- Last Sunday, UBS agreed to buy domestic competitor Credit Suisse in a government-brokered all-share deal for USD3.25bn – the largest bank merger since the global financial crisis. The combined entity will have a balance sheet of USD1.7trn, making it one of the top 10 global banks (and comparable in size to Santander (Spain), Wells Fargo (US) or Barclays (UK)).

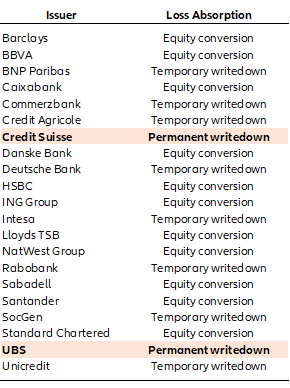

- The complete write-down of Credit Suisse’s USD17.3bn worth of additional Tier 1 (AT1) capital is unusual but legal. Contrary to the conventional bail-in hierarchy of banks’ capital structure, shareholders (which normally rank junior) still received some stock in UBS (albeit at a premium). However, the permanent write-down of such hybrid capital instruments is specific to the two large Swiss banks; all other large European banks have issued AT1 instruments that make the write-down temporary (or covert into equity), which will limit potential spillover effects to the hybrid capital market.

- European banks seem well-shielded but funding and capital costs will probably increase, leading to a market repricing and readjustment. The health of the European banking sector has significantly improved over the last decade, mitigating potential spillover effects of Credit Suisse’s rescue.

- Financial stability concerns will influence but not condition the policy rate path forward. Banking-sector tremors have already tightened global financing conditions but will not do so fast enough for the Federal Reserve and the ECB to abandon their restrictive stance. Thus, central banks’ first response to financial-market stress has been to provide ample liquidity. The preferred option seems to be waiting for inflation to slowly decrease on the back of the lagged effects of monetary policy, without causing dislocations in capital markets.

What to watch:

In Focus

Swiss shotgun wedding: what’s next?

US Federal Reserve – one more rate hike to go

The FOMC pressed ahead with a 25bps rate hike despite the banking turmoil. In line with our expectations, the FOMC hiked interest rates to signal its undeterred commitment to bring inflation down. Chairman Powell acknowledged that liquidity injections (the Fed lent around USD300bn to banks last week) were indeed increasing the size of the Fed’s balance sheet, but emphasized that they would not push up inflation. Liquidity injections are temporary lending intended to meet banks’ liquidity needs and restore confidence, with no effect on economic activity and inflation. On the other hand, interest-rate hikes and quantitative tightening (i.e. reducing the size of the Fed’s bond portfolio) are tools tailored to tame inflation.

However, Powell dismissed concerns about the soundness of the US banking system, arguing that SVB was ‘an outlier’. While calling for a thorough review of current banking supervision and regulation policies, and for the implementation of more stringent ones, he emphasized that the Fed was prepared to use all tools at its disposal to keep the banking system safe and sound, and to protect depositors ‘if there is threat’. Powell nonetheless refused to answer the question of whether the Fed would bail out some banks in case of a systemic crisis.

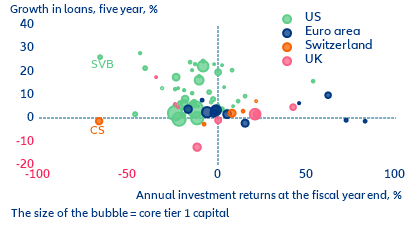

We are less sanguine than Chairman Powell about the health of the US banking system because of the fragility of regional banks. Declines in regional bank asset values significantly increase their exposure to uninsured-depositor runs. According to simulations by a SSRN study[1], SVB was far from being the worst capitalized and having the largest unrecognized losses among US banks. Admittedly, SVB stood out in having a disproportional share of uninsured funding. However, according to the SSRN study, if only half of uninsured depositors decided to withdraw their funds, almost 190 banks would be a potential risk of impairment to insured depositors.

