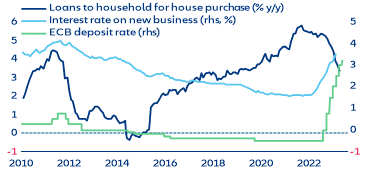

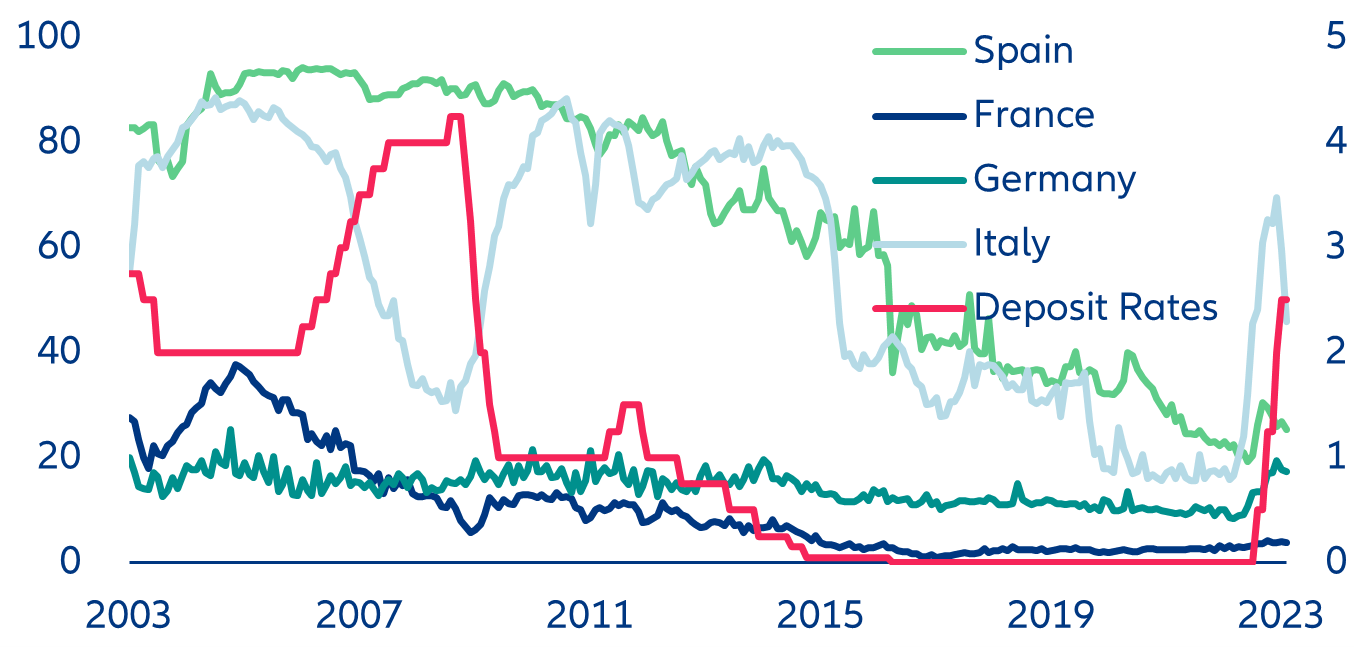

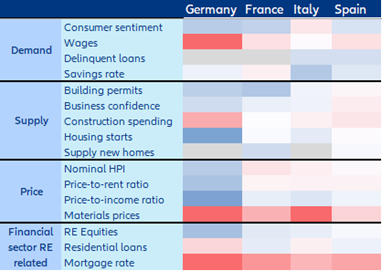

- The rapid tightening of financing conditions increasingly weighs on the housing market. Credit demand has weakened, and consumer confidence is low. There has also been a shift to variable-rate mortgages, suggesting that borrowers expect an improvement in financing conditions and do not want to lock in high rates. However, this also reflects continued interest-rate uncertainty as fixed-rate borrowing is becoming much more expensive.

