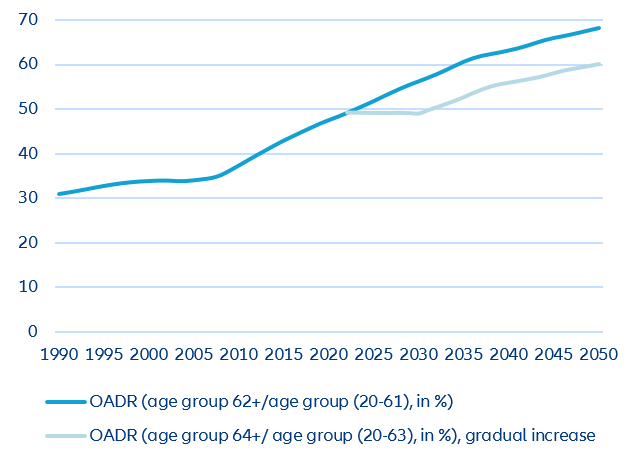

- The current reform proposal in France has been met with considerable anger, seen as the end of savoir vivre. But the truth is that the reform barely goes far enough. The proposed increase of the statutory early retirement age to 64 years from 62 does not address long-term deteriorating demographic and funding prospects: There will still be 60 persons in retirement (aged 64 and older) per every 100 people at working age (between 20 and 63 years) in 2050. Today, the ratio is 49.2%.

- The reform has other important shortcomings. Current pensioners will not be affected unlike current workers (and future pensioners) who are already being stretched by falling real wages. The ‘special regimes’, under which employees benefit from more generous schemes, will be scrapped very slowly since the new less generous terms will apply only to new hires.

- Without measures to adapt the working environment to the needs of an aging workforce, the reform might end up increasing unemployment in old age. Raising the retirement age could add up to 1.6mn people to the workforce in 2050, by when 22% of the workforce is set to be 55 and older. But given the prevailing ageism – with the unemployment rate for the age group 55-64 is 6.3% in France, more than twice as high as in Germany – efforts to integrate older workers must be doubled down.

- In Focus - Bonjour tristesse: Planned pension reform in France stirring up social tensions

- US inflation—past the peak and falling rapidly in the next six months, ending the year close to 2%.

- Yesterday’s data release provided further evidence that US inflation is firmly on its way down.