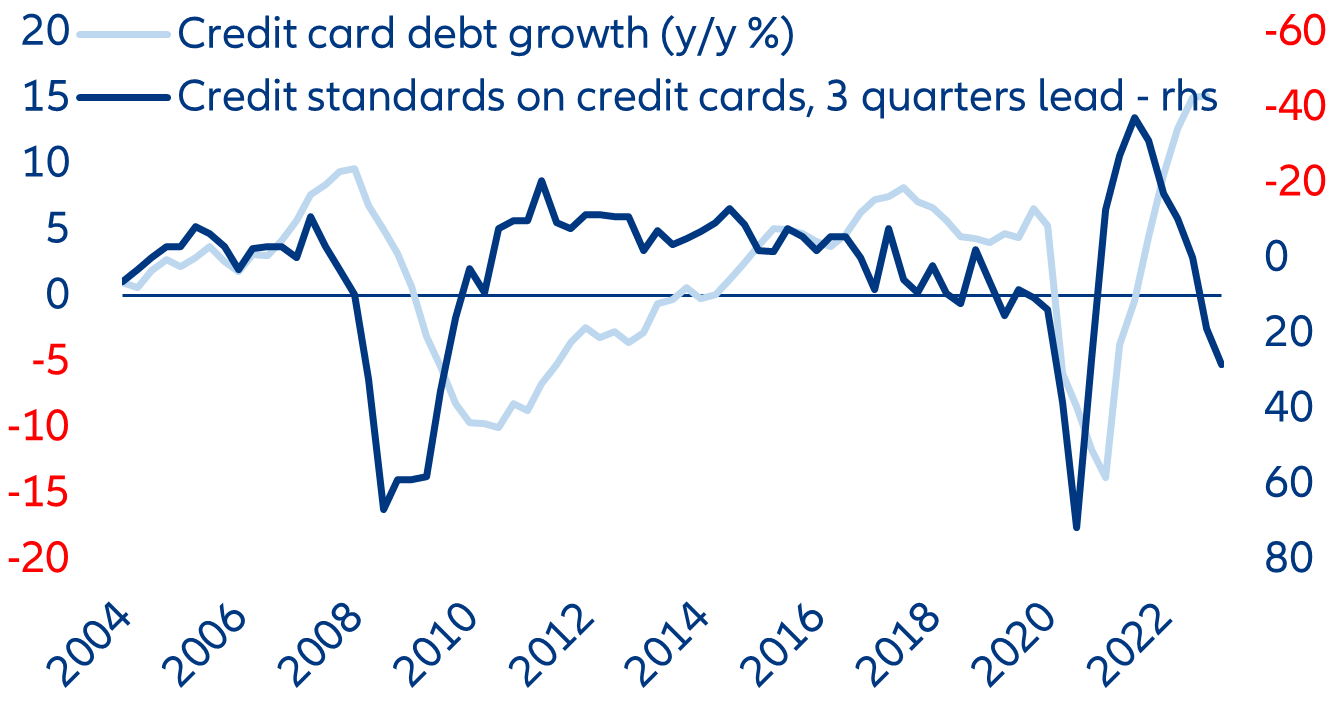

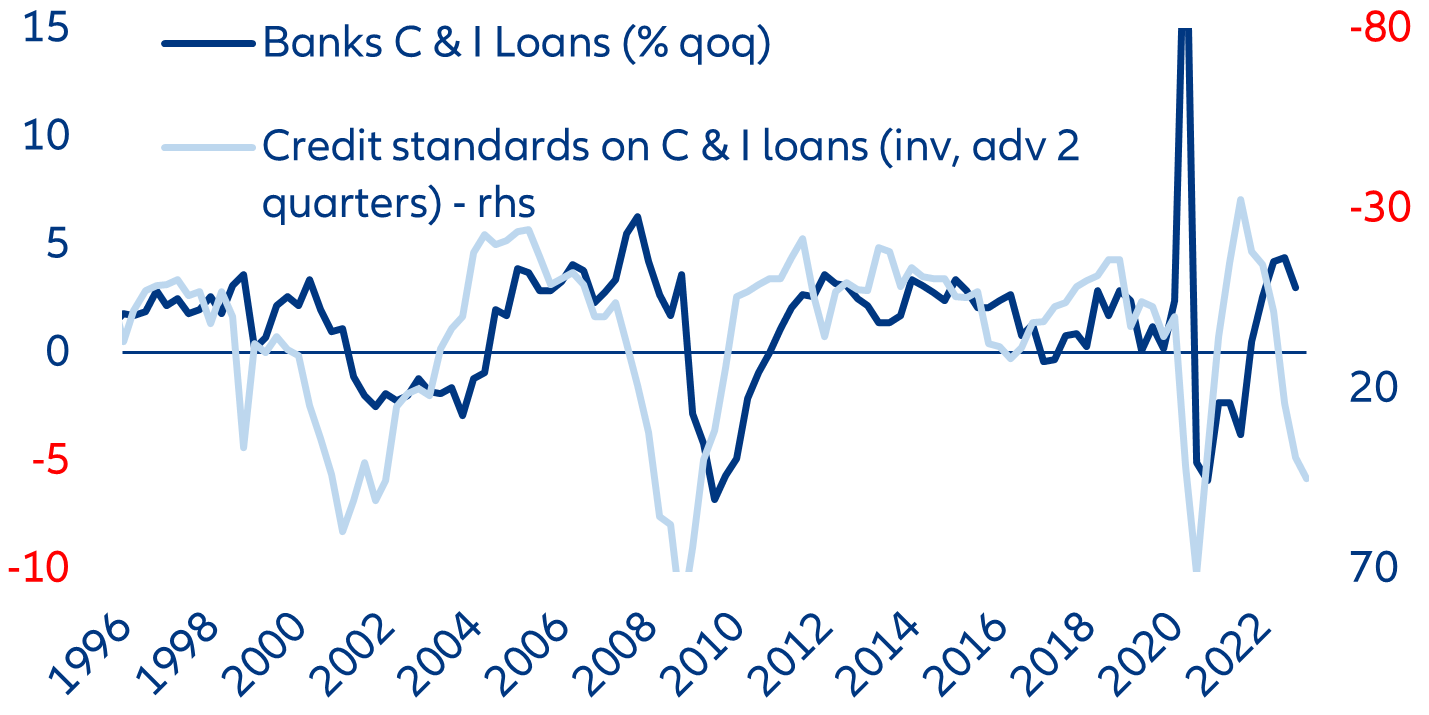

Looking ahead, we expect a final 25bps hike in the May meeting, followed by cumulative 75bps rate cuts in November/December. Chairman Powell stressed multiple times that the banking turmoil will likely accelerate the tightening of lending standards[2], stating that tighter banks standards are equivalent to ‘rate hikes’. In other words, tighter credit standards will do the heavy lifting to squeeze aggregate demand and bring inflation back down, relieving the pressure on the Fed to increase interest rates further. The latest Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey, conducted in Q4 2022, already showed a marked tightening of credit standards across all types of products, signaling drops in consumer credit and business investment before the end of the year (Figure 1).

France – major political and social crisis could push economy into recession

French President Macron is facing a major political and social crisis after pushing through a controversial pension reform. Fearing that it would not get a majority in the National Assembly, the government opted to trigger Article 49.3 of the Constitution, which allows bills to be passed without a vote. Opposition parties subsequently submitted two no-confidence motions, one of which fell short of taking down the government by only nine votes. In response, protests and violent riots are breaking out across the country.

The tensions and anger go well beyond the rejection of the pension reform. They reflect a growing dissatisfaction – exacerbated by the current cost-of-living crisis – with the political class, a malfunctioning welfare state and heavy taxes. Mistrust in political representatives has been steadily growing since the 2005 referendum when the government (under the Presidency of Nicolas Sarkozy) pushed the European constitution bill (rebranded ‘Lisbon Treaty’) through Parliament two years later, even though it was rejected by the popular vote. Not a single referendum has been held since then. More recently, the repeat of the standoff between Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron in the 2022 Presidential elections angered part of the electorate. Many were also frustrated by the perceived absence of political debate during both the 2017 and 2022 presidential campaigns (in 2017 because of a political-financial scandal engulfing the right-wing contender François Fillon and in 2022 because of the war in Ukraine).

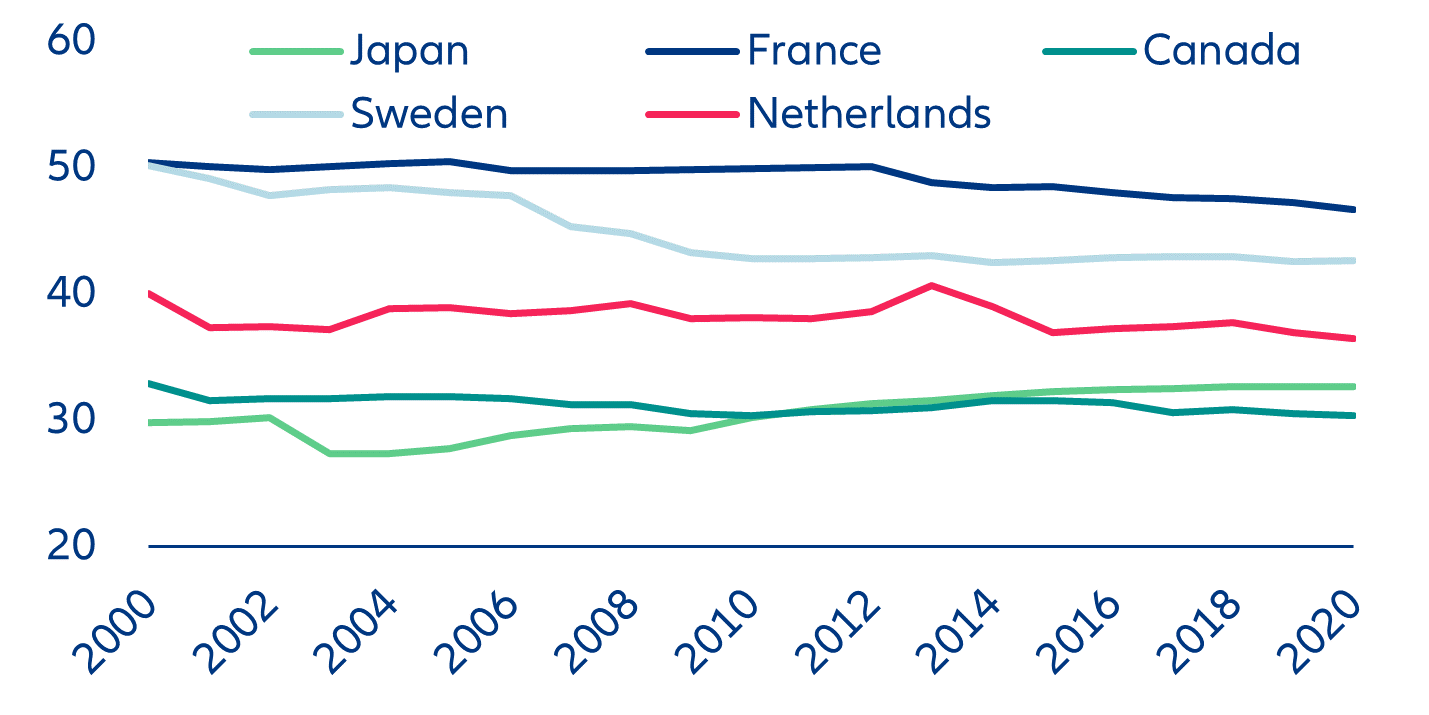

Economic factors have also greatly contributed to rising social and political tensions in France. Despite being one of the top spenders in advanced economies (public spending represents around 56% of GDP), there is a widespread perception among the people that the French state spends more and more inefficiently even as the tax burden remains elevated. The quality of basic public services (hospitals, schools, the judicial system etc.) is deteriorating fast.