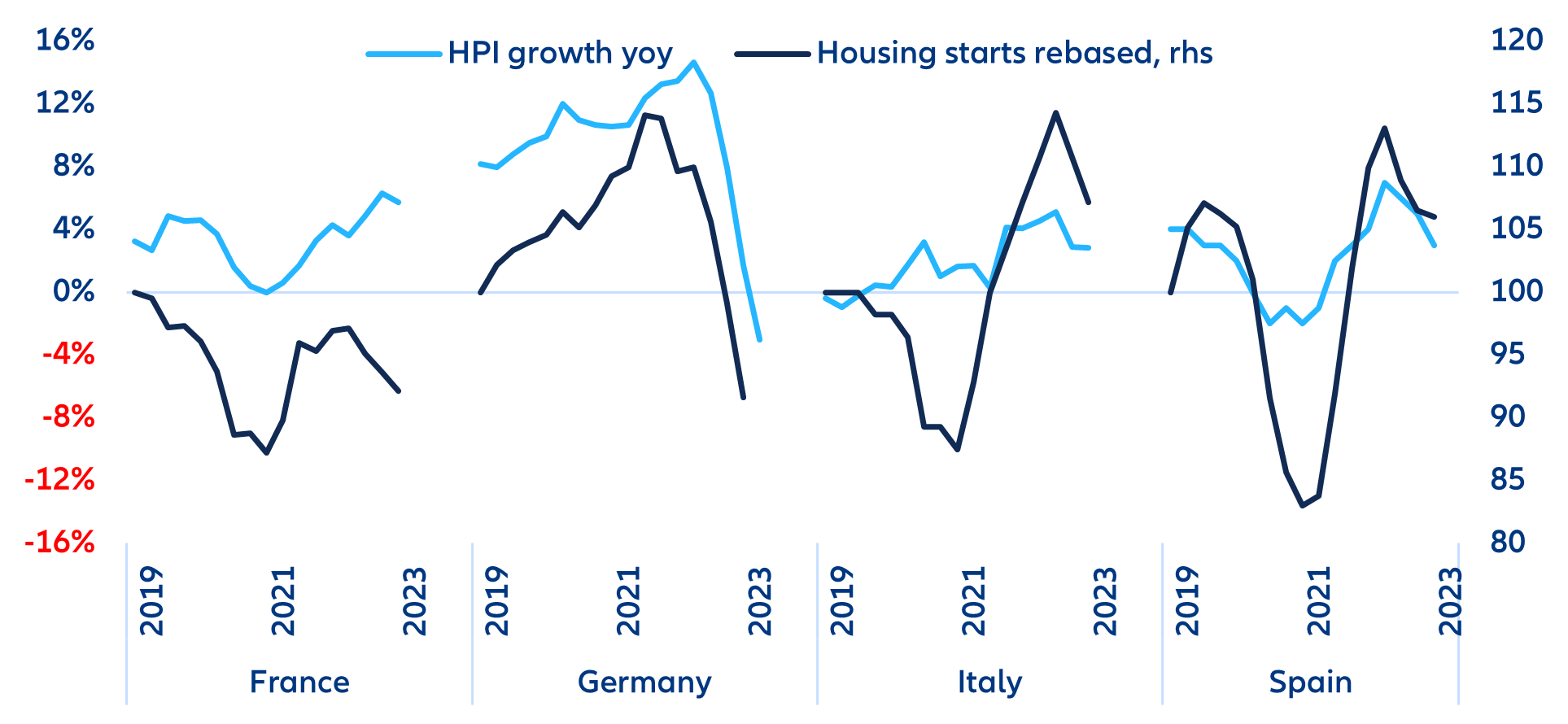

- Supply constraints may cushion the adjustment on house prices, further exacerbating deteriorated home affordability. The total cost of purchasing a home has increased due to higher interest rates despite a decline in house prices. Together with the overheating in house prices in 2020-21 (or since 2014 for countries like Germany), debt burdens are becoming unsustainable, especially for the younger generation, which has mostly been priced out of the market.

- The ineffectiveness of public policies in tackling the structural challenges of home affordability contrast with the swift response to the temporary Covid-19 shock. As supply of new homes is scarce, well-functioning social housing and more balanced regulation of the rental market should become policy priorities.

What to watch:

- Raising the roof – bipartisan deal on debt ceiling likely to focus on spending restraints amid growing fiscal deficits

- Italy’s bold vision – energy plan and fiscal challenges

- Headed towards a “Minsky Moment” – what if the US banking crisis is not over?

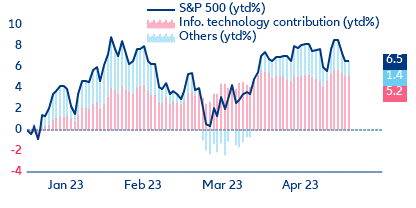

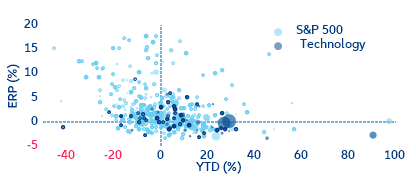

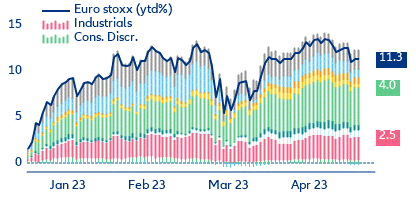

- Equity market sector rotation – tech rising like a phoenix from the ashes

In Focus

European housing – home (un)sweet home?

Raising the roof – bipartisan deal on debt ceiling likely to focus on spending restraints amid growing fiscal deficits

We still expect Congress Republicans and the White House to reach an agreement (even a temporary one), but an accident cannot be ruled out due to a tight legislative agenda. Neither the GOP nor the White House want to be accused of manufacturing a default. At the very least, the two sides are likely to agree on suspending the debt ceiling over the near term if a comprehensive deal cannot be reached before 1 June. The new deadline could then be pushed towards late July or end September – the end of the fiscal year – when a deal on spending levels for FY2024 will be necessary. However, there is a risk that the federal government could struggle to make payments on its debt by 1 June if cash resources are depleted much faster than anticipated in the next two weeks because of the tight legislative agenda. The House is scheduled to be in recess this week and again starting 26 May, while the Senate recesses the week of 22 May, returning 29 May. The chances of a misstep are therefore far from negligible. That is why the market is now assuming a much higher probability of a default this time around, with the one-year Credit Default Swap spread (the cost of insuring against a default) skyrocketing.