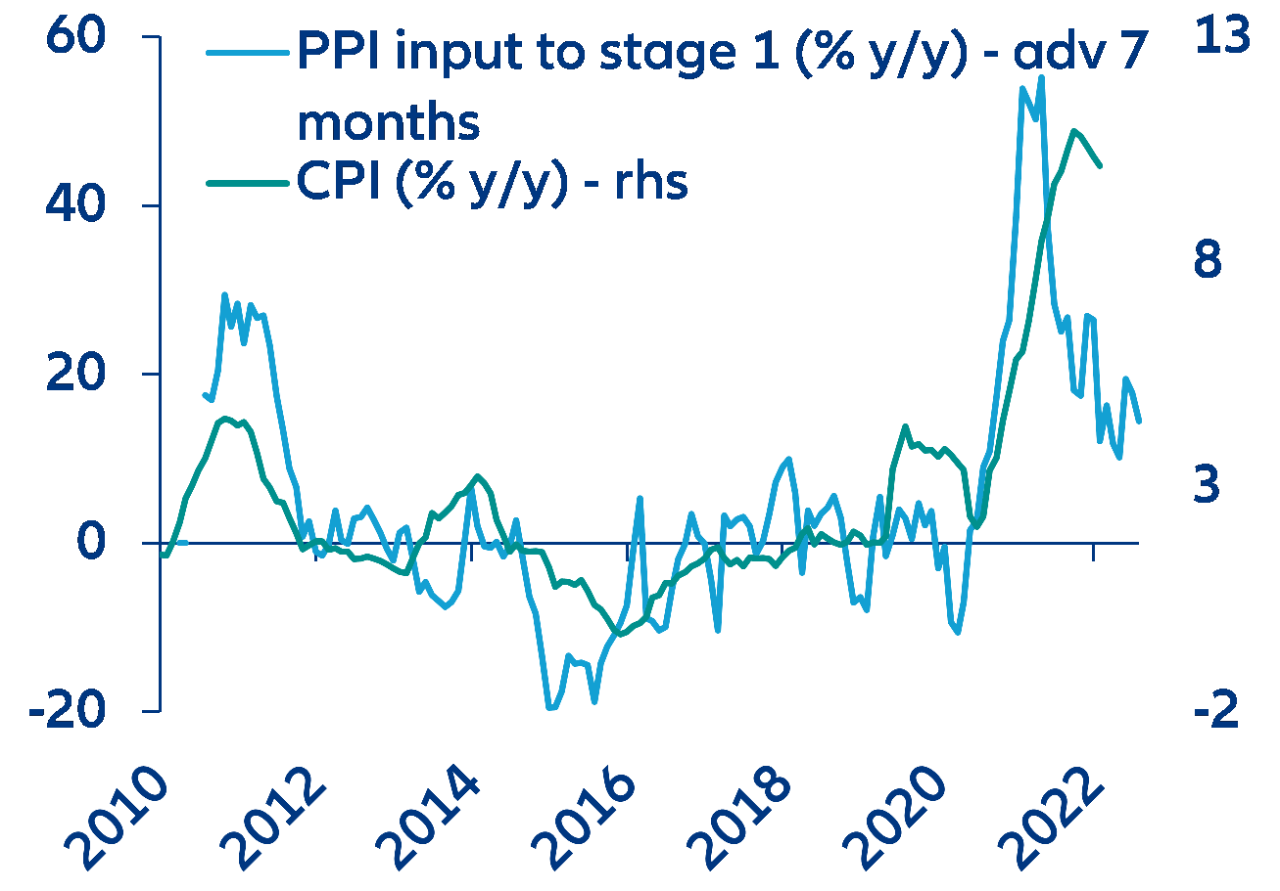

The December CPI printed at 6.5% y/y, pulled down by sharply lower energy inflation; on a sequential m/m basis, prices dropped by -0.3% – the biggest drop since April 2020 at the height of the pandemic. Looking ahead, we expect CPI inflation to continue to come down in the coming months. Energy inflation should turn negative by next April or May. Food inflation is elevated, but upstream price pressures in the food industry are easing rapidly and suggest more than a halving of food inflation by mid-year (see Figure 1). Finally, the easing of supply-chain disruptions – compounded by faltering economic momentum – will continue to pull down core goods inflation.

Figure 1. US food inflation

Sources: Refinitiv, Allianz Research

- While rapidly easing US headline inflation in the next few months is baked into the cake, there is much more uncertainty for the end of 2023 – and beyond. The NFIB survey of businesses’ salary plans suggests that wage growth will not fall much below 5% before the end of the summer – a level clearly inconsistent with underlying inflation sustainability at 2%.

- However, we think the evolution of aggregate demand vs aggregate supply – what determines inflation in the medium-term – will push inflation down close to 2% by Q4 2023. Aggregate demand is expected to fall in 2023 (-0.3% GDP drop), while the recovery should remain quite subdued in 2024. The Fed is committed to keeping rates high for long. Its powerful channel of influence on inflation is through property prices, which lead rent inflation by roughly 12 months. Property prices are set to decline more than -10% peak-to-trough, as we have shown in an earlier publication. On the fiscal front, the federal government is unlikely to loosen the purse strings amid political infighting in Congress. State governments face deteriorating public finances prospects and will likely embark on tightening before long. Meanwhile, on the supply side, the US economy seems to have withstood the pandemic shock relatively well, albeit with lower labor force participation. The combination of weak demand and resilient supply means that inflation will move back to close to 2% in a context of anchored medium-term inflation expectations.

- Eurozone inflation—sharp drop, thanks to energy subsidies, but sticky core inflation this year

- In December, Eurozone headline inflation fell for the first time since the beginning of 2021 to 9.2 % y/y, down from 10.1% during the previous month. A key driver was the declining contribution of energy prices, especially in Germany, where inflation slowed to 8.6% y/y (not seasonally adjusted), thanks in large part to government gas and heating subsidies. This brings annual inflation to less than 8% y/y (and below our initial forecast of average inflation of 8.5% in our last economic outlook in December. However, inflation dynamics remain strong, especially for services. In addition, Inflation may well rise again in January since the German measures were a one-off. Nonetheless, inflation will remain uncomfortably high during this quarter before falling from Q2 onwards, when the German gas and electricity price caps kick in.