To fund large expenditures, the French state taxes households and corporates heavily (which still leaves substantial public deficits to fund the remaining shortfall). French workers face one of the highest tax wedges (i.e. the difference between gross before-tax salaries and take-home pay, Figure 2) in OECD countries. This is fuelling the backlash against working longer (the aim of the pension reform). The Yellow Vest protests in 2018 were initially triggered by the government’s plan to increase fuel taxes, adding further pressure to household incomes.

Macron’s second term is turning into a lame-duck presidency: Major structural reforms are unlikely to be pushed through until 2027 and we expect the government to focus on reducing public deficits through discretionary spending cuts and tax hikes. Since the constitutional revision of 2008, the usage of article 49.3 is limited to one bill per parliamentary session. The right-wing party Les Républicains (LR) will be less likely to back certain reforms, given the unpopularity of the government: several LR MPs voted for the no-confidence motion, going against the LR leadership. If President Macron decided to call for new general elections, the Parliament would likely become even more fractured. In this context of political gridlock, major structural reforms are unlikely. Instead, the government will strive to reduce large public deficits to comply with EU fiscal rules and assuage financial markets. President Macron announced a new levy on ‘super profits’ while Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire announced significant spending cuts for 2024. We expect the public deficit to narrow to -4.9% of GDP next year, from -5.5% this year.

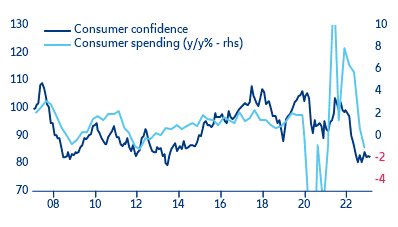

In a scenario where social tensions escalate, the hit to the economy could reach 0.5pp of annual GDP in 2023-24, tipping it into recession. We expect French GDP to flirt with recession, growing by a lacklustre +0.4% this year and +0.8% in 2024. The pass-through of high spot gas and electricity prices to corporate retail bills, elevated inflation and the ECB-induced tightening of financial conditions are increasingly weighing on the economy. If social tensions escalate in the coming weeks (40% probability) we think the economic impact would be felt primarily through depressed consumer confidence and reduced consumer spending (Figure 3). Using a simple statistical model, we estimate that a fall in consumer confidence in Q2 to Q4 2023 of roughly the size seen during the Yellow Vest protests in 2018 would knock consumption by up to 0.5pp annualized in early 2024 (accounting for lagged effects), or 0.3pp of GDP. However, we would also expect disruptions to industrial production and shortages of petroleum products (and a further dent to consumer confidence), which would probably push the GDP hit up to at least 0.5pp, in our view. Effectively, we could see several consecutive quarters of negative growth in the second half of 2023.

EU electricity markets – If it ain’t broke don’t fix it

The core of the Commission's proposal lies in the addition of long-term instruments that not only provide all electricity consumers – including private households – with a higher degree of (price) stability but above all are intended to set the right incentives to push sustainable investments in electricity generation and consumption. Two instruments are involved: PPAs (power purchasing agreements) and CfDs (contracts for difference). The former are bilateral contracts between power producers and consumers, which have so far been used mainly in industry, providing large-scale consumers with long-term certainty about prices and volumes. The idea is to open these advantages to retail users (private households and small and mid-sized corporates) as well. CfDs, on the other hand, are concluded between the regulator and electricity suppliers and lead to compensation payments if the electricity price falls outside a defined band. Symmetry is now supposed to prevail: If prices are too high, the electricity producer has to pay – in this way, the problem of ‘excess profits’ (and their possible skimming off) is solved elegantly at the same time. The main goal of the CfD, however, is to create a long-term stable calculation basis for investments in renewables. The planned regulation is associated with a variety of accompanying measures to increase the acceptance and dissemination of these instruments. Ultimately, however, it is up to the market participants to decide if they make use of them.

The European Commission's proposal takes into account the fragility of a pan-European electricity market with major regional differences. It is a reform with a sense of proportion that improves the status quo – especially if it succeeds in significantly increasing the use of CfDs and thus investment. In this context, not only power generation but also increasingly the grid infrastructure must be taken into account: Investments in digitization for smart control of electricity consumption and sufficient storage capacities are urgently needed to provide the necessary flexibility to supply and demand. For example, ‘energy prosumers’ will be supported in sharing their self-generated electricity as member states are required to adapt the grid so that electricity can also flow ‘the other way around’ from consumers into the system, and put the appropriate IT infrastructure in place. Transmission-system operators are encouraged to procure ‘peak shaving’ products, which allow the reduction of electricity demand during peak hours. The flexibility needs of the electricity system will be periodically assessed and appropriate support schemes should ensure the availability of sufficient capacity of the demand-side response and storage. This is necessary for renewables to reduce the price of electricity in Europe in the long run, and thus secure the competitiveness of Europe’s industry.

More than the energy market itself, the reactions of governments to the energy-price crisis need reform. Uncoordinated and poorly targeted market interventions create the wrong incentives for all market participants. This even applies to the German electricity-price brake, which at least on paper provides incentives to save energy. In the current market situation, fixed prices are more likely to keep prices higher for longer by undermining the willingness to switch – the most effective element of competition in the electricity market. The German electricity-price brake exemplifies the delayed and over-engineered interventions in a complex market. Even if the extreme swings of last summer are unlikely to be repeated in this form, the next energy-price crisis is bound to come and governments should be well prepared. To do so, they need a toolbox of effective and targeted measures ex ante that will bring rapid relief to those really affected, such as lump-sum payments to needy households.

In focus – Swiss shotgun wedding: what’s next?

Switzerland’s government is putting a lot of taxpayer money at risk. The agreement comes with a continued liquidity facility from the Swiss National Bank (SNB) for CHF100bn and a backstop for losses up to CHF9bn if UBS suffers losses from selling off hard-to-value assets on Credit Suisse’s books in excess of CHF5bn. This could be taken to imply that there is a problem of solvency and not just liquidity. The purchase price equates to ~4% of book value, and about 10% of Credit Suisse’s market value at the start of the year. This suggests that a substantial part of Credit Suisse’s USD575bn assets may be either impaired or perceived as being at risk of becoming impaired.