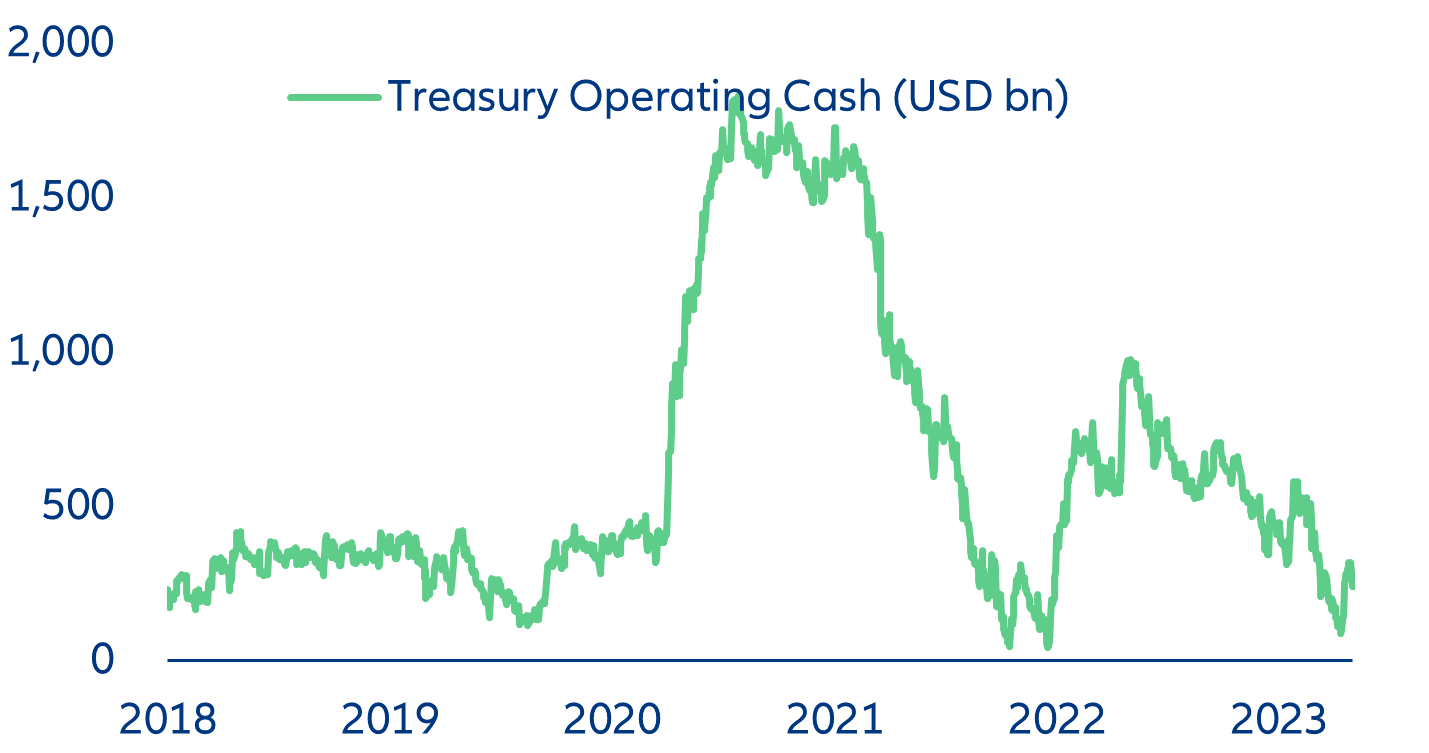

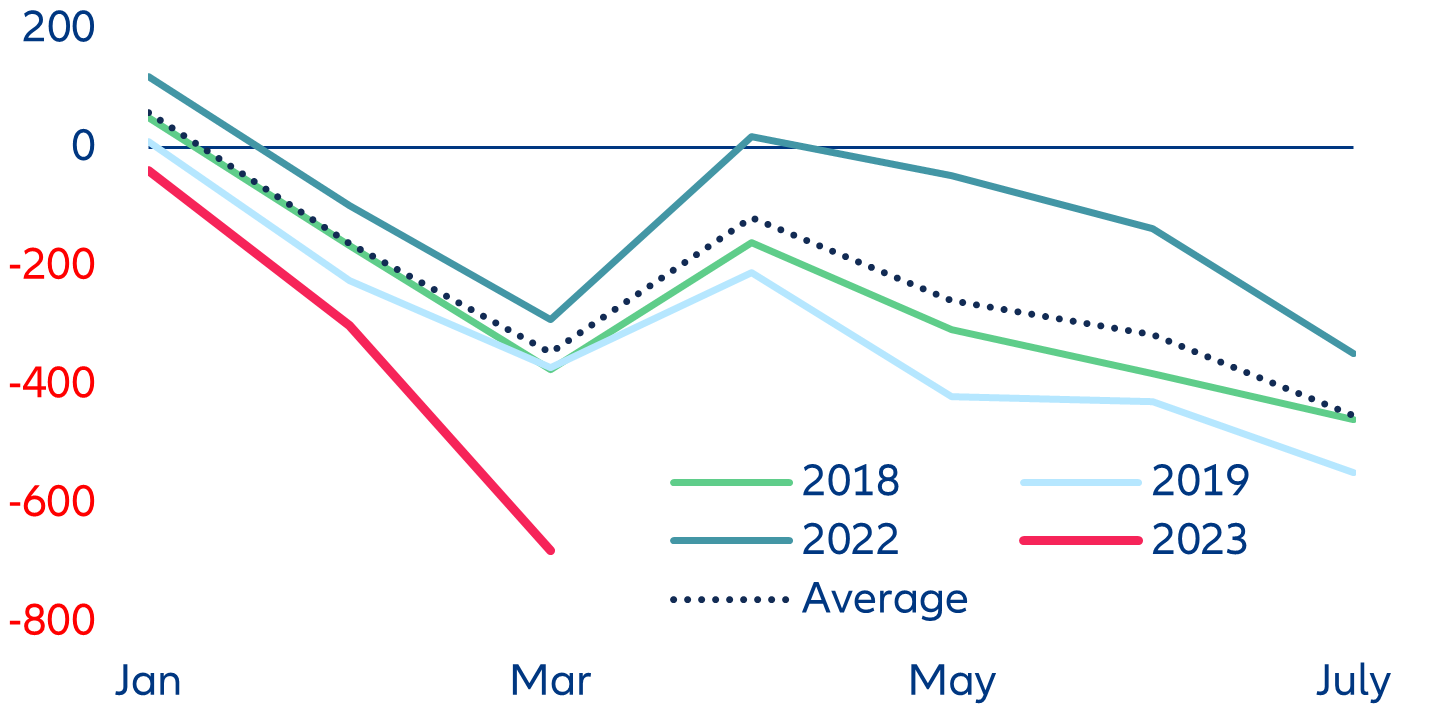

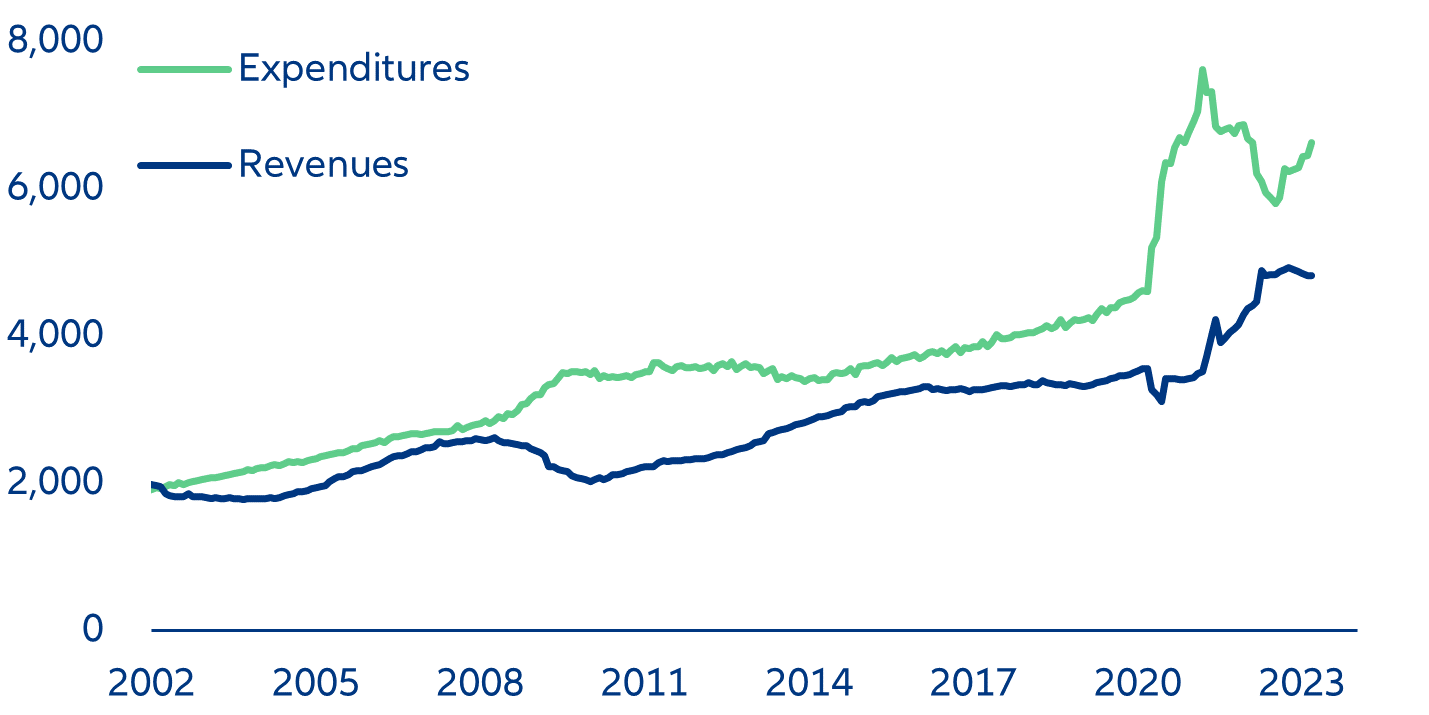

The core underlying issue of the debt-ceiling drama is how soaring spending has been blowing up the federal government deficit since the end of last year. In March, the Treasury’s cumulative shortfall (receipts minus spending) over the first three months of 2023 reached a whopping -USD679bn (Figure 2), much worse than in preceding years (excluding the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021).

Italy – energy plan and fiscal challenges

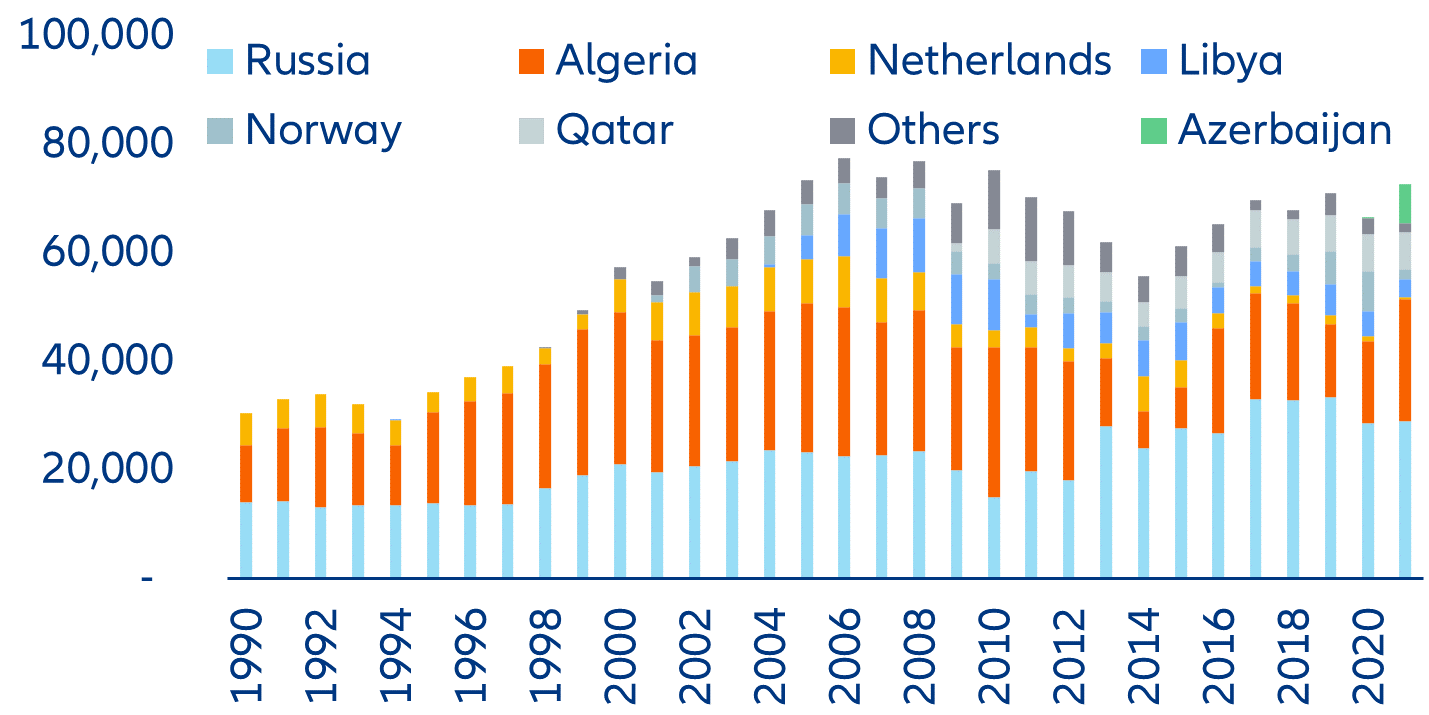

Building on the successful energy-diversification talks, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni recently launched an energy-cooperation agreement with Africa, dubbed the “Mattei Plan”, to use Italy’s storage capabilities to distribute gas from North Africa and the Mediterranean to the rest of Europe. More details on turning Italy into a central energy hub for Europe will be revealed in October; however, the first concerns have already come up. First, geopolitical risks could unsettle the plan as Northern African countries are often subject to political turmoil, which could complicate negotiations. Moreover, a “European” solution would be better to address the energy-supply challenge rather than multiple national solutions that tend to benefit bigger and more industrialized countries. However, Italian energy companies such as ENI – the national energy company – have a good track record in investing in African countries, and have recently signed important gas collaboration agreements.