- Core inflation will likely stay at 4% until the end of the year due to continued (albeit abating) wage pressures. Survey measures of hiring intentions, including the employment component of the PMI, point to only a modest increase in the unemployment rate this year. In addition, the latest activity and sentiment data suggest a milder recession in H1 2023, with activity declining at a slower pace in the last month of 2022.

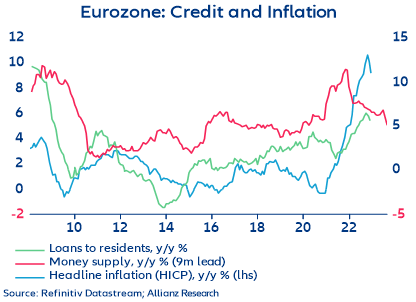

- Weaker nominal growth of monetary supply could become a more prominent driver of slowing inflation (Figure 2). Underlying credit growth, albeit weaking slightly m/m, remained positive, and banks are still lending to corporates and households at a healthy rate. Real M1 in November fell further below zero to-7.7% y/y from -6.8% in October, the lowest since records began in 2001. The underlying message remained more positive, with the credit growth to non-financial corporates, which remained strong at 7.3% in November, slightly lower than the 8.1% in October. Loans to households adjusted at a more modest pace to 3.9%, down from 4.1% a month earlier.

- Strong core inflation and economic surprises will make it easier for the ECB to maintain a hawkish stance, suggesting further euro appreciation. Energy concerns that loomed large as a euro-negative in mid-2022 are beginning to ebb. The structural resilience of labor markets will delay a pivot in monetary policy until next year and keep financing conditions tighter for longer. The ECB has made it clear that its big fear is entrenched inflation, which is more likely to be reflected in rising core inflation.

Figure 2 – Eurozone: credit, inflation and money growth

Sources: Refinitiv, Allianz Research

- China—bumpy reopening but overall net positive for global growth this year

- China has shifted away from zero-Covid very quickly; difficult winter months lie ahead before an economic rebound from Q2. Since December 2022, sanitary restrictions have been lifted rapidly. That has led to uncontrolled outbreaks across the country, with mobility averaging -16% y/y in December, i.e. the worst monthly performance since March 2020. While the most recent data suggest a potential peaking of outbreaks in the bigger cities, national mobility in the first ten days of January still averaged -8% y/y. This sanitary situation, along with the poor performance of leading indicators, confirms our expectation that the Chinese economy is starting 2023 on very shaky grounds. The Chinese New Year holidays later this month are likely to extend the period of weak economic activity as people travel to their hometowns for family celebrations (around 3bn trips estimated in pre-pandemic times), potentially carrying the virus nationwide. On top of that, weakening global demand and the continued slump in the property sector will continue to weigh before domestic demand rebounds on a post-Covid boost, most likely from Q2 2023. This is a little earlier than our previous expectation of H2 2023, meaning that risks to our 2023 growth forecast of +4.0% are skewed to the upside.

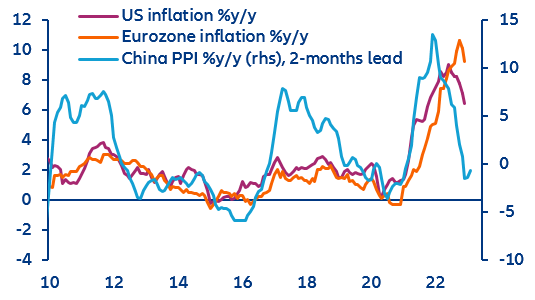

- Positive news for the rest of the world: the return of the Chinese consumer, with limited inflationary pressures. After initial (likely manageable) pressures on demand and supply chains due to the ongoing outbreaks, the post-Covid normalizing Chinese economy should prove beneficial for the rest of the world. All quarantine measures for inbound travelers were eased on 8 January, paving the way for a return of Chinese tourists abroad in 2023. The broader return of the Chinese consumer is likely to be less inflationary than the experience of many other countries through 2021-2022, given a more flexible labor market, a small share of services in the CPI basket and smaller excess savings. China’s reopening will further help ease supply-chain pressures, which had already been unravelling on the back of increased manufacturing capacity and weakening global demand. This could help drive down global inflationary pressures in a context where producer prices in China are already on a downward trend (Figure 2). From a capital market perspective, the first weeks of 2023 have been especially positive, with the Hang Seng index gaining more than +8% (larger in US-listed Chinese stocks) and the CSI 300 more than +3% (Figure 3).

