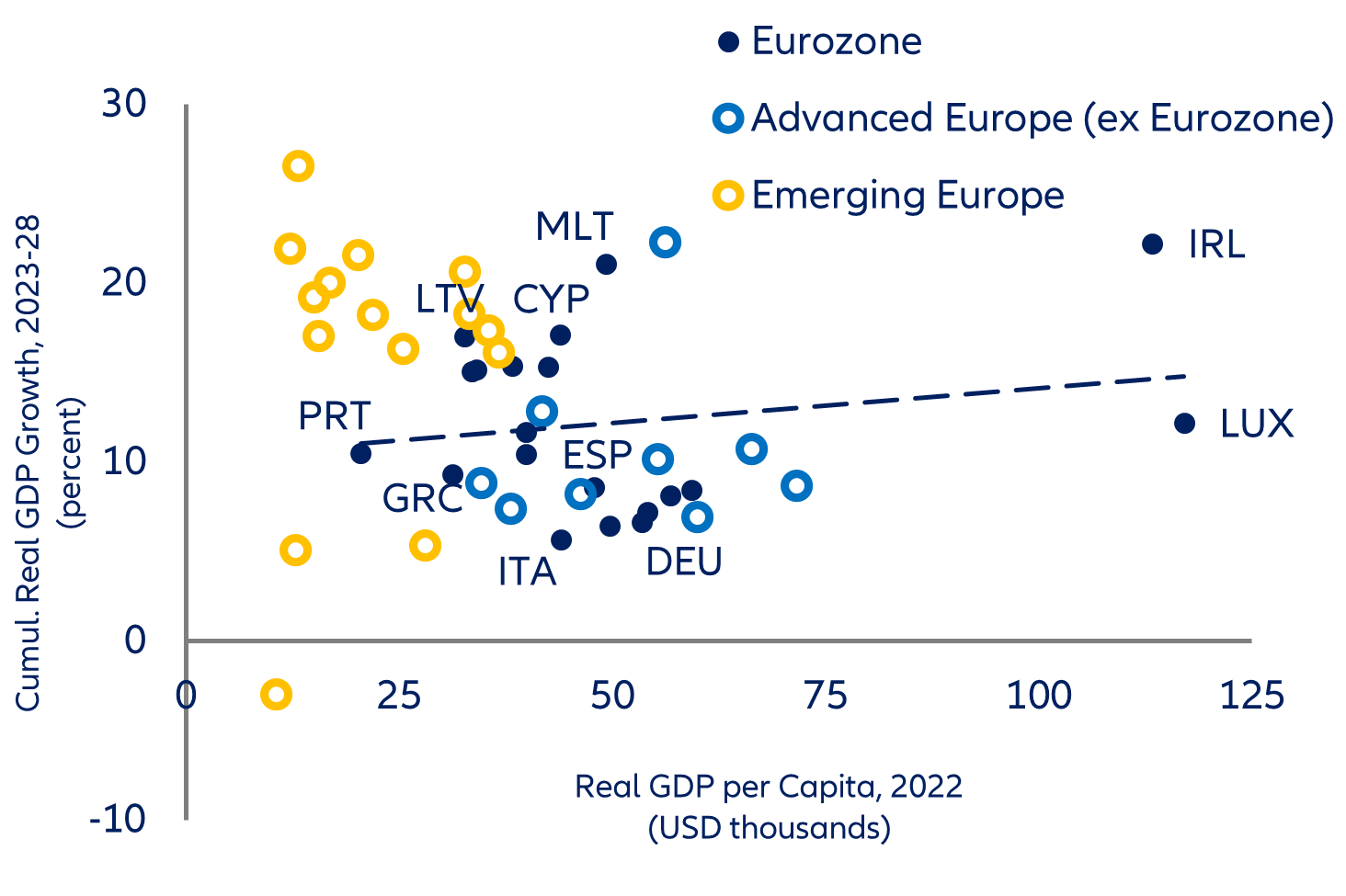

- While the Economic and Monetary Union has helped increase convergence across countries over the last two decades, the momentum has significantly slowed. In fact, regional disparities are on the rise. In addition, the uneven recovery from the crises is set to increase the income gap as projected growth remains broadly the same across most member countries with still large differences in GDP per capita.

- Clearly this trend warrants asking the critical question as to how the Eurozone can achieve meaningful convergence. Deepening the EMU requires greater financial integration and better coordination of fiscal policies. Completing the banking and capital markets unions, as well as reforming fiscal rules, will ensure a deeper and stronger Eurozone.