Given that the Next Generation EU funds will also contribute to improve the country’s energy strategy, recent “spending fears” are justified. More than 30% of the resources allocated to Italy will support its green transition by investing in energy efficiency in residential and public buildings (EUR15.3bn); sustainable mobility (EUR34bn) and the development of renewable energies and the circular economy and improvement in waste and water management (EUR11.2bn). In the first two years of the program, activation of public investment was moderate, so a strong catch-up in spending capacity is needed over the horizon to make up for the lags. All eyes remain on Italy’s administrative ability to manage an unprecedented amount of resources.

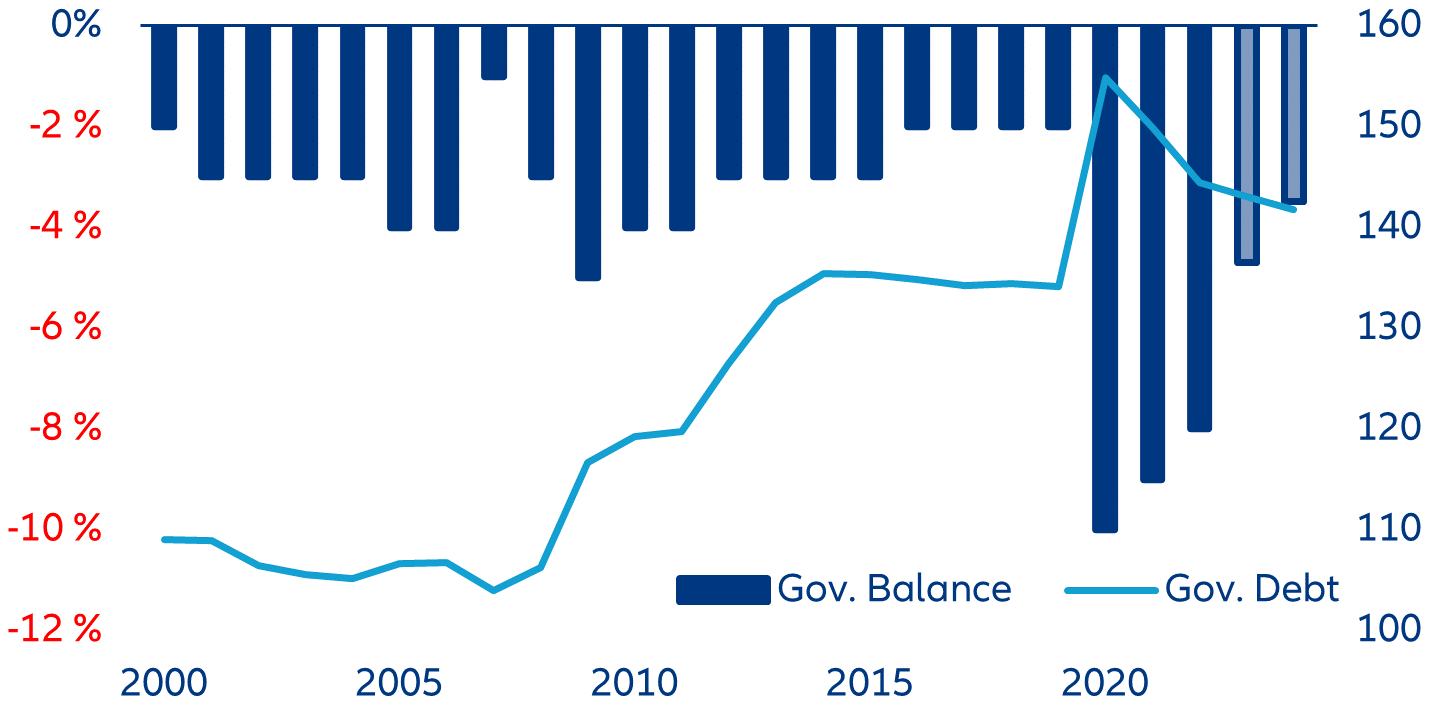

Another important test for the government will be the medium-term fiscal dynamics in a context of higher interest rates, normalizing inflation and slowing economic growth (Figure 5). Italian government debt-to-GDP decreased by more than 5pps in 2022 to 144.4% (down from the 2020 peak at 155%) thanks to high inflation. But the government deficit has widened, given the new Eurostat accounting method for tax credits (“superbonus”). This scheme, in place since 2020, provides a 110% transferable tax credit to households for housing renovation works (of up to EUR200k) to improve the environmental efficiency of the housing stock. As a result, the fiscal deficit reached 8% in 2022, down from 9.0% in 2021 (-1.8% revision). But as the new methodology should have produced mainly backward revisions, we still expect a consolidation trend for the government balance in the coming years (our forecasts see the deficit at 4.7% in 2023 and 3.5% in 2024). Indeed, the new government is more fiscally prudent than previously expected, and some expensive and not-very-targeted measures (i.e. superbonus and universal income) have been tweaked in recent months.

However, we expect the ECB’s monetary tightening to impact Italian fiscal trends. Even with a higher overall debt level, sovereign interest payments declined as a share of GDP until 2021, but this trend reverted in 2022. In fact, rapidly rising interest rates have significantly increased the Italian government’s debt-servicing costs and raised concerns about debt sustainability. We estimate the public debt burden to reduce only temporarily in 2023 (to 3.7% of GDP, given the price-slowdown impact on inflation-linked bonds) from 4.0% in 2022, but to increase again in 2024-2025 to around 4.2% of GDP. Despite the Italian debt-management agency having secured increasingly longer maturities (weighted average maturity around 7.6 years), which helps reduces rollover risks, debt sustainability will remain in the spotlight, especially after 2026.