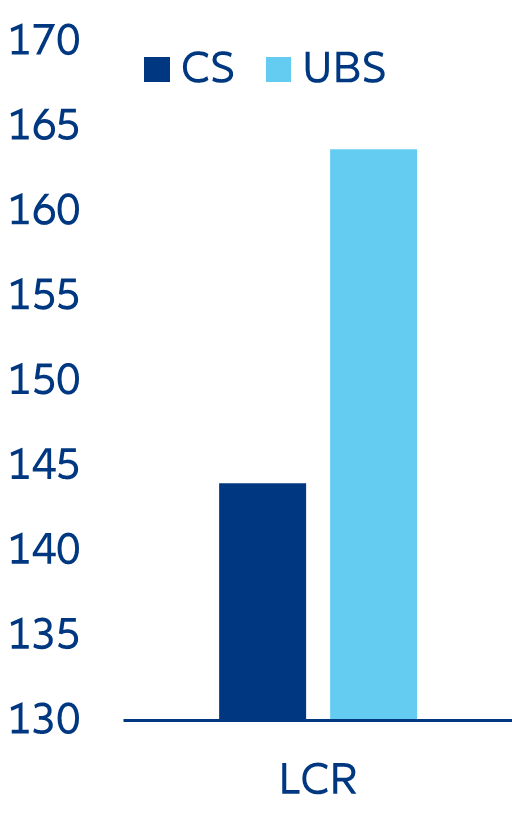

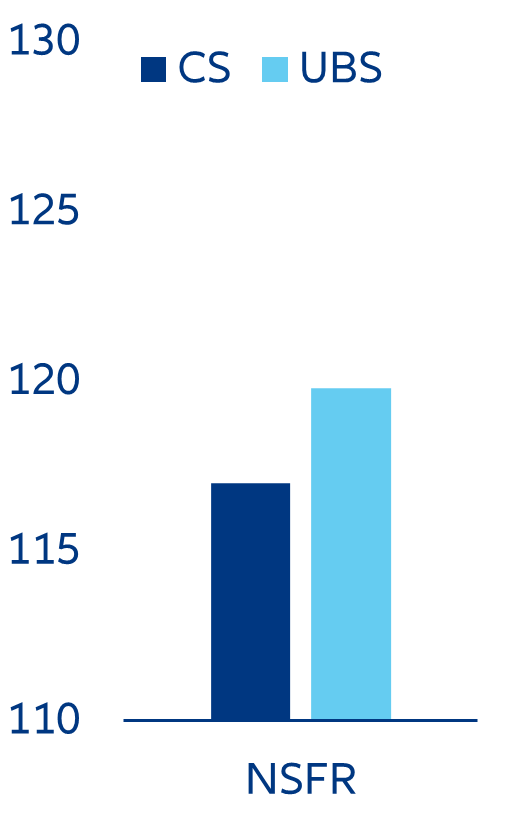

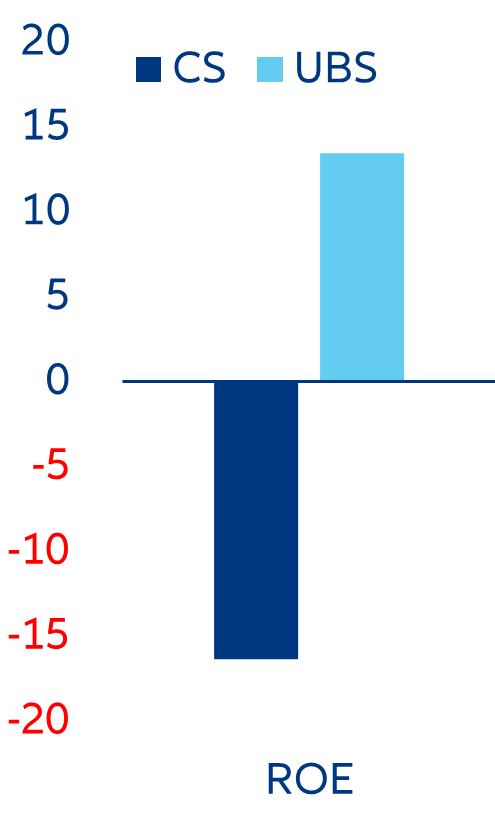

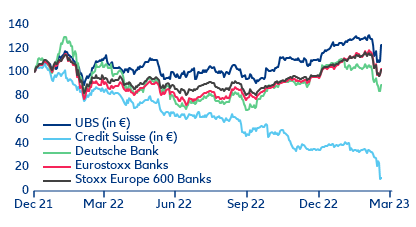

The deal also carries substantial legacy risks for UBS. Credit Suisse has substantial off-balance-sheet exposures and is still nursing wounds from several scandals (including Archegos, Greensil and Credito Real) that cost the bank a combined USD7.3bn. At the end of last year, the bank had already suffered a sharp drop in deposits and net assets outflows (8% of total AUM only in Q4 2022, 15% in the wealth management division), which decreased its liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) from 192% to 144% and its net stable funding ratio (NSFR) from 136% to 117% at end-2022. Continued attempts to recapitalize the bank were not enough: The group completed two capital increases in November and December. The last annual report had already identified material weaknesses on financial reporting and even though the Swiss Central Bank offered a USD54bn lifeline, it was ultimately not enough to ease the widespread doubts over the bank, which ultimately led to the regulator-pushed merge.