In focus – Eurozone convergence: two steps forward, one step back

US labor market – soft landing, but not enough for the Fed

The US labor market seems to be rebalancing painlessly. Labor shortages remain acute, with a vacancy-to-unemployed ratio at 1.8, only a touch below the maximum level reached last December (2.0). However, rebalancing is underway. On the demand side, job vacancies were down to around 10mn in April (JOLT survey), which is -16% from the peak in March 2022 (and around 40% of the pre-pandemic level). On the supply side, the labor force participation rate (labor force over the working-age population aged 15 to 70) stood at 68.6% in Q1 2023, only 0.2pp below the 2019 average. Others measures of labor-market tightness such as the quit rate and the job-search rate are also gradually normalizing.

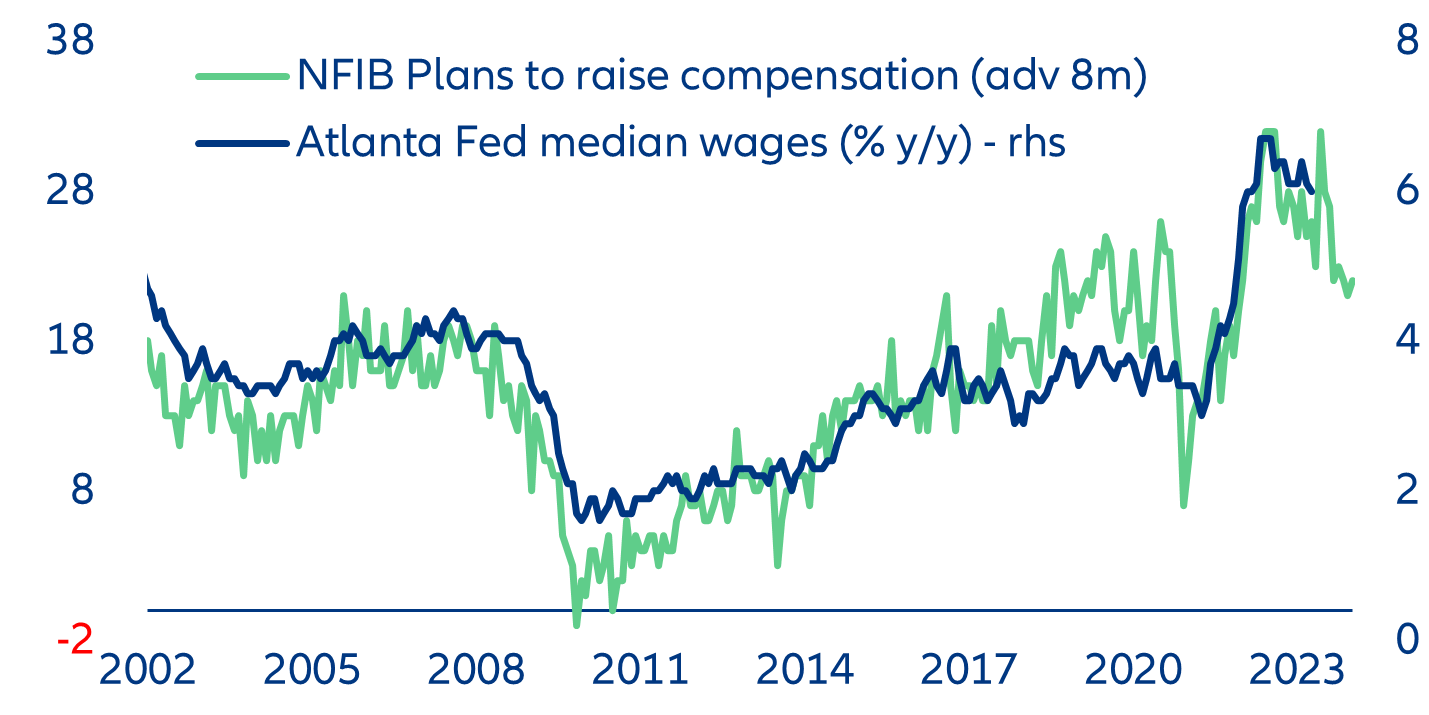

We expect a soft landing of the labor market despite weakening growth as companies accept lowering their margins. The first signs are already visible with still low unemployment, together with normalizing inflation. The vacancy rate is indeed easing without causing much of a pick-up in the unemployment rate. The fall in job openings so far mostly reflects lower hiring (the layoff rate is remains low). On the other hand, we believe that wage growth and inflation will normalize by the first half of next year (see below).