Higher borrowing costs will put more pressure on Italy’s government budget and could raise fragmentation risk. Scaled-up public sector support since the onset of the pandemic and throughout the energy crisis has widened the budget deficit and delayed much-needed fiscal consolidation. Moreover, we expect fiscal adjustment to happen only gradually, given the current context, making it more difficult to reduce elevated government debt levels. In Italy, this could also increase fragmentation risk, causing a widening of the sovereign spread (so far contained). However, our estimates suggest that this risk remains rather small, also thanks to the effective signalling effect of the ECB’s transmission protection instrument (TPI).

Headed towards a “Minsky Moment” – what if the US banking crisis is not over?

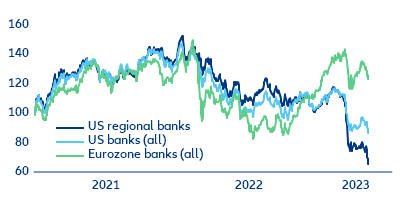

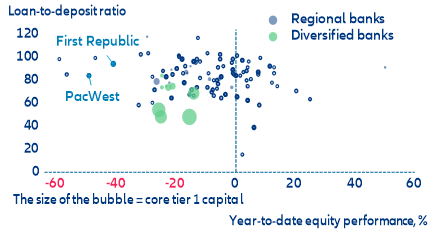

Figure 7: US banks – equity performance vs. liquidity (loan-to-deposit ratio)

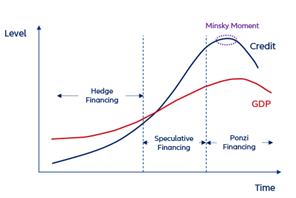

While spillover risks to the broader global financial system have remained limited, the chances of a “Minsky Moment” have increased (Figure 8). This term “Minsky Moment” describes a sudden collapse of asset values following a period of unsustainable growth, often leading to a financial crisis. The term was coined by economist Hyman Minsky (1919-96), who argued that periods of economic stability and prosperity often lead to increased risk-taking by investors and financial institutions, which increases asset-liability mismatches, leverage and interconnectedness, and thus system-wide vulnerability to changes in asset prices. Minsky's theory is based on the idea that the stability of financial systems can lead to complacency as investors and institutions become increasingly confident in their ability to generate profits. This confidence leads to increased borrowing and leverage as investors take on more and more risk in order to maximize their returns. However, as the risks of these investments increase, so does the likelihood of a sudden collapse. This can happen when investors begin to lose confidence in the underlying assets, leading to a rapid sell-off and a steep decline in asset values.

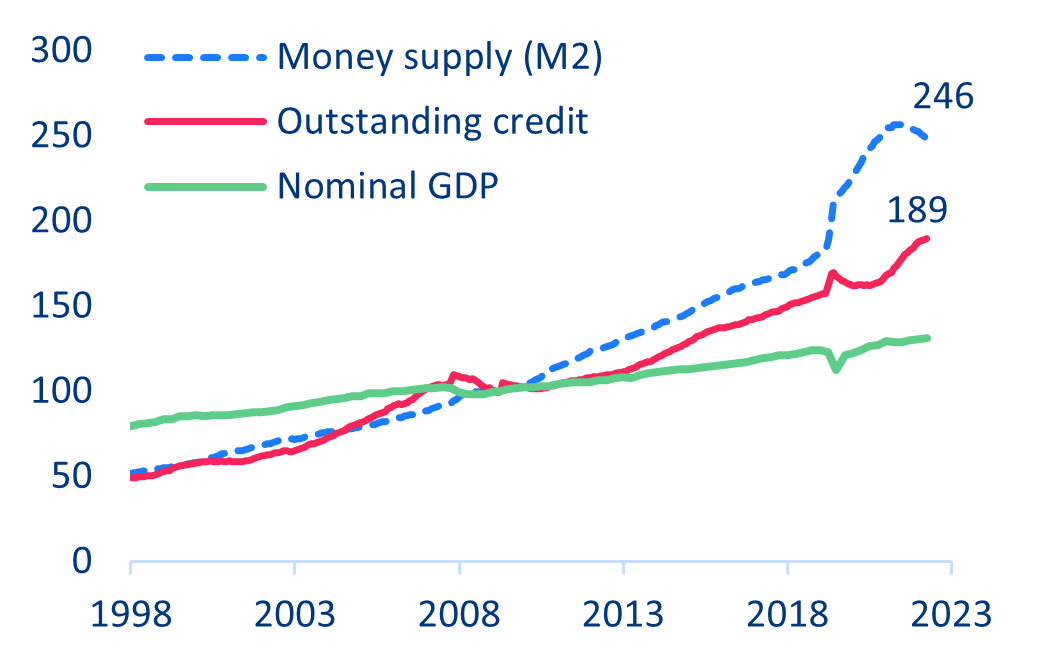

Will we see a systemic risk-triggered re-run of the 2008 crisis? After more than a decade of explosive money supply outstripping nominal growth, the highly financialized US economy has clearly entered a “Ponzi financing” regime, which typically unwinds in a “Minsky Moment”. Households and companies need to keep borrowing more to financing a rising debt burden without a realistic prospect of full repayment. This, in turn, can trigger a credit crunch and a wave of defaults and bankruptcies, leading to a broader financial crisis. While a comparison to the US subprime crisis and its systemic implications may be tempting, there are important differences – the valuation of “combustive material” (CRE) has already corrected significantly (though there is still downside risk), and when banks cut back lending, it tends to hit (riskier) small business lending first – this is nothing extraordinary. However, after a long period of excessive credit growth that increased system-wide leverage, policymakers need to act swiftly to shore up confidence in the banking sector to mitigate spillover risks from quantitative tightening and strengthen backstops to the financial safety net. This needs to be followed by a period of stabilization, with a focus on establishing debt sustainability, probably at the expense of higher growth.