Figure 3. China producer prices vs. US and Eurozone inflation

Sources: Refinitiv, Allianz Research

- After the winter break lull, expectations of a monetary policy pivot, especially for 2024, brought a dramatically positive start into the new year. On a year-to-date basis, 10y sovereign rates have fallen by ~30bps to 3.5% for the 10y UST and 2.2% for the 10y Bund. Risky assets, especially in the Eurozone, are having one of the best starts of the year in decades. In terms of equity markets, the S&P500 has risen by +3.5% ytd while the Euro Stoxx has rallied an historically impressive +7%. This has also translated into lower corporate credit risk, especially for high yield.

- However, given the uncertain economic outlook, the current market performance provides poor guidance for the overall 2023 market performance. The current market trend is likely to be rather fragile and is built on expectations rather than hard data. Following the motto “what policy gives, policy can take away”, markets’ expectation of a monetary-policy-pivot repricing due to higher recessionary pressures and declining inflation can still be challenged, especially during the first half of the year. This will most likely leave markets at the mercy of elevated volatility and will not shield investors from the possibility of a full-fledged market reversal. After the first 10 days into the year, most asset classes have already overshot our target 2023 market forecasts. However, we remain skeptical about the current market momentum as we expect recessionary pressures to continue challenging corporate and economic fundamentals.

In Focus: Planned pension reform in France stirring up social tensions...

- To ease the financial burden on the pension system, the French government plans to raise the statutory minimum retirement age by two years from 62 to 64 by 2030, and to bring the already agreed upon increase in the number of contribution years that are necessary to receive a full pension, from 41.5 to 43.0 years, forward from 2035 to 2027. The retirement age at which a full pension can be drawn regardless of the number of contribution years remains unchanged at 67.

- However, in an international comparison and given that retirees in France have one of the highest life expectancies worldwide, the reform steps seem rather modest. According to the latest CNAV data, in 2021, the average retirement age of a man in France was 62.7 years and that of a woman 63.2 years; it was 62 years and six months and 62 years and 11 months, respectively, for new AGIRC-ARRCO pensioners. Given the further life expectancy at the age of 63, that means the average French male retiree is set to spend 21.5 years in retirement while a female can expect to spend 25.4 years in retirement. For comparison, in Germany the average retirement age of a man was 64.1 years and that of a woman 64.2 years in 2021 and the average expected time spend in retirement was 18.6 years (men) and 22.1 years (women), respectively. In fact, France was the country with the highest share of public pensioners below the age of 65 of all public pensioners in the EU before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic: In France, 42% were younger than 65 compared to 14% in Germany and the EU average of 26%.