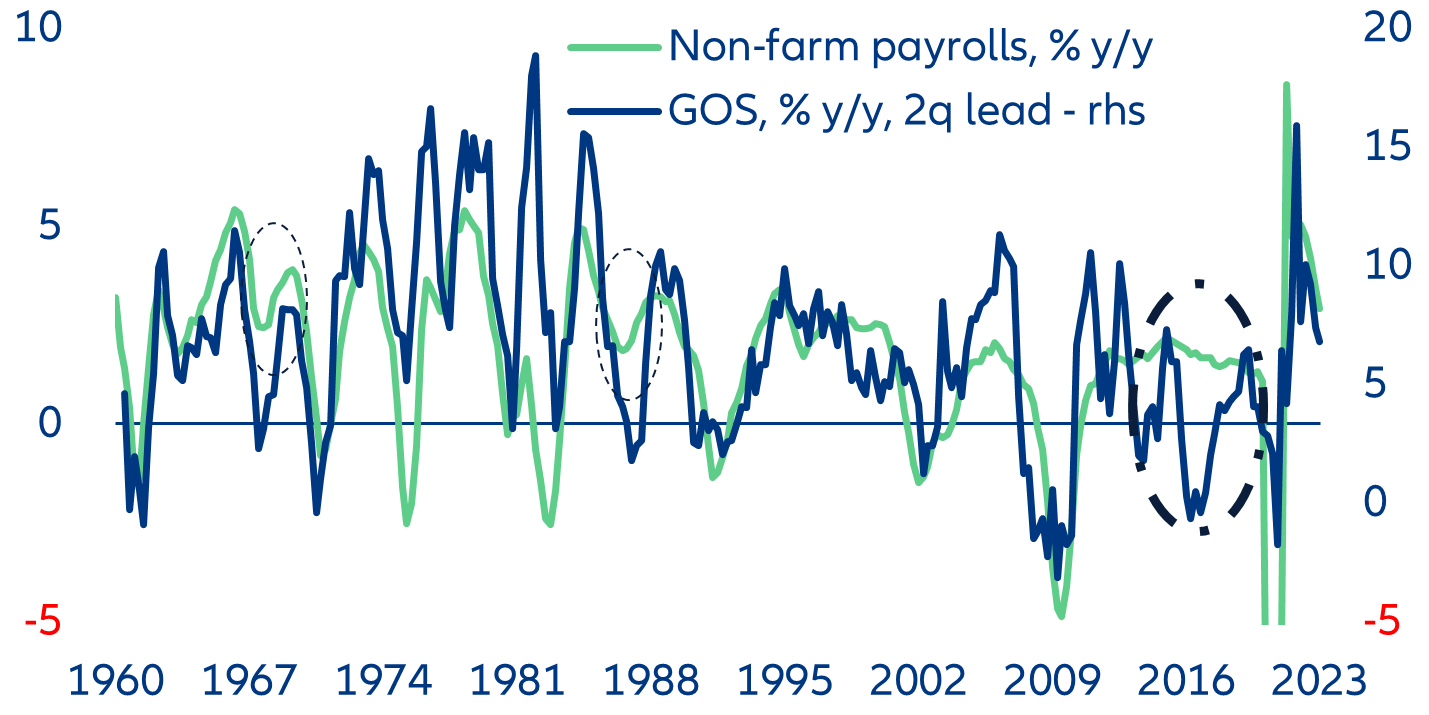

Amid deteriorating demographics and difficulty in hiring after the pandemic, we believe that companies will favor staff-hoarding strategies even as growth slows sharply by the end of the year. Weakening demand induced by rising interest rates is already making a dent on companies’ margins, which have been falling on a q/q sequential basis since Q4 2022. Yet companies continue to hire, an unusual but not unique pattern last seen in the 1960s, during the end of the 1980s and in 2016-17 (Figure 1). Labor costs seem to adjust via lower working hours: Private weekly hours workers per head have dipped to their lower 2011-2019 bound in May. We expect the unemployment rate to peak at 4.2% in Q2 2024, from 3.6% in Q2 2023.