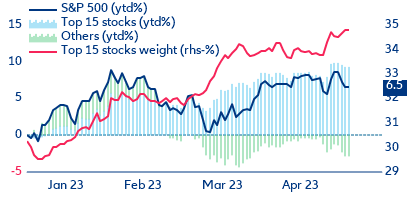

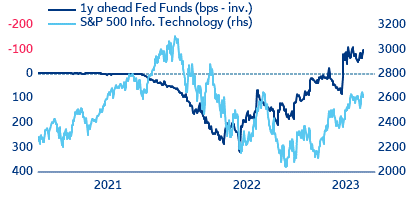

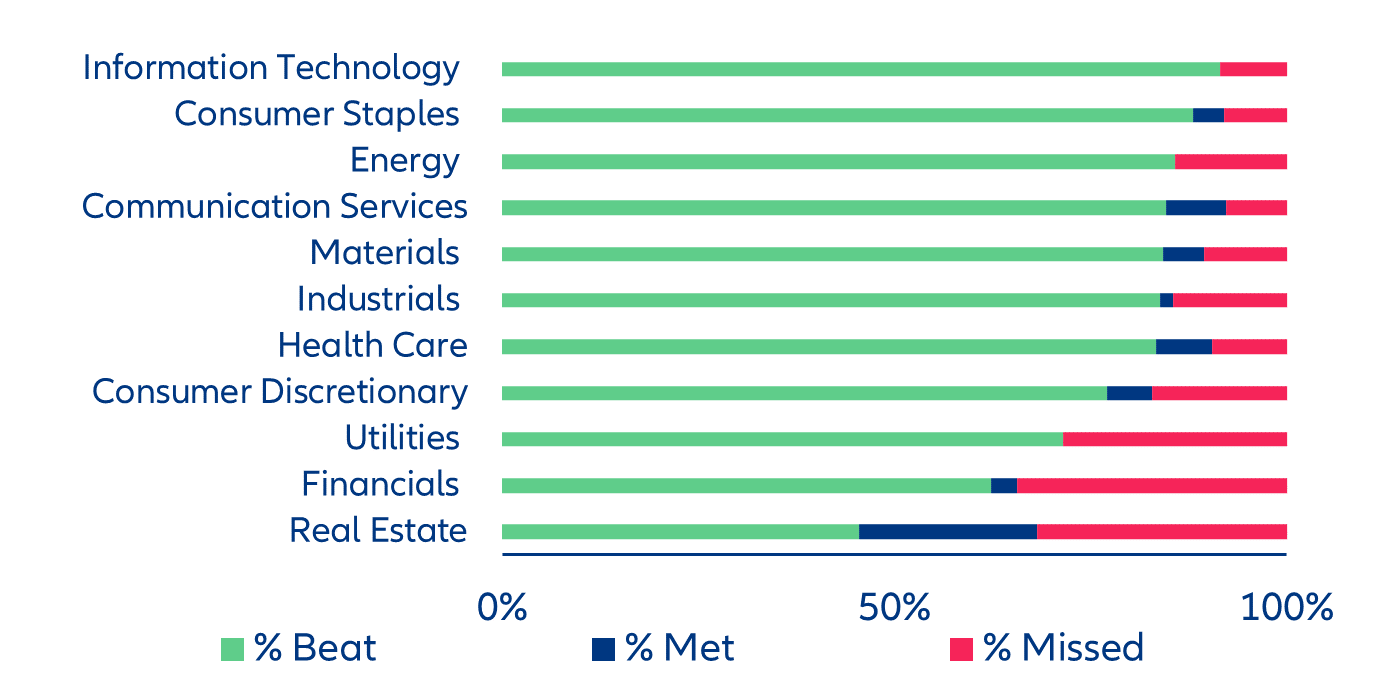

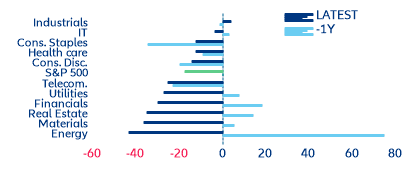

Equity markets – Tech rising like a phoenix from the ashes

Eurozone housing market – home (un)sweet home?