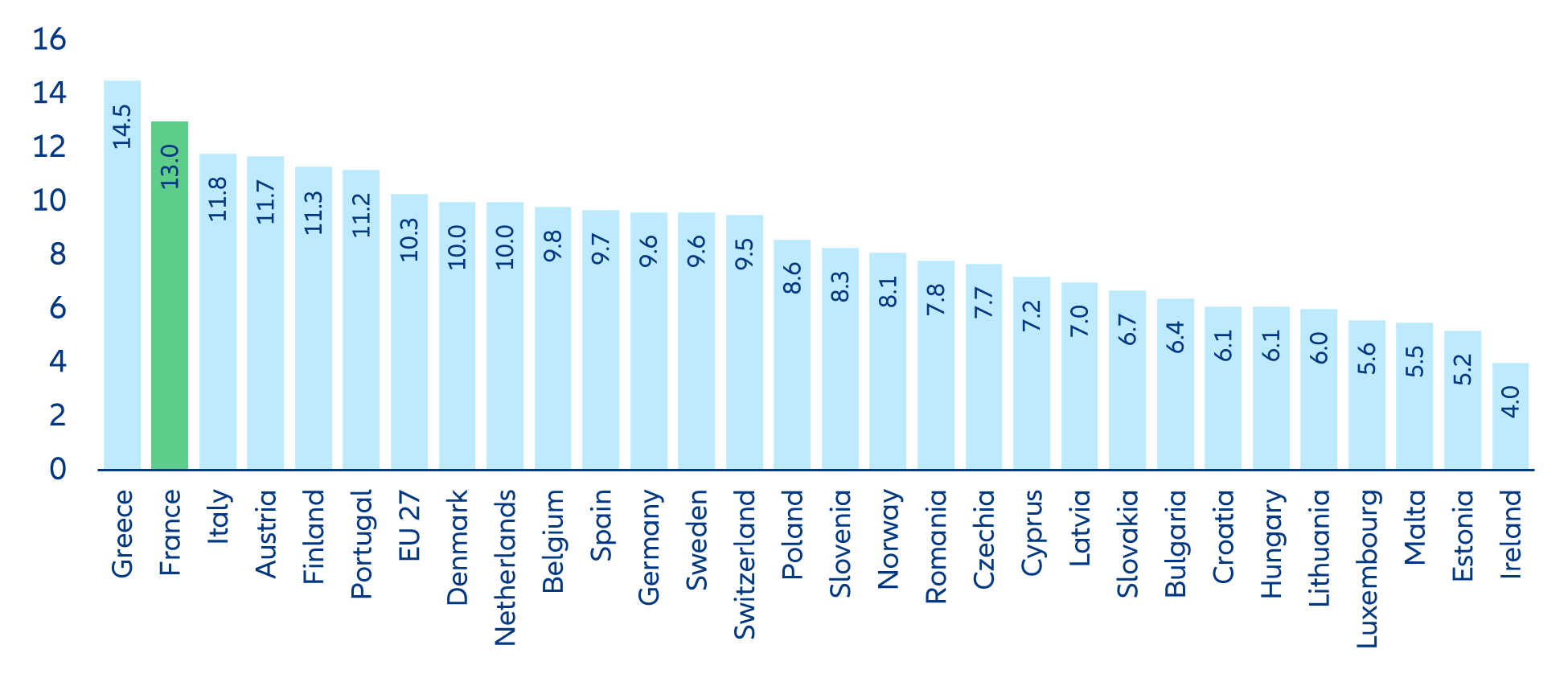

- Furthermore, France is also the country with the second-highest public spending for old-age pensions within the EU, behind Greece. In 2020, the expenditures for old age pensions amounted to 13.0% of GDP in France compared to 10.3% in the EU on average and 9.6% in Germany. Without changes in the retirement age, the EU Commission estimates that the share of public pensions would increase to 15.5% by 2050.

Figure 5: France among countries with highest pension spending in EU (2020)

Sources: Eurostat database and Allianz Research

- However, given the expected demographic development, the proposed reforms might not go far enough. Even with the planned increase of the statutory early retirement age, there are going to be 60 people aged 64 and older, i.e., in retirement age, per 100 persons in working age between 20 and 63 in 2050. To keep the old-age dependency ratio at today’s level (49.2%), the earliest statutory retirement age would have to be raised to 67 years by 2050 (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Higher old-age dependency ratio despite reform

Sources: UN Population Division (2022), Allianz Research

- Increasing the retirement age would also help cushion the impact of demographic change on the labor market: Without reforms, the number of people in working age between 20 and 61 is set to decline from 33.2mn today to 31.0mn in 2050. Raising the early retirement age to 64 would add 1.6mn to the labor force potential; 22% of the workforce population would be aged between 55 and 63 in 2050.

- However, the rise in the retirement age may also result in longer periods of unemployment before retirement. This is a real threat, given the fact that in France the unemployment rate in the age group 55 to 64 is well above the German and the EU 27 levels – 6.3% versus 3.0% and 5.5%, respectively – despite having much lower activity rates in this age group. In France, only 59.7% of the age group 55 to 64 were available on the labor market, compared to 74.1% in Germany and 64.0% in EU 27 in 2021. Therefore, the participation, employability and acceptance of older workers in the labor market must also be increased considerably. Otherwise, ageism might derail the well-intended reform measures.