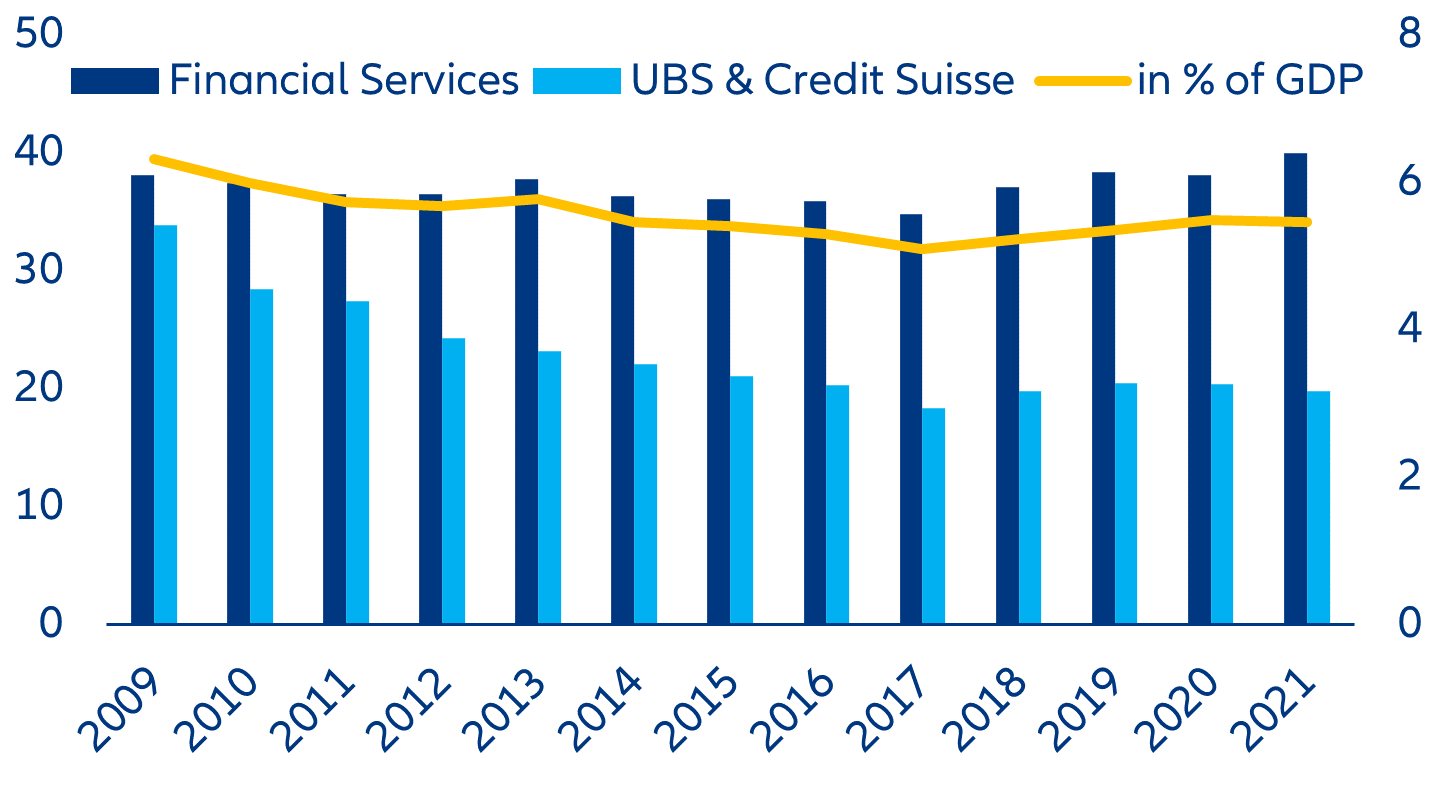

UBS’s takeover of Credit Suisse will have negative implications for the contribution of the financial services industry to the Swiss economy. In 2021, financial services contributed CHF40.1bn to Swiss GDP, of which about 50% was attributable to Credit Suisse and UBS alone (Figure 6). Even though the merged bank is bound to become one of Europe’s largest banks, staff layoffs and cutbacks in Credit Suisse’s investment and wealth management businesses will reduce combined revenues to less than the sum of both banks. Thus, we expect an accelerated decline of the banks’ relative contribution to Swiss GDP, which already declined from 6.3% in 2009 to 5.5% in 2021, and stood at 5.2% at the end of 2022.

We see no spillover effects from the write-down of Credit Suisse’s hybrid capital

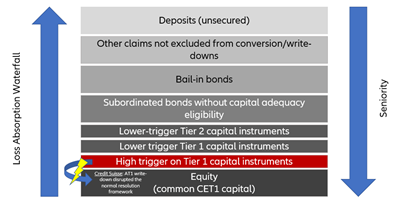

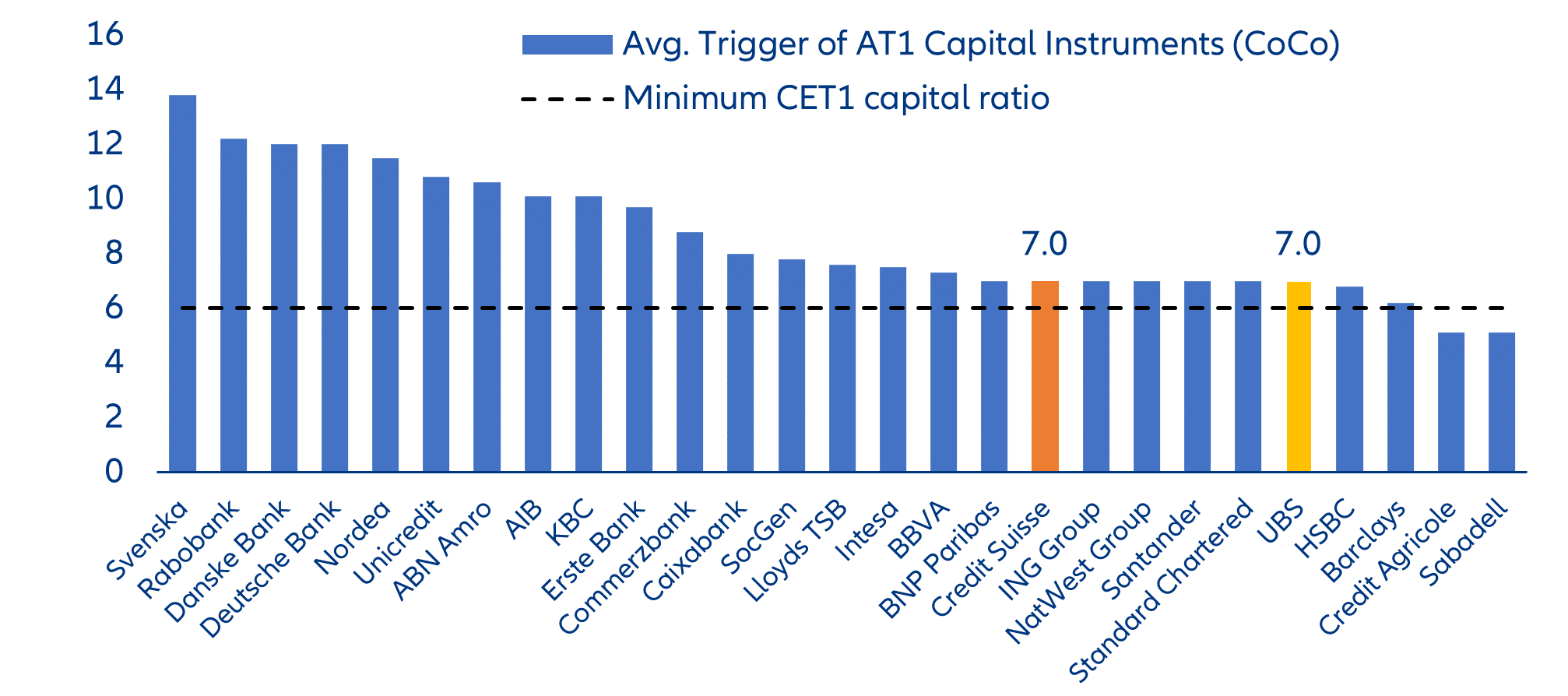

The complete loss of hybrid capital in Credit Suisse was unusual but legal. As a precondition for the emergency liquidity support from the SNB, Credit Suisse had to ensure its continued viability, which was only possible by writing down all its outstanding subordinated additional Tier 1 (AT1) capital instruments, so-called contingent convertible bonds (or “CoCos” for short). Hence, Credit Suisse’s roughly USD17.3bn of these risky notes are now worthless, while shareholders (which normally rank junior as claimants) still receive some stock in UBS (albeit at a premium) – contrary to the conventional bail-in hierarchy of banks’ capital structure (Figure 7). The write-down could thus adversely affect this specific asset class (which amounts to USD270bn in Europe), particularly if other banks’ CoCos and high CET1 trigger levels should get into trouble (Figure 8). However, the permanent write-down of such hybrid capital instruments is specific to the two large Swiss banks (Table 1); all other large European banks have issued CoCos that make the write-down temporary (or covert into equity). Furthermore, we believe that the capital increase in late 2022 (CHF4bn) – almost half of it subscribed by the Saudi National Bank – weighed on the regulator decision as shareholders had already invested additional money or diluted their participations in an attempt to save the company before the takeover.