Sources: Refinitiv Datastream, Allianz Research

Sources: ECB, Refinitiv Datastream, Allianz Research

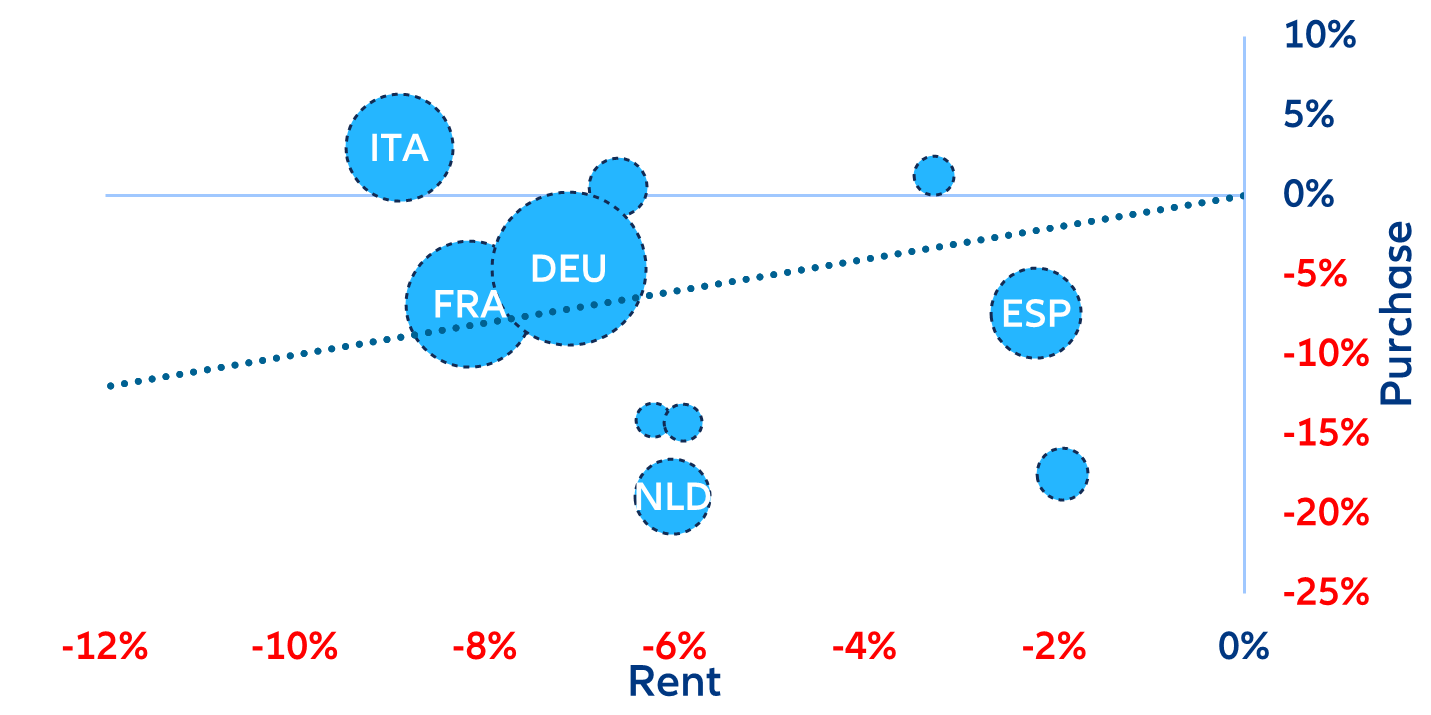

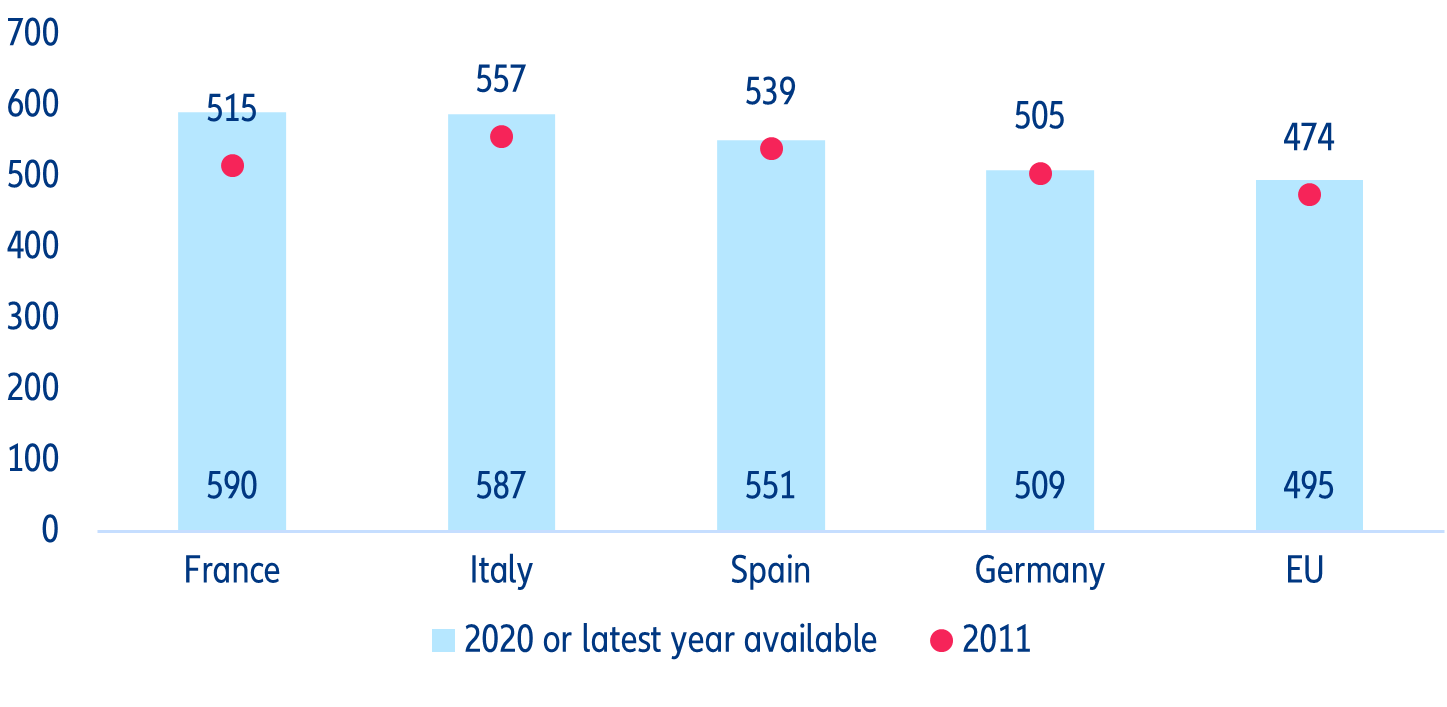

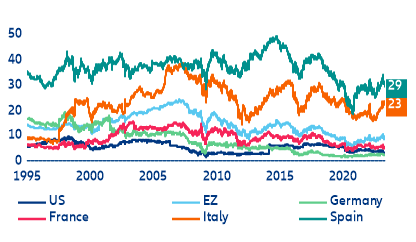

France and Germany’s housing markets are most at risk of (further) price adjustments. We forecast real house price corrections of up to 5% until mid-2024, which would amount to a cumulative correction of 15% compared to end-2021. In France, household demand for new residential mortgages has fallen to historical lows since the second half of 2022. Italy and Spain could muddle through with stagnant property prices. In Italy, the number of potential buyers in the real estate market already decreased over the past year and the average time to sell a house and the average discount on prices have increased after hitting a 10-year low in early 2022. Overall, the shortage of housing is a common feature in all countries, which will counterbalance the downward price pressures and help avoid a crash. In this context, there are increasing calls for more government measures in affordable housing.

More social housing could be the solution to help first-time home buyers that are increasingly priced out of the housing market. The de-coupling between house prices and wages has worsened with the inflation in essential goods that followed the war in Ukraine and the monetary policy U-turn. Households now face budget constraints on multiple fronts, and those that have not already embarked on purchasing a home are not likely to be able to do so in the coming two years. In terms of rent affordability, things are not better, especially in Italy, Germany and France.