China’s increasing constraints call for more (policy) action

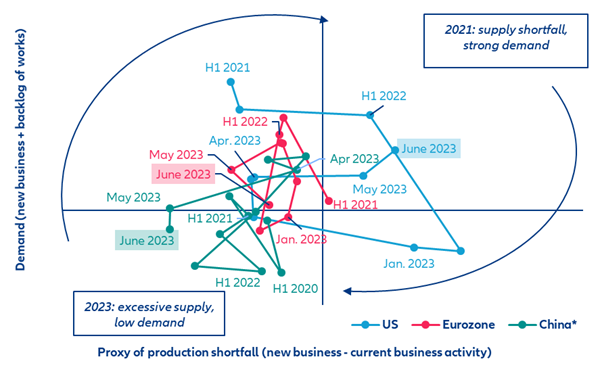

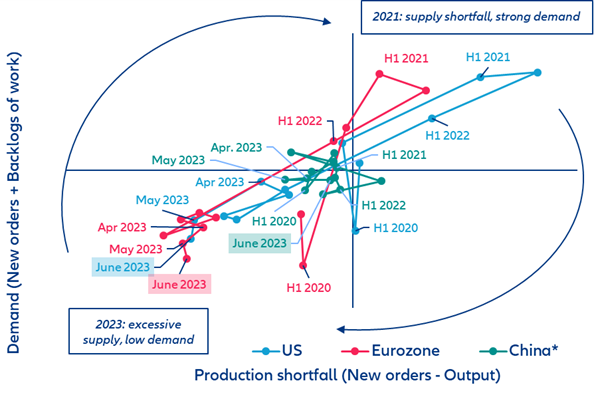

As expected, China’s economic growth continues to lose steam: soft business sentiment data for both manufacturing and services in June support our GDP growth forecast of only +1.3% q/q in Q2, down from +2.2% in Q1. A NBS Manufacturing PMI reading of 49.0 and a decline of the Caixin Manufacturing PMI to 50.5 (down from 50.9 in May) underscore sluggish economic activity in manufacturing. Activity in services is also slowing. The NBS Non-manufacturing PMI declined to 53.2 for June (down from 54.5 in May), and the Caixin Services PMI hit 53.9 (down from 57.1 in May).

Deflationary pressures are intensifying. The input and output price sub-indices suggest that prices kept falling for both construction and services sectors, although at a slower pace compared to May. In the manufacturing sector, amid easing delivery constraints and falling demand, deflationary pressures have strengthened, which shows in the softening of sub-indices for input prices. PPI prices fell by close to -4.6% y/y in May and inflation should decline to less than 1% by end-2023. This warrants at least one more rate cut (-10bps) by Fall this year (to 3.45% for the one-year Loan Prime Rate and 7% for the Reserve Requirement Ratio, which should boost traditional funding and the limit the rise in shadow banking.

The labor market is under pressure, which does not bode well for consumer confidence. In the manufacturing sector, the employment sub-index remained well below the 50 mark. But it is a mixed picture in services: The equivalent sub-index of the Caixin rose slightly to 51.9 in June from 51.5 in May, suggesting an improving labor market in the services sector while it was deteriorating in the NBS survey. In construction, the NBS survey showed a deteriorating outlook for employment. That does not bode well for consumer confidence. Youth unemployment is over 20%, on the back of skills mismatches, and some migrant workers have taken lower-paid service jobs this year instead of working in export factories, given the weakness of external demand, notably in advanced economies.

In this context, more policy support is needed. In response to the slowdown, policymakers are trying to implement further counter-cyclical measures, including recently approved support for home-related consumption. The recent State Council meeting also deliberated on further measures to boost consumption and increase spending on urban renovation projects. Policymakers are likely to avoid implementing broad-based stimulus (such as large cash handouts to households), focusing rather on targeted fiscal measures going forward, including the increase in local government special-bond quotas. The share of annual quotas stood at 61.7%, much below 2022 levels.