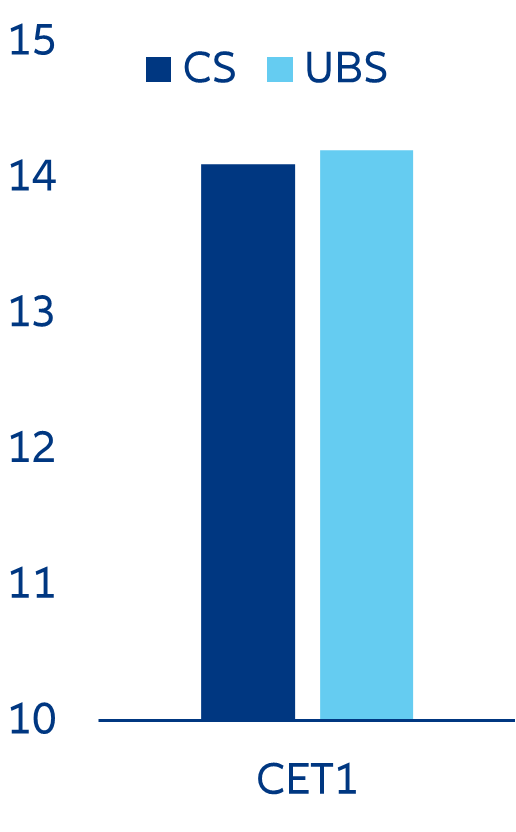

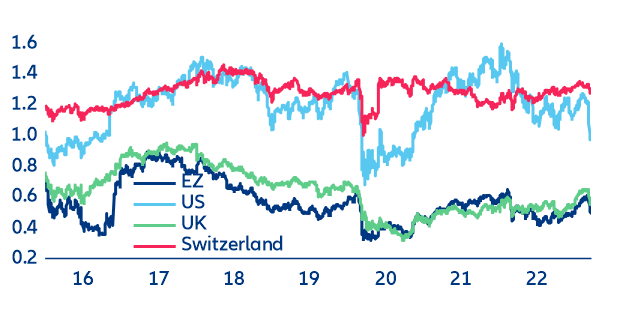

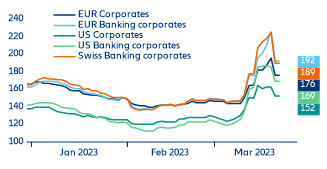

European banks seem well-shielded but funding and capital costs will probably increase, leading to a market repricing and readjustment. The health of the European banking sector has significantly improved over the last decade, mitigating potential spillover effects of Credit Suisse’s rescue. Larger European banks are even more liquid than their US and Swiss peers, holding more than EUR3trn in excess liquidity, together with a still-high share of unencumbered assets that could be used for accessing central bank money if funding stresses arise. However, there could be some small/individual liquidity-constrained banks. With a focus on the largest Eurozone banks (with total assets amounting to 80% of the region’s GDP), we find that the sector is in much better shape today than it was in 2015, thanks to better and more consistent regulation and supervision. Non-performing loans (NPLs) declined to less than 3% of the loan book (down from more than 7%) while the average common equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio has increased by more than 2pps. Liquidity also improved, with the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) rising from 125% in 2015 to 150% in 2022, way above the regulatory minimum of 100%.

For now, it appears that there is no “next Credit Suisse” in Europe. For several months, Credit Suisse had diverged from the rest of the banking sector in the continent, making it the most vulnerable to the disruption that occurred in the US regional banking sector two weeks ago. As a result, it is unlikely that we will see a significant and structural rise in systemic risk for the European banking sector soon. At the very least, if things take a turn for the worse, European policymakers will have a bit more time to respond than their US counterparts (Figures 9-11 ).

Central banks will moderate their restrictive monetary stance but hope that more conservative bank lending will help them out in reining in inflation

Financial stability concerns will influence but not condition the policy rate path going forward. Banking sector tremors have already tightened global financing conditions—but not fast enough for central banks to abandon their restrictive stance lest they risk inflation expectations becoming de-anchored. Thus, central banks’ first response to financial market stress is to provide ample liquidity to reconcile monetary policy and financial stability objectives. The preferred option seems to be moderating the restrictive stance and waiting for inflation to slowly decrease on the back of the lagged effects of monetary policy, without causing dislocations in capital markets. Both the ECB and the SNB hiked policy rates by 50bps despite financial-stability concerns last week.