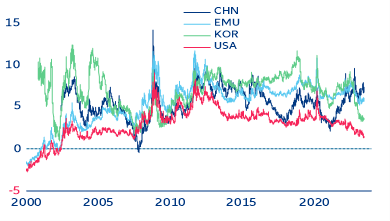

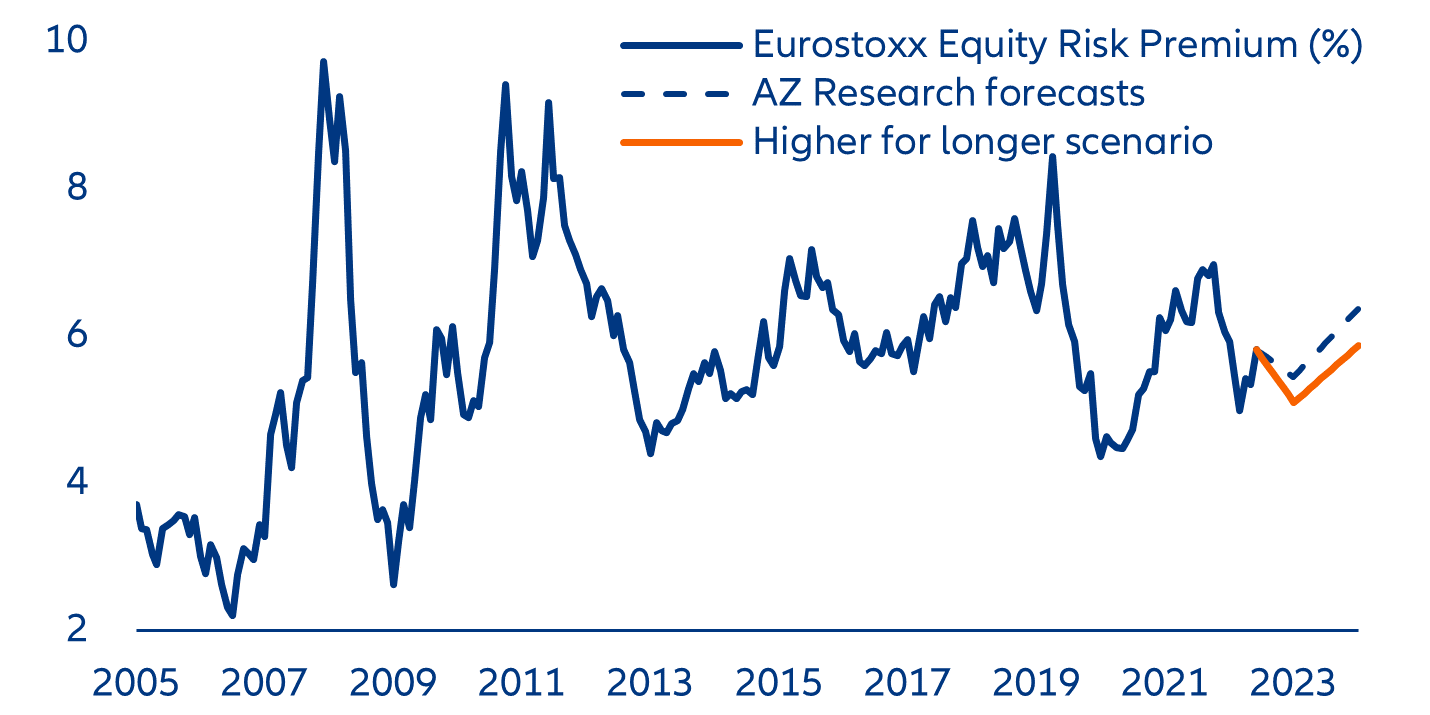

China’s re-opening has not boosted capital markets. Even though opportunities remain compelling given the large size of China’s economy and still strong growth prospects, valuations are far lower relative to other major markets in advanced economies. The equity risk premium is about four times as high as in the US (Figure 5). While low correlation with major markets should be attractive during a time of limited diversification possibilities, capital account restrictions make foreign investment less efficient.

What if the ECB goes “higher for longer”?

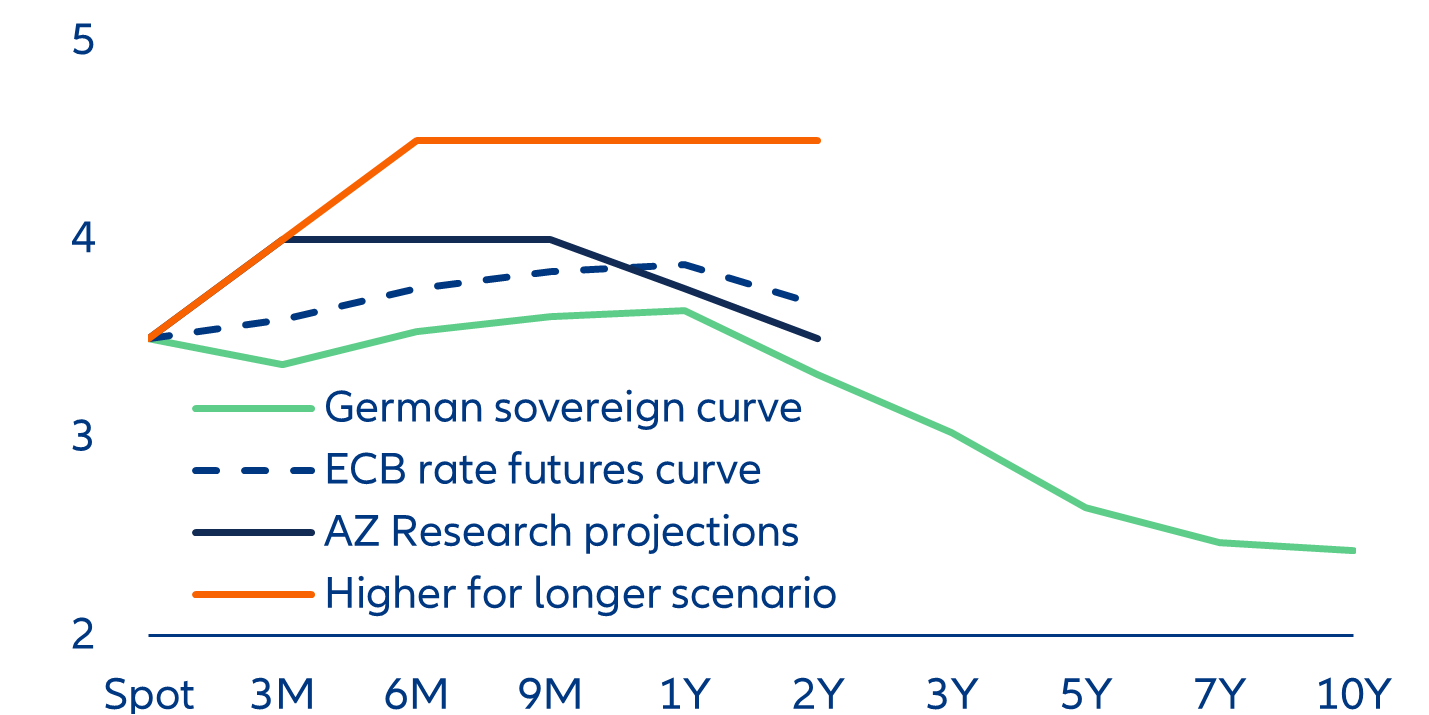

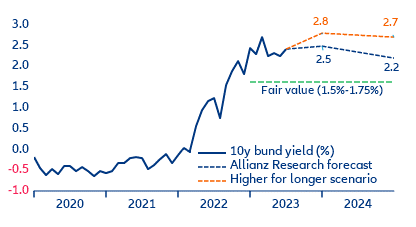

Stronger-than-expected core inflation has lowered the bar for the ECB to keep interest rates higher for longer. While headline inflation for June came in line with expectations at 5.4% y/y (down from 6.1% y/y in May), core inflation increased to 5.4%Y (up from 5.3% y/y in May). Services inflation has risen again to 5.4% y/y (from 5.0% y/y in May) as expected, and with a notable base effect from the EUR9 ticket in Germany. Goods inflation decreased to 5.5% y/y (from 5.8% y/y) but less than expected. On a monthly basis, price changes are now much weaker than they were in early 2023 and disinflationary forces (outside services) are gaining momentum as monetary supply keeps declining. Even before the recent inflation data releases, we had already revised up our terminal expectation for the ECB to 4.0%,[1] assuming that it will continue to hike even after its July meeting by another 25bps in September. However, what is more important is the increasingly hawkish tone from the ECB, which became apparent at last week’s Central Bank Forum in Sintra. The divergence between the forecasts of the national central banks (June and December) and the forecast of the ECB (March and September) on the stickiness of inflation has raised the degree of data dependency in the ECB’s policy-rate path. It seems unlikely that the ECB will forecast meeting its medium-term price stability target of 2% before the end of 2025, which would could postpone potential rate cuts from June 2024 (our current forecast) to 2025.

In focus – Eurozone convergence: two steps forward, one step back

The “European project” finds itself – yet again – at a critical stage of development that requires safeguarding its economic future amid rising geopolitical tensions and domestic pressures. The pandemic and the energy crises stress-tested the EU’s resolve in forming a strong political consensus. It emerged battle-hardened but severely weakened economically. At its heart, the Eurozone has slipped back into recession amid still far-too-high inflation. At the end of this year, the bloc’s economy will be barely larger than it was before the pandemic – equivalent to four lost years. However, strong growth and productivity are a necessary, if not sufficient, condition for Europe’s economic self-determination. Rising geopolitical tensions between the US and China (and more broadly the “collective West” vs. the “collective East”) amplify security concerns in national politics and economic policy – and challenge Europe’s mercantilist growth model underpinned by a strong commitment to globalization. At the same time, cracks in the system have become more apparent and require more focus on the domestic agenda, including rising inequality (e.g. inefficient labor markets and lagging regions), political ambiguity (e.g. a sense of loss of control and accountability) and pressing secular challenges (e.g. climate, demographics and technology).