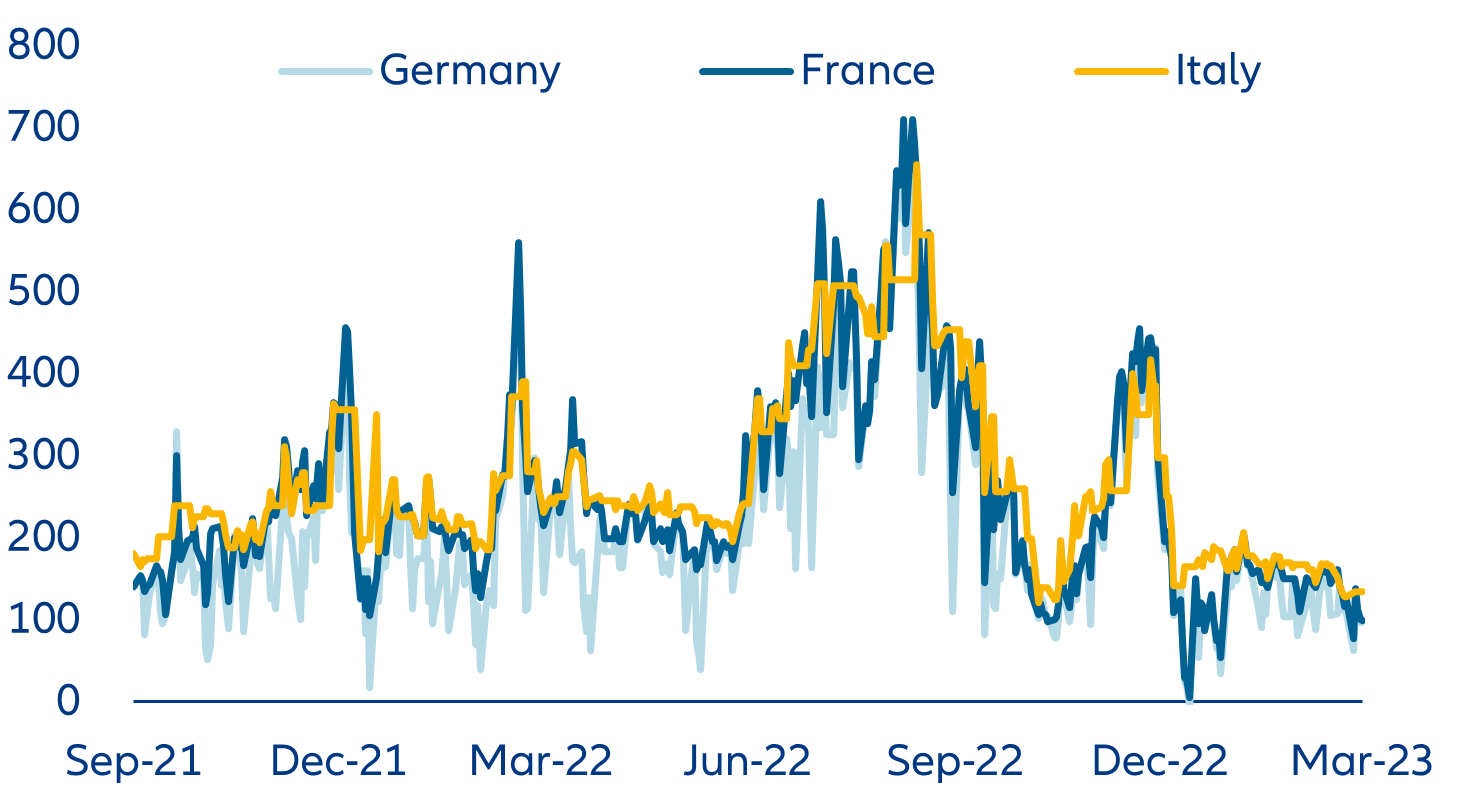

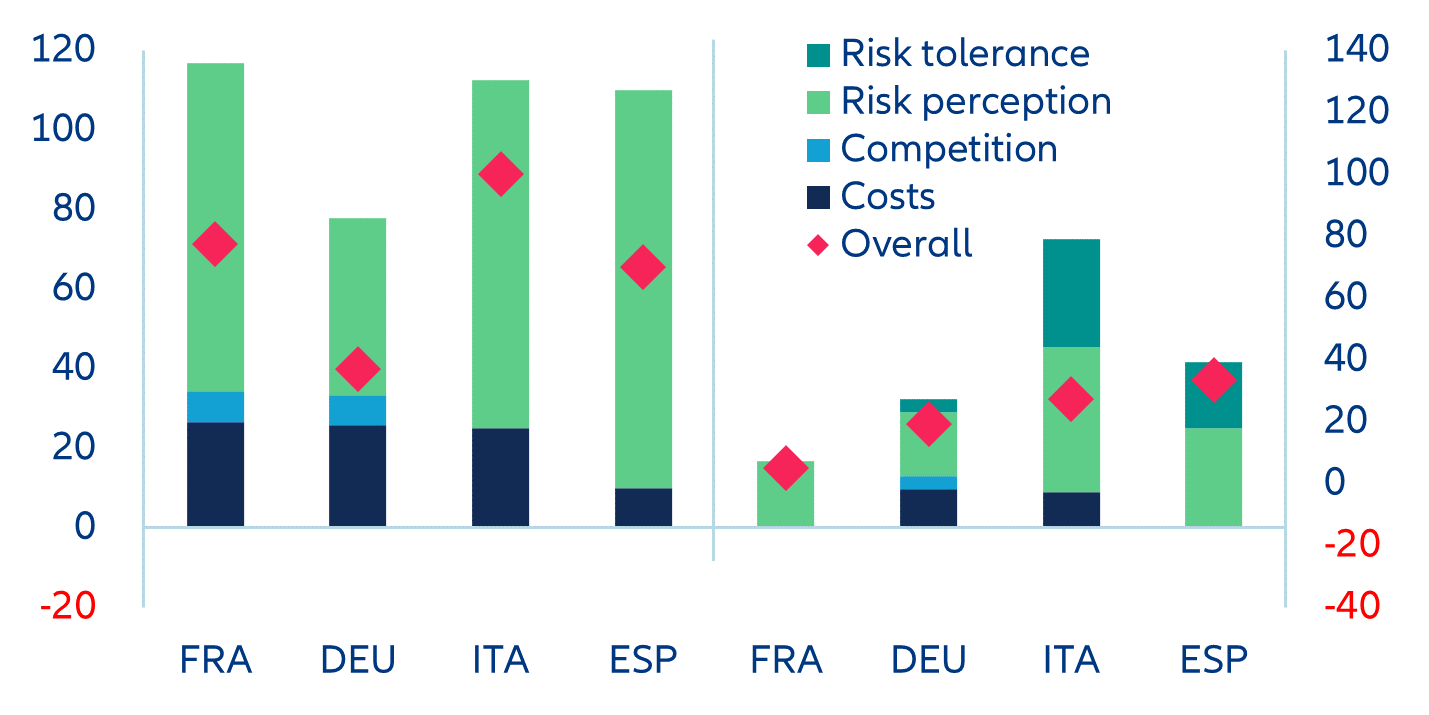

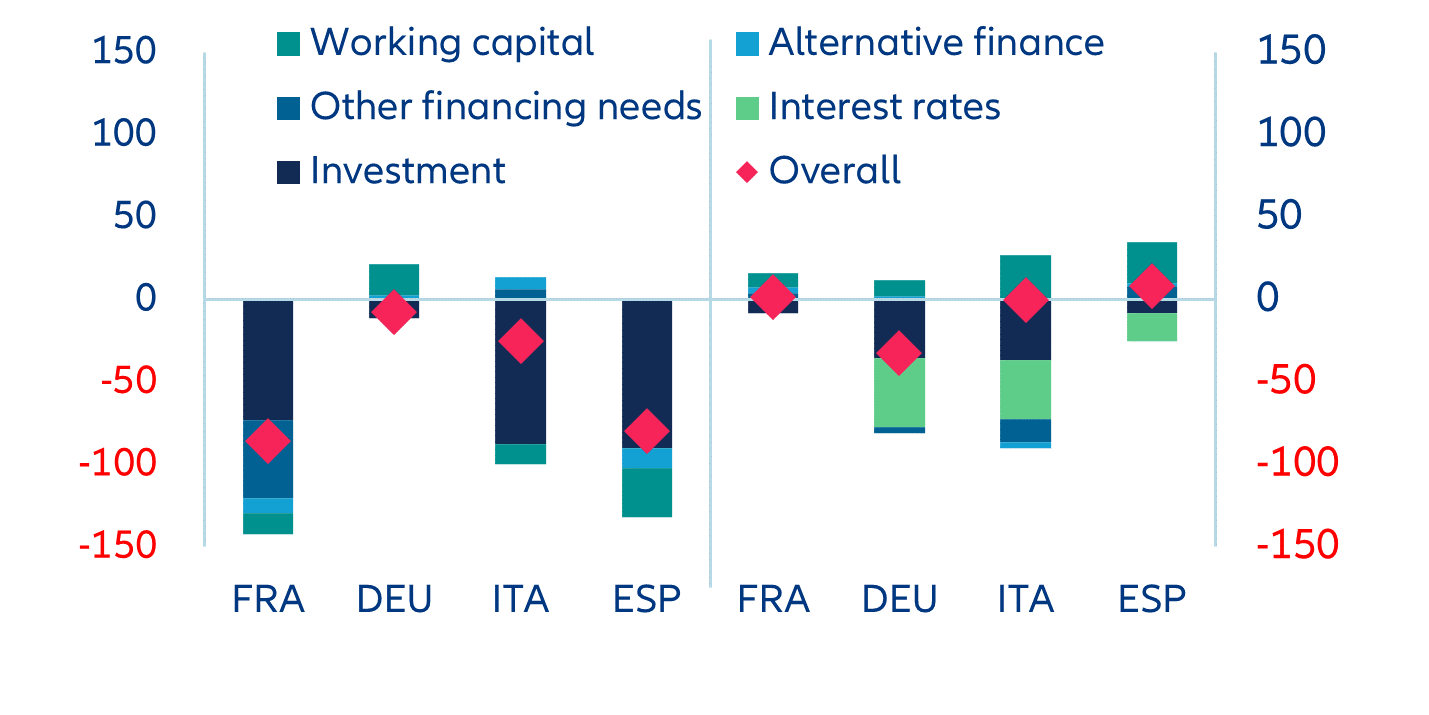

Deteriorating money and credit dynamics are already suggesting that the ECB’s policy hikes are having real bite, with potentially more pain potentially ahead. We expect annual growth of money supply and loans to the private sector in the Eurozone (to be published on Monday) to have decelerated further in February. Protracted uncertainty denting investment decisions and higher interest rates clearly impacted firms’ and households’ borrowing. The latest ECB Banking Lending Survey already confirmed that the decline in net demand for both housing and corporate loans will persist (Figure 12). In parallel, credit conditions have tightened significantly. We expect the CS-UBS episode to exacerbate the recent trends and banks to tighten significantly their lending criteria.