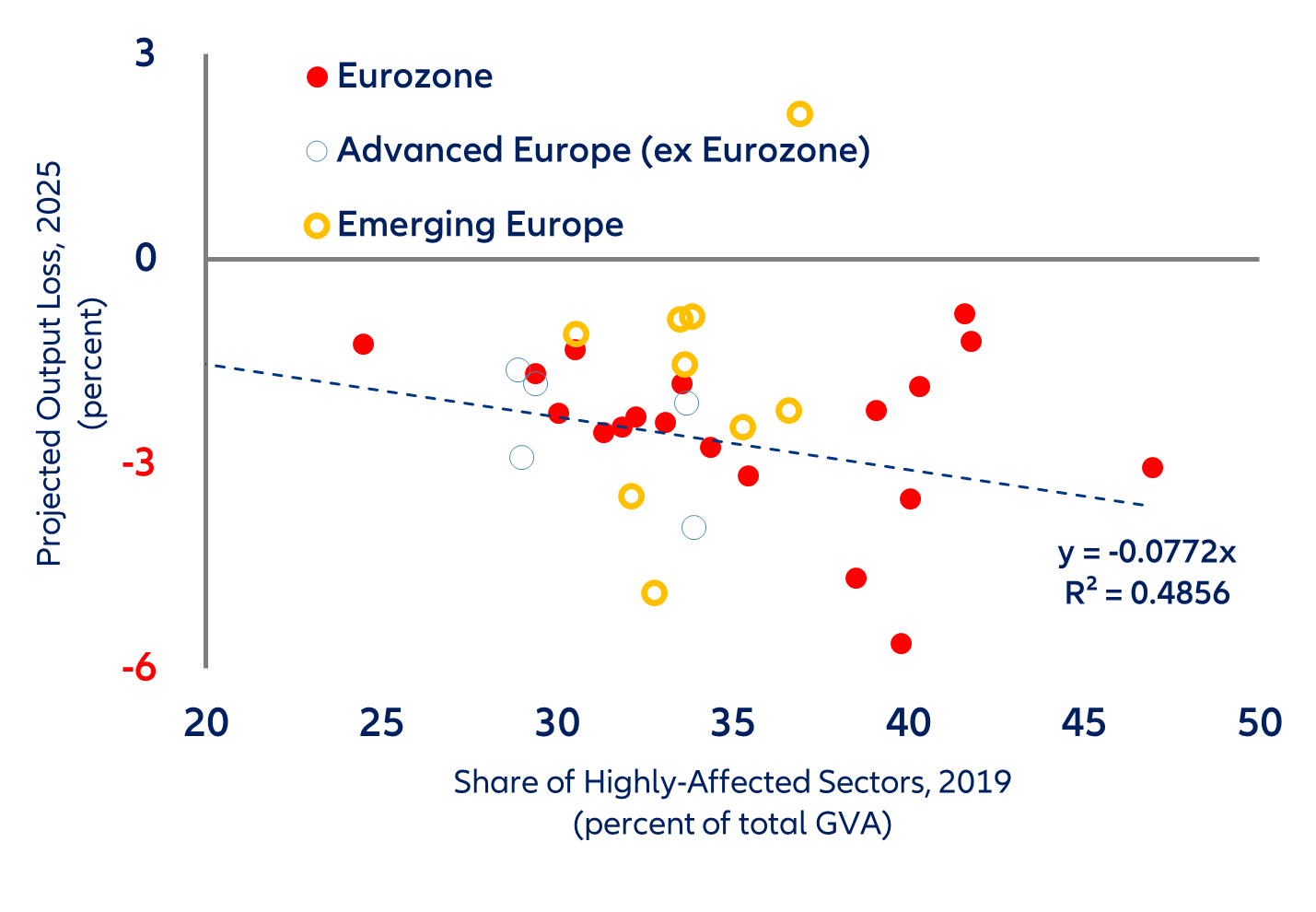

In this context, the European Commission’s new Economic Security Strategy could not have come sooner, with its focus on boosting Europe’s competitiveness and deepening the Single Market as a priority for safeguarding economic security. But it is also complicated by an uneven recovery from the recent crises. Some sectors and firms have yet to fully recover (or might slowly disappear), while others are set to expand more rapidly, including those benefitting from less dependence on fickle trading partners, deeper technological changes and the transition towards a greener economy. This means that there will be some economic scarring, albeit significantly less than in the period following the global financial crisis, which will vary considerably across member states. Restoring trend growth will be challenging, especially in regions of Europe that have been falling behind.

Figure 12: Europe – GDP-per-capita and growth (percent, US thousand dollars)

Figure 13: Europe – share of highly-affected sectors vs. output loss (percent, percent of total GVA) 1/

Clearly, this trend warrants asking the critical question as to how the Eurozone can achieve meaningful convergence. Deepening the EMU requires greater financial integration and better coordination of fiscal policies.

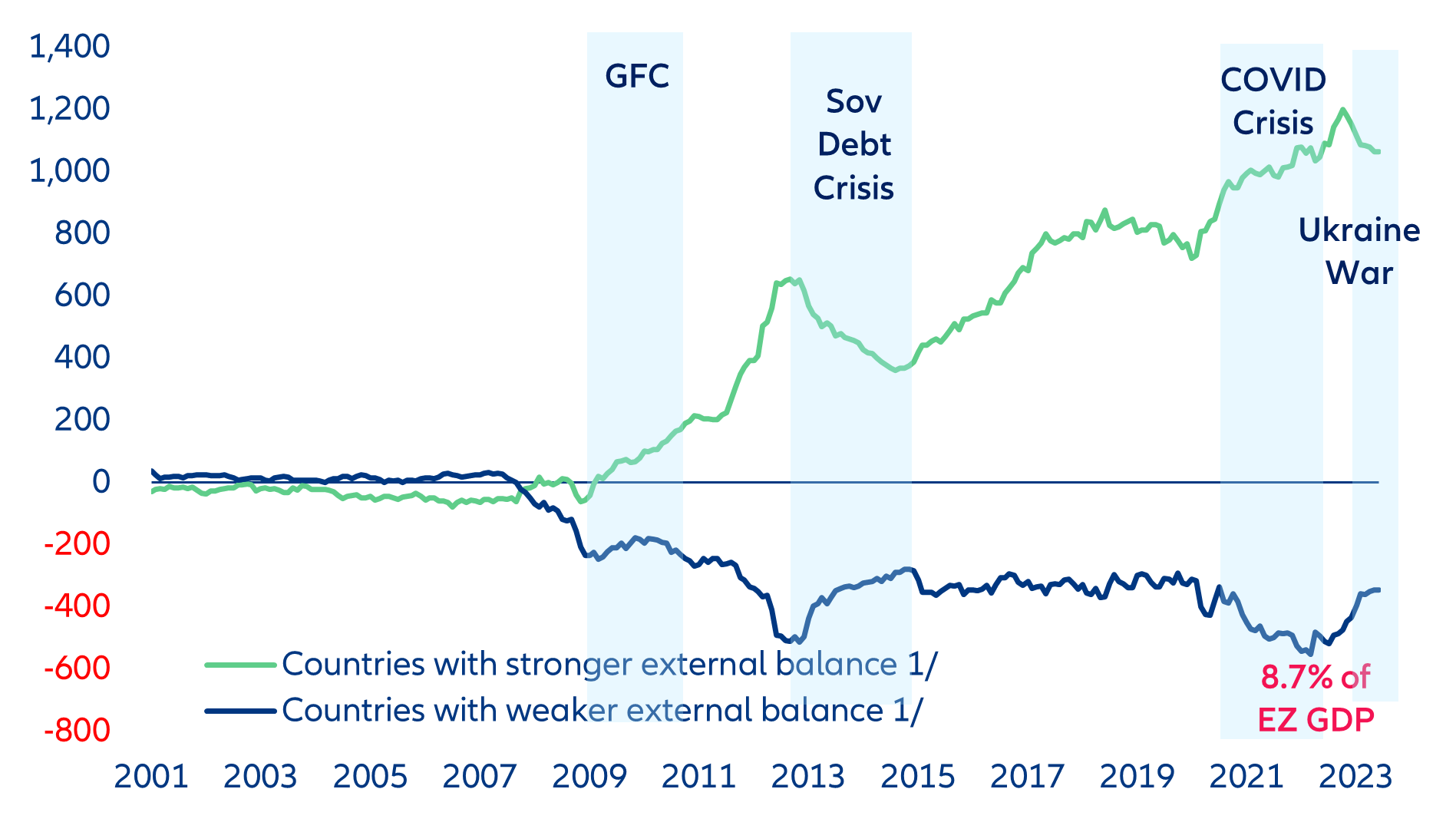

- Banking Union: The pandemic and the energy crises have not precipitated a banking crisis, in part because banks were much better capitalized and less risky than before the GFC. Despite the single supervision and resolution of banks, the Banking Union remains incomplete, with attendant risks of potential fragmentation during times of stress. In recent years, progress to close important gaps, such as the design and implementation of the European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS), has lost momentum and will require a new push to reach consensus and encourage greater cross-border banking. While the European Commission has adopted a proposal to adjust and further strengthen the EU’s existing bank crisis-management and deposit-insurance (CMDI) framework, with a focus on medium-sized and smaller banks, it ignores the role of effective national institutional protection systems and the importance of EDIS (also in resolution) for completing the Banking Union.

- Capital Markets Union (CMU): Increasing cross-border private risk-sharing and reducing firms’ reliance on bank financing in Europe requires better integrated capital markets. Advancing the capital markets union is critical to EU resilience. Capital markets should also play a key role in financing the transition to a greener, more digital economy. The new 2020 CMU action plan identified several steps needed to “reboot” the EU’s push for greater capital market integration. Fast implementation of these recommendations would make access to market-based finance easier and lessen firms’ reliance on bank borrowing.

- Fiscal framework: Credible EU fiscal rules are essential for an effective monetary union. Earlier this year, the European Commission proposed the most ambitious overhaul of the EU fiscal framework in more than two decades. The focus on a simplified expenditure-growth rule as a single operating target (and removing the structural-balance rule) offers an opportunity for vulnerable Eurozone economies to gradually reduce their budget deficits while making the necessary investments to boost potential growth. Retaining a focus on growth-enhancing spending would be critical for the country to stabilize debt once current cyclical pressures from the energy crisis abate and give way to structural challenges from the green transition. Recognizing that countries have emerged from the crises with elevated debt levels, preserving a deficit rule anchored to nominal growth with a more flexible adjustment period for fiscal consolidation seems to be a reasonable solution. But not excluding public investment from the limits of the fiscal rules should raise concerns; Europe’s central fiscal capacity for more public investment remains too small.