Insurers are affected by the interest-rate implications of the current market volatility rather than direct exposures to banks

A major difference between insurers and banks is their resilient funding via premium income. Insurers could see their liquidity deteriorate due to policy surrenders and lapses but cannot suffer deposit runs to the same degree as banks. Insurers are also much less likely to have to conduct a fire sale of underwater assets. The risk of an increase in life surrenders should not be overdone as a review of product literature reveals that there are significant penalties for early redemption. More broadly, there is considerable resilience with respect to asset risk, given the investment-grade weight of insurers’ asset exposure. Insurers own very little bank AT1, given onerous regulatory capital treatment. The vast majority (~90%) of financial exposure is to senior debt.

In general, insurers mainly worry most about the current uncertainty about the level and future direction of interest rates, alongside high levels of volatility. Given the lower downside solvency sensitivity to interest rates, reinvestment rates would have to fall a long way (>100bps) for the investment-income tailwind to earnings to be materially damaged. However, the current accounting transition to IFRS 17 and 9 is not ideally timed, and the impact of capital market volatility on the new regime is hard to tell. The accounting transition will generate better insight into the stock (and stability) of life cash flows and a more accurate reflection of the economic impact of interest rate levels on both assets and liabilities (a timely reminder of matching).

Markets will now have to balance the reduction of systemic risk with the likely higher financing costs and tighter lending conditions

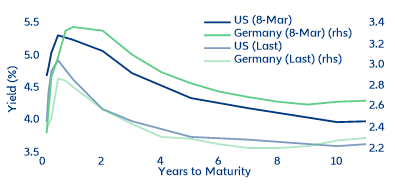

Going forward, the rescue of Credit Suisse has certainly elevated concerns about the health of the global banking sector and raised the risk of adverse spillover effects, resulting in a higher cost of capital for banks and non-financial corporates alike. Currently, markets do not seem overly concerned, but less resilient banks may face challenges in the future. Overall, we anticipate markets to remain turbulent, with all asset categories experiencing relatively high volatility in the short term due to mounting market and economic uncertainty. Following the initial sell-off and rush to safe-haven assets last week, markets are now triaging the banking sector into safe and risky names while figuring out how the current stress on banks will impact central banks' policy stance and the economic outlook. The prevailing ambiguity on the policy rate path in the US and Europe will result in increased market volatility over the near term. The downward adjustment in current sovereign yield curves suggest that central banks will stop hiking sooner than initially predicted, and that a more severe recession is imminent. We believe that the fundamental value for the long-end of the curve lies somewhere between the most hawkish point reached in the first week of March and the most dovish point reached in the past week. But we also acknowledge that short-term volatility will continue to prevent a smooth anchoring of both the short and long ends of the curves (Figure 13).

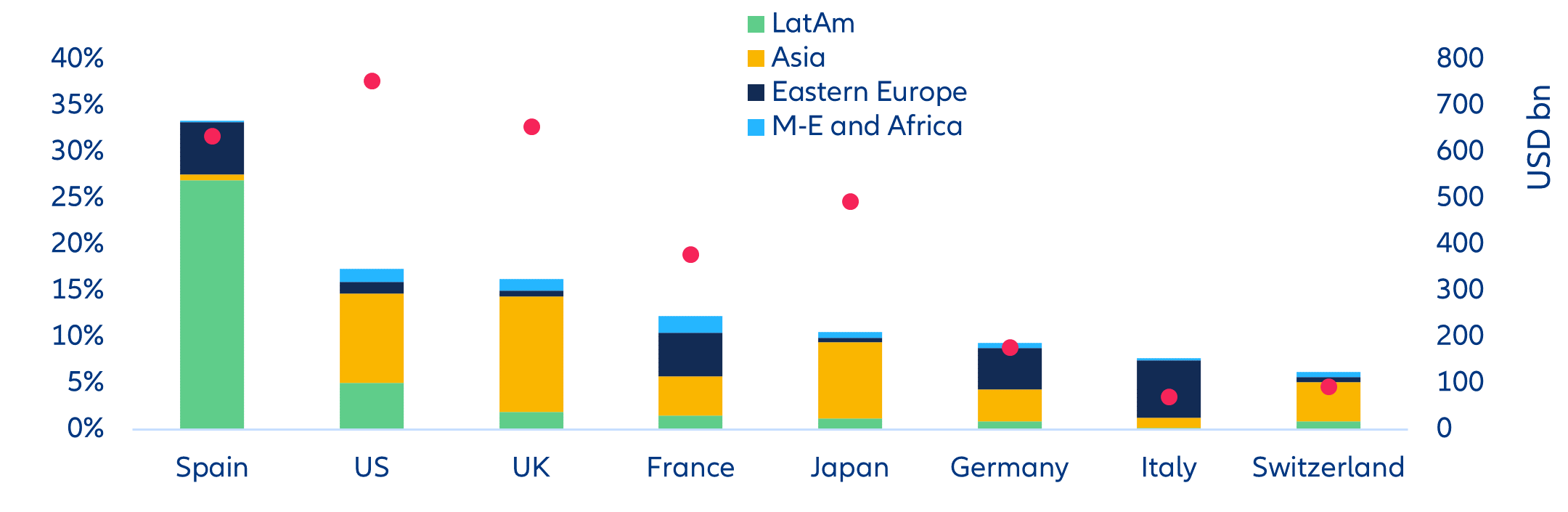

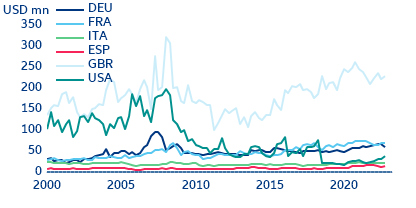

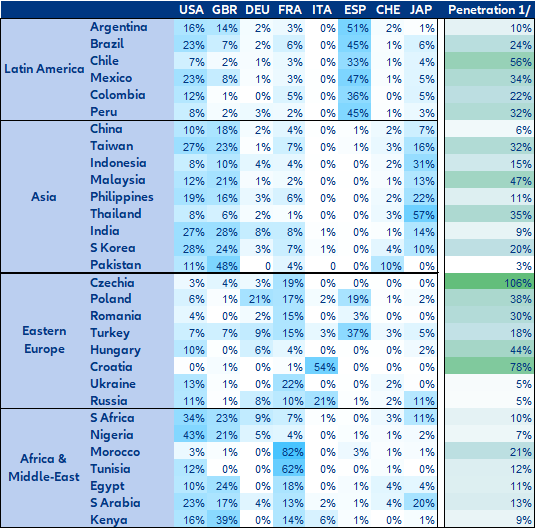

Limited spillovers to emerging markets

The financial sector in advanced economies (AEs) plays an important role in emerging markets (EMs), not only via investments but also through direct participation in the local banking sector. We find that Swiss banks are not significant in local banking sectors in EM countries, which limits the potential of direct spillover effects. In contrast, US and UK banks are certainly more relevant and could trigger adverse confidence effects if troubles in smaller US banks also affect larger peers (Figures 15 and 16; Table 2). However, current market volatility and the flight to safety still raise concerns about the risky-assets-repricing type of contagion for EMs.